Derek Abbott*

‘If only we had more what-ifs: a book of counterfactuals’, Honest History, 16 April 2018

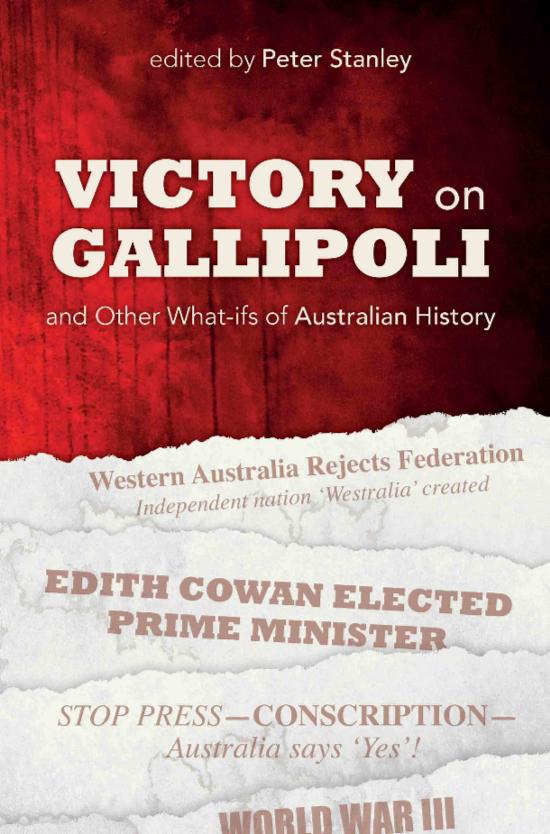

Derek Abbott reviews Victory on Gallipoli and Other What-ifs of Australian History, edited by Peter Stanley

Jack Lang prepares to cut the ribbon and open Sydney Harbour Bridge. In the background, two men, mounted and in uniform, one of them perhaps the worse for drink, engage in an unseemly brawl as each tries to pre-empt Lang. They are taken away by the police and Lang proceeds unmolested to complete his task. One of the men is Francis de Groot and the other is Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant.

It didn’t happen that way, of course: de Groot did cut the ribbon and Morant was long dead. But Craig Wilcox speculates that such an act would have been entirely in character for Morant – had his sentence been commuted. By giving Morant an afterlife as a disgruntled contrarian ‘with a fondness for the bottle’, Wilcox is able to illuminate his subject’s character and provide an alternative and perhaps more real view of the man than the mythologised Breaker of Bruce Beresford’s 1980 film.

It didn’t happen that way, of course: de Groot did cut the ribbon and Morant was long dead. But Craig Wilcox speculates that such an act would have been entirely in character for Morant – had his sentence been commuted. By giving Morant an afterlife as a disgruntled contrarian ‘with a fondness for the bottle’, Wilcox is able to illuminate his subject’s character and provide an alternative and perhaps more real view of the man than the mythologised Breaker of Bruce Beresford’s 1980 film.

As Peter Stanley notes in his introduction to this collection of ‘What-ifs’, speculating on what might have been, had one event turned out differently, can be both entertaining and enlightening. Had the Gallipoli campaign been successful, had France colonised Western Australia, had Batman’s treaty with the Port Philip people been recognised in law or, indeed, had somebody in the Australian dressing room in Cape Town at lunch on Day 3 said, ‘Don’t be bloody stupid’, then the future in each case might have been quite different. The extent and nature of those differences fuels enthusiastic debate in pubs and common rooms and at high tables.

Stanley reminds us that counterfactuals can also serve as useful correctives to an approach to the study of history that sees ‘the past as somehow immutable … that has led inevitably to the present’. Whether it be the Whig interpretation of the inevitable triumph of liberal democracy, the mechanistic grindings of the dialectic leading inexorably to a Marxian utopia, or God’s vast eternal plan, such determinism is to be avoided. Yet, to suggest that the past is no more than a random assemblage of individuals and contingencies is equally misleading: there are underlying factors – geography, demographics, culture, economics – that do shape the response of individuals and societies to particular events.

