‘Federated Australia’s first champion’ (review of Haigh on Trumper), Honest History, 25 September 2016

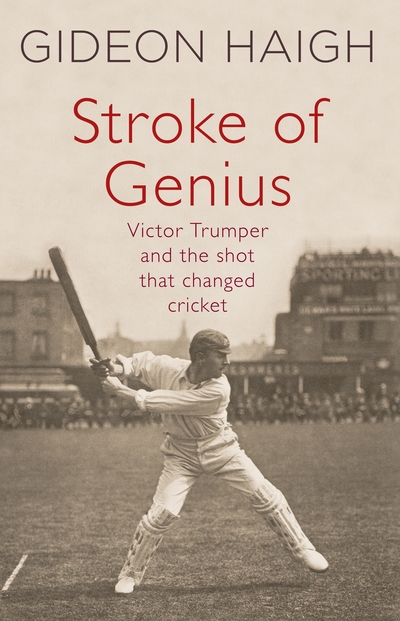

Derek Abbott* reviews Gideon Haigh’s book, Stroke of Genius: Victor Trumper and the Shot that Changed Cricket (2016)

Muhammad Ali, young, brash and confident, mouth agape (‘Get up and fight, you sucker’) looms over the prone Sonny Liston, old, slow and beaten. It is one of the great sporting photographs and, as Gideon Haigh writes in this stimulating and rewarding book, like all powerful images it floats free of its immediate subject and ‘conjures an era, an attitude’. Liston was heavy on his feet, no stylist, a puncher. He trailed an odour of crime and corruption, he was an associate of gamblers and gangsters, but at the same time representative of generations of black Americans exploited for profit by their white managers and promoters.

Ali was the antithesis of Liston, ‘pretty’, stylish, all fast hands and constant movement in the ring, taking no shit from anybody. The image came to embody the 1960s, the civil rights movement and the profound changes taking place in American society, particularly with the accretions of Ali’s later life – opposition to the Vietnam War, the Black Muslims and finally something close to national hero.

Ali was the antithesis of Liston, ‘pretty’, stylish, all fast hands and constant movement in the ring, taking no shit from anybody. The image came to embody the 1960s, the civil rights movement and the profound changes taking place in American society, particularly with the accretions of Ali’s later life – opposition to the Vietnam War, the Black Muslims and finally something close to national hero.

Haigh comments that this photograph illustrates the power of the image because, far from illustrating a titanic moment, it comes at the end of a ‘seven round squib’ and Liston is widely believed to have taken a dive. But, ‘None of this mattered. “This photograph became the way people wanted to see Ali …”.’ There is an irony then, in that Haigh has conflated two fights: the seven round title fight in Miami Beach in February 1964, with the then Cassius Clay as challenger, and a rematch in Lewiston, Maine, in May 1965.

The first fight was hardly a squib, though its ending was an anti-climax; Ali evaded Liston’s assault in the early rounds, increasingly asserted his authority and in the sixth hit Liston almost at will. Ali won the world title when Liston declined to answer the bell for the seventh. The second fight, at which the famous photograph was taken, lasted barely two minutes. Ali was the defending champion and Liston went down in the first round to a glancing blow that didn’t seem to have much power. That, Liston’s reputation, and a confused count, led to accusations of a fix.

Fortunately, since I don’t want to feel like a young Arthur Mailey taking Trumper’s wicket – Mailey said he ‘felt like a boy who had killed a dove’ – Haigh’s error, if anything, strengthens the point he is making: reality adapts to the image. Ali winning the title should have been a climactic moment with the old, corrupt champion flat on the canvas, the dawning of a new era. So that is what the photograph shows – ‘believing is seeing’.

And so to Victor Trumper. In Stroke of Genius Gideon Haigh brings together the early history of Australian cricket, of photography, and Trumper’s life, to create the history of an image. Haigh reminds us that we have lost the sense of how difficult it once was to capture action in sport. Early representations of cricket tended to show ‘landscapes’, in which the action was distant and static with the crowd occupying the foreground. Individual players and their strokes were illustrated in caricatures. Early photography observed these conventions; equipment could not catch action or provide close-ups. Trumper’s contemporaries often found words inadequate to describe his qualities and pleaded that ‘you had to have seen him; then you would understand’.

George Beldam was a good English county batsman and enthusiastic amateur photographer. Having found sportsmen’s explanations of their art to be inadequate, he wanted to use photography to break down their actions so that their technique could be properly described. By the early years of the 20th century he had equipment that could ‘stop’ movement and enable him to achieve his objective. Trumper’s photograph was one of a series included in a book Beldam published (with commentaries by the England cricketer, CB Fry) in 1905, Great Batsmen: Their Methods at a Glance. The photograph was completely contrived. It did not purport to be of an actual match; we cannot be confident whether Trumper was facing a bowler or simply demonstrating the stroke. Yet the image came to epitomise an approach to the game that appeared gracious and carefree and would be invoked by later generations as a rebuke to ruthless run accumulators, safety-first tactics and unsporting sledgers.

