Derek Abbott*

‘Brownout brutality in wartime Melbourne 1942’, Honest History, 26 June 2018

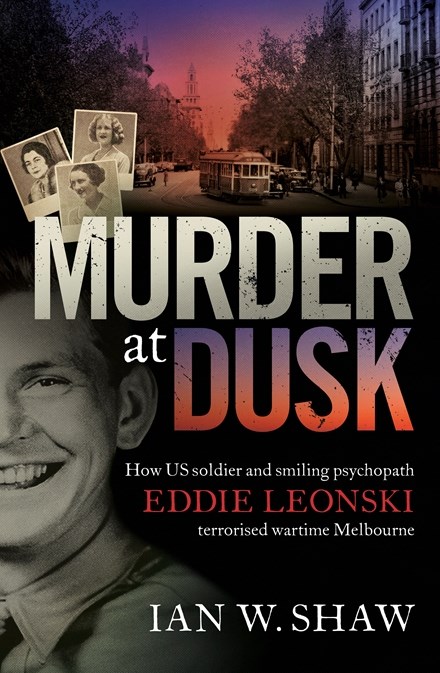

Derek Abbott reviews Murder at Dusk: How US Soldier and Smiling Psychopath Eddie Leonski Terrorised Wartime Melbourne by Ian W. Shaw

Ian Shaw has produced a comprehensive retelling of the real events in Melbourne in May 1942 involving an American soldier, Eddie Leonski, and three women whom he murdered. The story is not unfamiliar; it has been covered at length by other writers and given passing mention in scholarly histories of the home front. Leonski, the product of a family riven by drunkenness, violence and mental illness, has a history of petty criminality and violence that continues after his enlistment in the United States Army.

At Leonski’s trial, three medical specialists will agree that he is sane but has psychopathic tendencies. He is not a mixer and makes few friends in the Army nor does it provide him with a structure that might have channeled his tendencies in less harmful directions. The author describes a man with a simple view of women – either saints (mainly his mother) or sinners (most of the rest). Arriving in Melbourne with the first units of American troops, Leonski has few duties and a great deal of spare time. Discipline in his camp on Melbourne’s Royal Park seems fairly lax, the soldiers are a long way from home but also a long way from the war. Heavy drinking is one way of passing the time, at least for some, including Leonski.

At Leonski’s trial, three medical specialists will agree that he is sane but has psychopathic tendencies. He is not a mixer and makes few friends in the Army nor does it provide him with a structure that might have channeled his tendencies in less harmful directions. The author describes a man with a simple view of women – either saints (mainly his mother) or sinners (most of the rest). Arriving in Melbourne with the first units of American troops, Leonski has few duties and a great deal of spare time. Discipline in his camp on Melbourne’s Royal Park seems fairly lax, the soldiers are a long way from home but also a long way from the war. Heavy drinking is one way of passing the time, at least for some, including Leonski.

Eddie Leonski is an opportunistic killer. His victims are approached in the street or in a bar and, trading on the superficial glamour attaching to US servicemen and the readiness of Australians at that time to be welcoming, he gets close to the women without arousing suspicion. All are strangled and Leonski arranges their bodies to suggest their supposed sexual degradation; killing is not enough, even in death the women must be further humiliated.

The investigation of the murders is carried out by the Victoria Police and, once it is clear that the killer is a US soldier, the US military police. The local police emerge well from Shaw’s telling; they are efficient, try to avoid sensationalism, and, given the publicity that increases with each murder, identify Leonski fairly easily. He had attacked other women who had escaped from him, so there are witnesses and other evidence. Nor did Leonski make any great efforts at concealment.

By agreement between the governments of the USA, the Commonwealth and Victoria regarding offences involving American servicemen, Leonski is subject to American military law, tried by Court Martial and sentenced to death. He is hanged at Pentridge Gaol on 9 November 1942.

In telling this fairly straightforward story, Shaw brings together brief biographies of the main characters, including the Victorian policemen and the principal US participants, mentions the naval and military campaigns that dominated the news headlines, and examines the arrangements between the Australian and US governments to manage the US military presence. Thus the book provides a series of snapshots of the impact of the war on Australia and of the arrival of the American troops on that rapidly changing society.

The author catches the mood of Australia in the early months of 1942 with the rapid Japanese expansion across South-East Asia and the western Pacific, the near panic following the fall of Singapore and the bombing of Darwin in February, and the welcome given to the Americans who started arriving in the same month. The US troops were widely seen as saviours who would rescue Australia from the Japanese menace.