If counterfactuals are to serve a valid scholarly purpose they have to be tightly disciplined. By illuminating the range of possible outcomes in any given situation counterfactuals may deepen our understanding of how and why a decision was made or a particular outcome occurred. The further counterfactuals diverge from established facts, the more additional assumptions are made as to what would flow from the initial changed event, the more the counterfactual becomes pure fiction and the less it illuminates real events. ‘What-ifs’ all too easily become, in the words of historian Sir Richard Evans, ‘If-onlys’, reflective of the author’s desires or biases.

This collection has many examples of both approaches. In the essay that gives this volume its title, Peter Stanley avoids the pitfalls. Victory on Gallipoli, the product of a more realistic plan and better execution, does not result in a triumphant ANZAC march on Istanbul or glorious victories in the Balkans against Austria-Hungary which dramatically shorten the war and confer renown on the young nation. Instead, a hard fought victory on the peninsula enables the Royal Navy to pass through the Dardanelles and compel the surrender of Istanbul. The Australians – ‘Bored, sick, poorly supplied [and] neglected’ – are distributed across eastern Thrace as an occupying force, engaged in an increasingly ‘dirty war’ which becomes very unpopular back home. Stanley avoids heroic speculations: Russia is not saved from revolution, the bloodbath on the Western Front is not avoided – though he does allow Mustafa Kemal to rally nationalist opposition in Anatolia.

In other essays, Stanley speculates on the impact on Australia, and particularly on the Anzac legend, had HMAS Australia rather than its sister ship HMS Indefatigable been sunk with catastrophic loss of life at the Battle of Jutland in May 1916, or had Australian troops been diverted to India to replace British regulars on garrison duty. This move was considered in some quarters and British troopships carrying Territorials (reservists) to India did pass ANZAC troopships in the Suez Canal.

In this Stanley counterfactual, the Anzac legend becomes less ‘khaki’, with the RAN’s role in the war given greater prominence while the role of an army of occupation is not the foundation for a heroic myth. The post-war returned services movement is less powerful, being deeply divided between those who saw combat and those who did garrison duty – with the result that returned servicemen in Australia do much worse than in other allied nations.

Edith Cowan (Wikipedia)

Edith Cowan (Wikipedia)

Hamish Maxwell-Stuart imagines an alternative history of Tasmania in which the (real) bushranger Michael Howe, in cooperation with the Big River People creates a formidable force that the British authorities ultimately have to recognise and draw into the structure of British rule, using them as a frontier force in the Black War. Maxwell-Stuart draws on examples from the colonial history of the West Indies and South Africa, where such compromises were made. He, like Stanley, avoids an ‘if-only’ outcome. Race relations in Tasmania remain tortured, indigenous people remain marginalised and deep divisions persist between the descendants of the various groups.

Had women entered Federal Parliament a generation earlier than they in fact did – say, Vida Goldstein in 1914 and Edith Cowan in 1918 – then the place of women in Australian public life and in society generally might well have been very different. These two essays, by Janette Bomford and Clare Wright respectively, demonstrate the possibilities of the genre. Wright puts Cowan into Federal Parliament in 1918 (instead of the Western Australian state parliament in 1921) and, with a couple of imaginative leaps, has her serving as prime minister in the early 1920s, introducing progressive legislation on the status and rights of women and children. However, facing electoral disaster, she gives way to SM Bruce in 1925 and retires from public life. Her legacy is to have prepared the way for other women, starting with Enid Lyons as Australia’s second female prime minister in the 1930s.

In contrast, Bomford makes Vida Goldstein’s election the starting point of a total recasting of Australian history that involves a number of heroic assumptions. Having quite reasonably speculated that Goldstein would have been an even more effective campaigner against conscription and militarism generally as a member of parliament, Bomford has her included in the Australian delegation to Versailles, where she convinces Lloyd George of the wisdom of a moderate peace based on Wilson’s Fourteen Points. Germany, now a constitutional monarchy, is welcomed back into the international community and an obscure Austrian infantryman emigrates to Brazil. Australia becomes a pacifist nation, distancing itself from Britain, thus avoiding future military entanglements, and becomes an ally of similar peace-loving social democracies and a leader in its region. If only.

