Derek Abbott*

‘Griffith Review 59: a timely survey of “Commonwealth Now”’, Honest History, 28 February 2018

Derek Abbott reviews Griffith Review 59: Commonwealth Now, edited by Julianne Schultz and Jane Camens

Given the current and continuing debates in this country over ‘changing the date’ and the history wars, one might assume that Griffith Review was joining the discussion of the state of the Australian Commonwealth. But, no, No. 59 is looking at that other Commonwealth, the ‘British’ one, the one that intrudes on our sporting consciousness every four years and almost not at all otherwise.

Michael Wesley’s essay in this collection acknowledges that the Commonwealth made a useful contribution to the ‘demise of white rule in southern Africa’, but since then, ‘[w]hen this coalition of whimsy meets a hard policy issue, its solidarity falls victim to its diversity, while its breadth of membership can’t deliver real weight and gravitas …’

Michael Wesley’s essay in this collection acknowledges that the Commonwealth made a useful contribution to the ‘demise of white rule in southern Africa’, but since then, ‘[w]hen this coalition of whimsy meets a hard policy issue, its solidarity falls victim to its diversity, while its breadth of membership can’t deliver real weight and gravitas …’

To Wesley, the Commonwealth exists in the soft afterglow of the never-setting sun, sustained by sentimentality and ‘an act of forgetting what constructed it in the first place’.

The act of forgetting may be necessary to the functioning of the Commonwealth but – as is clear from this collection of essays, memoirs and short fiction – for many of the citizens of the former Empire, forgetting is not an option as they confront the legacies of colonialism. As one contributor comments, ‘We are meant to be compliant and complicit in the whitewash of our history, in the convenience of colonial amnesia and its glaring omissions’.

Julianne Schultz notes in her introduction that the New Commonwealth, formed as the newly independent former colonies joined the established Dominions, represented ‘an ingenious way [for Britain] to hold on to influence’. Britain’s membership of the European Union undermined that project and pushed aside any serious effort to come to terms with its Imperial legacy.

Brexit has, however, given a boost to the idea of ‘Empire 2.0’, with trade with the Commonwealth somehow replacing the EU. Schultz reminds the reader of the wonderful pre-emptive strike against such an idea from the Economist in 2011: ‘Talk of the Commonwealth forming the dynamic, like-minded, free-trading core of a new British global network for prosperity is, to use the technical term, cobblers’.

Cobblers it may be, but opinion polling in Britain suggests that belief that the Empire was a ‘good thing’ remains strong in that country; the idea of ‘Empire 2.0’ is attractive to a significant minority. Stuart Ward sees such thinking as but the latest instalment of Britain’s search for a post-Imperial role.

Considerable effort has gone into projecting an image of the British Empire as essentially benign: gained in a fit of absence of mind, selflessly bestowing the benefits of the rule of law, education, modern science, and the rest on an often ungrateful populace. Australia is not lacking in proponents of that view; there come to mind from 2008 Brendan Nelson’s ‘involuntary sacrifice’ of Aboriginal Australians ‘to make possible the economic and social development of our modern Australia’, or Tony Abbott’s recent assertion that ‘on balance’ British settlement was good for Aboriginal people ‘because it brought Western civilisation to this country’.

For a number of contributors the Commonwealth should try harder to give substance to its ideals, for example, the oft-cited rule of law. As Salil Tripathi, an Indian writer living in England, notes, repressive colonial-era laws underpin the abuse of human rights in many Commonwealth countries. Godfrey Smith comments, with admirable understatement, ‘the rule of law as a force for good has not been uniformly felt …’ Smith attributes this, in part, to the persistence of antediluvian traditions emphasising the pomp and circumstance of the law rather than its principles: ‘abolition [of those traditions] would provoke rebellion by bar associations across the Commonwealth’.