As Michael McKernan has pointed out in All In! Fighting the War at Home, most Australians’ knowledge of America was derived from Hollywood movies and, at first, the troops seemed to confirm that glamorous image, better dressed, with plenty of disposable cash and more social sophistication than their Australian counterparts. The warmth of the welcome grated on some but the resentments that emerged on both sides and the ‘Battle of Brisbane’ and other violent incidents were still in the future.

The area, Gatehouse Street, Parkville, where Leonski murdered his third victim, Gladys Hosking (Pinterest)

The area, Gatehouse Street, Parkville, where Leonski murdered his third victim, Gladys Hosking (Pinterest)

The book goes to some lengths to create a sinister atmosphere appropriate to the events it describes, from the title Murder at Dusk (even though none of the murders happened at dusk) to the emphasis on the partial blackout – the ‘brownout’ – imposed on Melbourne in case of air attacks. The author sometimes gives in to the temptation to indulge in the gothic: did Leonski really think to himself after the first murder that ‘if there was greatness within him, it was greatness that came from his ability to recognize the moment of destiny … If he was to kill again, and he felt strongly that he should … ‘

Yet the image of a dark and threatening city is at odds with the apparent confidence of all the victims. None was very young and only the second conformed to any degree to the image of someone out for a good time. The first victim declined an offer from a male friend to accompany her as she went to catch a tram at one in the morning, the second spent the evening drinking with Leonski and allowed him to walk her to her front door, where he killed her, and the third, having almost literally bumped into him in the street, was walking with him back to his camp as he claimed to be lost. While real apprehension about the safety of women out alone did emerge as the crimes continued, this seems to have been against an existing sense that Melbourne was quite a safe city for unaccompanied women.

The Australian and US authorities cooperated well throughout. All sides were clearly sensitive to their own reputations and had an interest in the matter proceeding to a conclusion without controversy; the Australians to demonstrate both their appreciation of the US presence and their own professionalism, the Americans to ensure that their own citizens were treated fairly but also to reassure Australians that they could rely on the US to punish their own where necessary. Once suspicion fell on a US serviceman the Victorian police got full cooperation from the American military and once Leonski was arrested and responsibility for his detention and trial by court martial passed to the American authorities, the Victorian and Commonwealth governments were equally cooperative.

The negotiations between the various governments and General Douglas McArthur’s staff, the legal basis for the court martial and its conduct, all of which are covered in some detail, comprise the least familiar and thus most interesting part of the book. As described, the proceedings seem to have been scrupulously fair. The court martial consisted of 11 officers and a death sentence required unanimity. Both prosecution and defence counsels had legal backgrounds and experience in civilian life and an appropriately qualified three-person medical panel was brought together to assess Leonski’s mental fitness.

Once Leonski’s fitness was determined his conviction was certain. However, even after conviction the decision of the court had to be confirmed all the way up the chain of command to McArthur’s headquarters, to Washington and to the President.

The book finishes on an appropriately chilling note given the nature of the events it describes. Leonski is taken from the City Watch House by US military police in the early hours of the morning of 9 November, driven to Pentridge and hanged by an anonymous hangman.

This is an interesting and informative book: part who-done-it and part vignette illustrating the social and political history of Australia in World War II, though sometimes the author’s speculations on Leonski’s interior life detract from his otherwise measured tone.

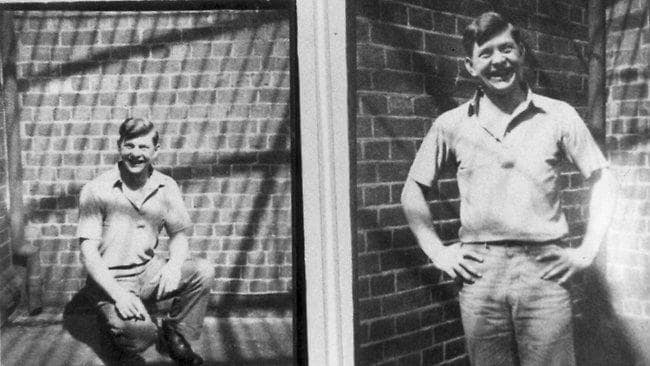

Leonski in the City Watch House a few days before he was hanged (Herald-Sun)

Leonski in the City Watch House a few days before he was hanged (Herald-Sun)

* Derek Abbott is a retired Senate officer. He has done reviews for Honest History on What-ifs in history, the Commonwealth today, Monash and Chauvel, Australian home defence in World War II, The Silk Roads, Victor Trumper, sport, Australian foreign policy, World War I at home, Duchene/Hargraves and the discovery of gold, Charles Todd of the Overland Telegraph, and other subjects.

Film of Melbourne in 1940 and 1942.

Herald-Sun article from 2012 on the Leonski murders.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.