Two other political ‘might have beens’ have Gough Whitlam and Paul Keating narrowly avoiding defeat in 1975 and 1996 respectively. Both men are suitably chastened and preside over governments that combine progressive policies, competent management and properly managed transitions of leadership, leading to extended periods of sound centre-left government with frustrated opposition parties rendered increasingly ineffectual. The Liberals even turn, in desperation, to Bronwyn Bishop! In contrast, in a reimagined On the Beach, Australia survives nuclear war in the northern hemisphere isolated and embattled, but the times suit John Howard.

Sport, like war, lends itself to what-ifs: a close result can, plausibly, be reversed. Indeed, it is the what-ifs that keep the supporters coming back season after season. Michael McKernan has South Melbourne’s star player, Bob Pratt, avoid injury prior to the 1935 Victorian Football League Grand Final and kick his side to victory over Collingwood, sparking a run of premierships for South. I had expected this to lead to a dominant and financially viable South Melbourne remaining a power in the VFL while Sydney was represented in the newly created AFL by a team playing in black and white. McKernan avoids the temptation.

Walter Kudrycz takes on the much more demanding task of imagining a glorious future for Australian soccer. His starting point has Australia beating (eventual world champions) West Germany in a group game at the 1974 World Cup. The enthusiasm this generates allows Frank Lowy to establish a successful national league 30 years earlier than actually was the case. Building on this successful domestic competition Australia, the host nation, beats Italy to win the 1994 World Cup. Tell him he’s dreaming.

Charles Kingsford Smith depicted in 1935, not long before his presumed death (Acepilots/Hall of Fame of the Air)

Charles Kingsford Smith depicted in 1935, not long before his presumed death (Acepilots/Hall of Fame of the Air)

There are a number of other contributions that will challenge and entertain the reader: Western Australia either becomes a French colony in the 1820s or remains independent; Batman’s treaty with the Aborigines is recognised in the 1930s as having legal force and provides the basis for a politically powerful indigenous movement; Paul McCartney and his family emigrate to Australia in 1957; like Breaker Morant, Charles Kingsford Smith is given an afterlife.

Sir Richard Evans, reviewing historical counterfactuals some years ago, noted that the genre in Britain tended to be ‘more or less a monopoly of the Right’,[1] with Britain avoiding European entanglements either military or bureaucratic, retaining its Empire and preserving its national vigour by rejecting the morally debilitating welfare state. These counterfactuals are essentially backward looking, trying to project a glorious past onto a humdrum present.

In contrast the ‘if-onlys’ in this collection tend to be of the left, implicitly expressing the view that at various stages Australia has failed to realise its potential and reminding us that we could have done better. In reading them, I was reminded of Peter Stanley’s conclusion to his contribution to The Centenary History of Australia and the Great War:

The impact of the Great War on Australia, Judith Smart and Tony Wood judged, was “essentially negative, reactionary and destructive of tolerance”. It arguably ended the optimistic, unified, progressive Australia that the world had so admired …[2]

These ‘if-onlys’ clearly invite us to rediscover that ‘optimistic, unified, progressive Australia’.

* Derek Abbott is a retired Senate officer. He has done reviews for Honest History on the Commonwealth today, Monash and Chauvel, Australian home defence in World War II, The Silk Roads, Victor Trumper, sport, Australian foreign policy, World War I at home, Duchene/Hargraves and the discovery of gold, Charles Todd of the Overland Telegraph, and other subjects.

[1] Richard J Evans, Altered Pasts: Counterfactuals in History, Brandeis University Press, Lebanon NH, 2014, p.51.

[2] John Connor, Peter Stanley, Peter Yule, The War at Home: The Centenary History of the Great War, vol 4, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2015, p. 230.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.