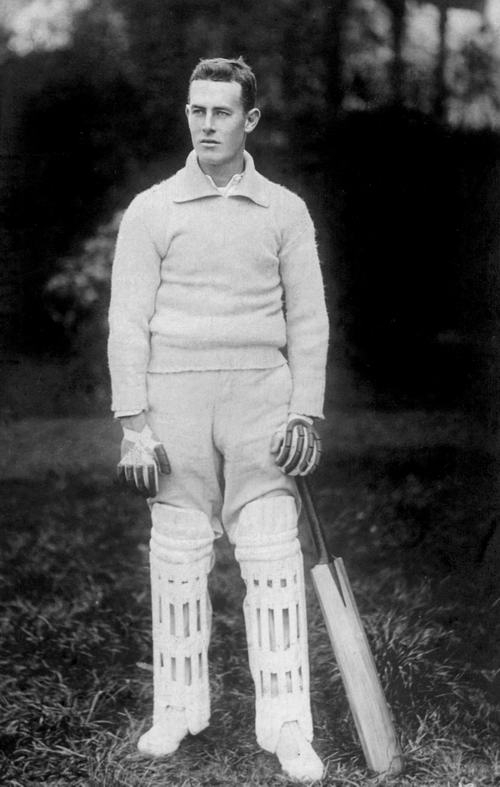

Victor Trumper (downatthirdman)

Victor Trumper (downatthirdman)

‘Jumping out for a straight drive’ may well be the most evocative picture in cricket. The batsman is a yard out of his ground, and front foot in mid-air, bat at the top of its backswing and the tension in his limbs all indicate forward movement. The mind’s eye can easily create the frames that come before and after.

The quality of the picture can be appreciated by comparing it with the photograph of modern batsman Dean Jones replicating the stroke in 1990. Jones, one of the most dashing batsmen of his generation, is made to look static, weight on his back leg and body too straight. Trumper’s stroke is at once bold and graceful; its image became freighted with meanings after Trumper’s early death from illness in 1915 and that of so many of his contemporaries in the Great War. (A video clip of Trumper’s funeral.) Peter Stanley, in his contribution to The War at Home wrote that ‘The impact of the Great War on Australia … arguably ended the optimistic, unified, progressive Australia that the world so admired before it, when, as Henry Lawson wrote in 1913, “hopes ran high … we thought that we would never die”’. Trumper’s memory and his image became bound up with that sense of loss.

English cricket writer Neville Cardus coined the phrase ‘a golden age’ to describe Edwardian cricket; he ‘longed for a better time, a pristine bygone age’, an age epitomised in his mind by Trumper. Yet Cardus’s Trumper was already in the 1920s becoming a mythologised figure. He survived in the recollections of aging contemporaries and, as the memories faded, in the remarkable photographs taken in 1905 by George Beldam. Trumper’s name became a measure of greatness. Rising batsmen were hailed as ‘the new Trumper’. The quality of tennis and football players, golfers, jockeys and – only in Australia – a blue kelpie from Cootamundra was established by reference to Trumper. The real Trumper, a more complex figure, disappeared from view.

The reality was far from the image. The early Australian cricket sides that toured to England were in effect joint stock companies in which the players were shareholders, selectors and managers. Funded with advances, they depended on gate takings both to repay their debts and to provide an income for the players, who would be away from Australia for five or six months. English cricket was divided between Gentlemen and Players, amateurs and professionals; the former captained sides and ran the game. Professionals did what they were told, entered grounds by a separate gate and were identified by surname alone.

In this milieu the Australians’ status was uncertain: they were determined to be accepted as equals by the leaders of the game but they were aware of the need to earn money; there was fertile ground for hypocrisy and condescension. A contemporary English observer noted in 1901 that ‘[t]he Australians have reduced to a fine art the practice of making the English three-day match last its full three days, and in doing so they have dealt a blow to the best interests of English cricket’.

Australian cricket was characterised by ‘patience and stamina’ that Haigh summarises as rooted in ‘gate-money mindedness’. It was in this context that Trumper’s dash and quick scoring – ‘He has no style, yet he is all style’ – in the summer of 1902 not only delighted observers but helped to invent modern Australian cricket’s reputation as ‘innately aggressive’. Trumper was recognised as the heir to WG Grace as cricket’s premier batsman and, in the year after the creation of the Commonwealth of Australia, he became the first champion of the new nation.

While Trumper was a remarkable batsman and, by most contemporary accounts, a thoroughly decent, generous and modest man, he was no ‘pedigreed amateur’, in Neville Cardus’ phrase. Learning his cricket in the cobbled lanes of working class Surry Hills in Sydney, Trumper struggled to make ends meet financially throughout his life and his career was not without controversy.

At various times Trumper attracted criticism for considering offers to play county cricket as a ‘shamateur’, provided with an undemanding job on the side (like a number of English ‘Gentleman’ players) and to write a newspaper column on tour, in breach of the players’ touring conditions. He was deeply involved in the formation of the New South Wales Rugby League and opposed both the NSW Cricket Association and the Board of Control as they sought to take the management of the game out of the hands of the players. Trumper was one of the six leading players who withdrew from the 1912 tour of England in protest against the Board’s control of the tour. Even his batting was regarded in some quarters as too daring. In 1905 The Field grumbled ‘[i]t may be doubted whether the plan of making a tour de force of every stroke and trusting almost entirely to the “eye”, of which Trumper is so brilliant an exponent, can be recommended for long wear’.

All of this was to fade, leaving only the image. Gideon Haigh, surely our best writer on sport and history, is to be thanked for bringing it back to life.

Trumper’s grave, Waverley Cemetery, Sydney (espncricinfo)

Trumper’s grave, Waverley Cemetery, Sydney (espncricinfo)

* Derek Abbott is a retired Senate officer with a history degree from Aberdeen University. He has reviewed a number of books for Honest History.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.