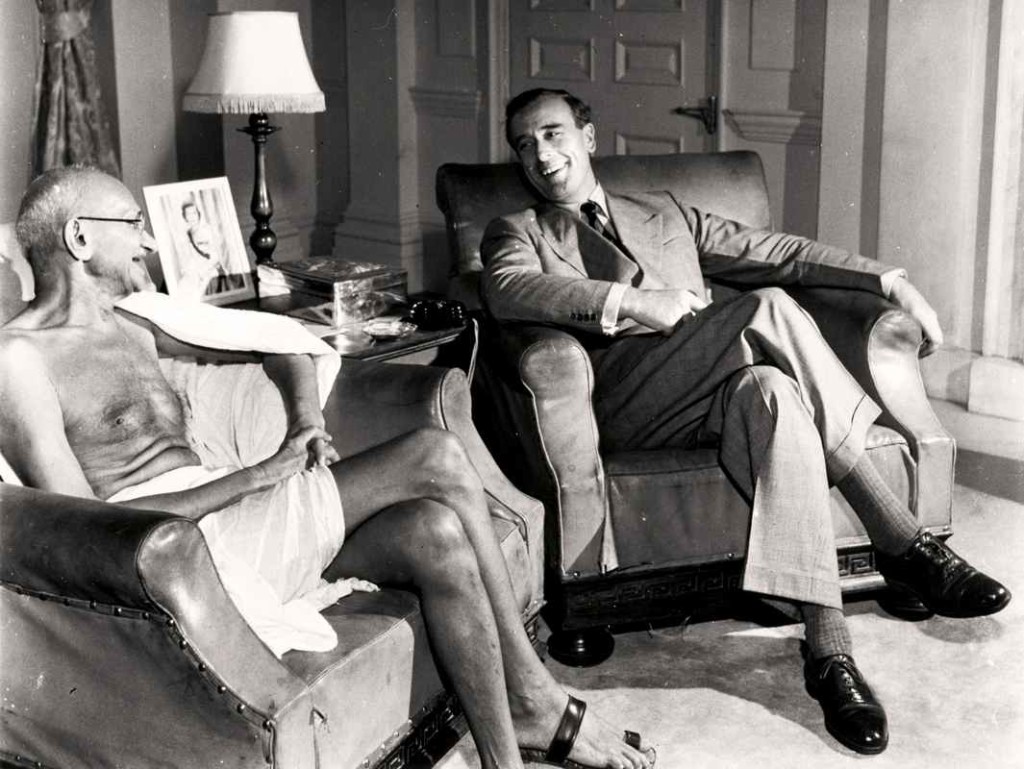

Lord Mountbatten, last Viceroy of India, and Gandhi, c. 1947 (historydiscussion/donnamoderna.com)

Lord Mountbatten, last Viceroy of India, and Gandhi, c. 1947 (historydiscussion/donnamoderna.com)

Tripathi comments on the insularity and inadequacy of the history taught in British schools and the popularity of films such as The Viceroy’s House – described as a ‘servile pantomime’ by a Pakistani critic – Dunkirk and Churchill, films that paint largely positive views of Britain and its leaders. As the author notes, the compassionate Churchill of the eponymous film, worrying about casualties on D-Day, was very selective in bestowing that compassion; it did not extend to the people of Bengal. This narrative has no room for what was more typical – the wholesale destruction and remaking of economies, environments and cultures to benefit the colonisers.

The legacies of Empire range from the structural to the deeply personal. In ‘Imperial amnesia’, Shashi Tharoor notes that the arbitrary drawing of international boundaries, the forcing together of ‘disparate peoples’ into ‘colonially created states’ and the distorted physical and social infrastructures created to benefit colonial powers continue to drive inter- and intra-state conflicts.

Urvashi Butalia describes the efforts of women’s groups to create cross-border networks in South Asia, in large part to try to overcome the divisions that flowed from decolonisation. Bernice Chauly, in describing a massacre of Chinese workers by a platoon of the Scots Guards during the Malayan Emergency, notes the legacy of divide and rule, ‘the policy [the British] knew best’, in creating Malay nationalism. A number of the essays comment either directly or implicitly on the divisions created by the arbitrary shipping of peoples around the Empire to provide cheap or at least quiescent labour, with the result that, from the Pacific to Malaysia to the West Indies, introduced minorities struggle to assert equal rights.

Diana McCaulay, the descendent of Portugese plantation owners and black slaves, is Chief Executive of the Jamaican Environment Trust. Her memoir, ‘A pale white sky’, brings together the personal and the structural. As an environmentalist, she is profoundly aware of the damage wrought by the hubris of the colonisers. The Jamaican landscape is dominated and shaped by introduced species of plants and animals, the land itself worked by the descendants of slaves brought in to replace the original inhabitants.

McCaulay describes herself as ‘more of the coloniser than of the enslaved’ and encapsulates the dilemma of the settler: ‘I was not of Jamaica because I was not of the people … But I knew I was of the land.’ The Commonwealth, and indeed humanity in general, needs ‘to face the truth about our inheritances … to own our complicities’.

The Bangladeshi poet Kaiser Haq describes his upbringing in a loyal pro-British family, where his father saw independence as an opportunity for the ‘Brown Sahibs to come into their own’, retaining all the hierarchies of Empire. He was educated in – and continues to write in – English. Though Haq considers himself ‘something of a pariah’ in a country where language is deeply bound with national identity, he is not alienated from his native culture, considering himself ‘post-colonial’ and ‘post-Commonwealth’ in a world that ‘is becoming increasingly transnational’.

It is reported that the Commonwealth Secretariat and the Palace are wrestling with the question of who will succeed Her Majesty as Head of the Commonwealth. Apparently Charles III cannot take it for granted that he will get the job. Would the Commonwealth’s diminishing band of supporters retain their enthusiasm if invitations to Commonwealth Day at Westminster Abbey (brilliantly described by Selina Tusitala Marsh) and Royal garden parties were replaced by celebrations in some remote and sweaty outpost – Canberra perhaps? It would be an appropriate irony if, having survived many disagreements and conflicts over important issues, the loss of the royal connection finally consigned the Commonwealth to history.

The Prince of Wales (loopvanuatu). HRH will open the Commonwealth Games in Queensland. He will also visit Vanuatu.

The Prince of Wales (loopvanuatu). HRH will open the Commonwealth Games in Queensland. He will also visit Vanuatu.

Griffith Review, as always, has provided readers with a diverse and stimulating collection of writers and views on the Commonwealth. In contrast to the ‘act of forgetting’ on which the Commonwealth depends, the unifying theme of this collection is the importance of honest remembering of the reality of Empire and its legacies. To most of the contributors, the Commonwealth itself seems to be of little significance. Perhaps it is time that we were all post-Commonwealth.

* Derek Abbott is a retired Senate officer. He has reviewed books for Honest History on Monash and Chauvel, Australian home defence in World War II, The Silk Roads, Victor Trumper, sport, Australian foreign policy, World War I at home, Duchene/Hargraves and the discovery of gold, Charles Todd of the Overland Telegraph, and other subjects.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.