Rationale

Critiquing the Anzac-centred received view of Australian history necessarily involves forensic examination of the work of our premier commemorative institution, the Australian War Memorial. The Memorial – rather surprisingly, in view of its interest in warlike matters – has not been willing to contest or debate with critics like Honest History. This is disappointing; perhaps a change will come eventually. Other religious and cultural institutions have eventually been prepared to argue for and defend their case in the marketplace of ideas.

If the day for that debate comes, this article will be useful as a collection of links to relevant items on the Honest History website. Most have been researched and written by David Stephens, secretary of the Honest History coalition and editor of its website, though some have been ‘workshopped’ with other people.

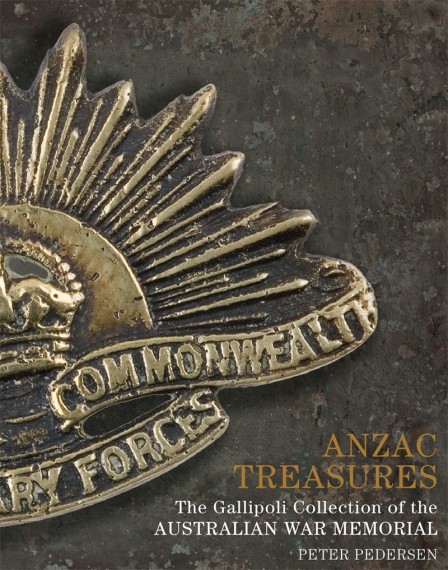

Anzac Treasures

Anzac Treasures: The Gallipoli Collection of the Australian War Memorial was a beautifully produced, big door-stopper of a book, brought out for the Anzac centenary. Our review of the book said it included some nice writing by Peter Pedersen and pictures of every imaginable (and some unimaginable) war relic but that, leaving aside its production values, it could have been published 50 years ago.

Anzac Treasures: The Gallipoli Collection of the Australian War Memorial was a beautifully produced, big door-stopper of a book, brought out for the Anzac centenary. Our review of the book said it included some nice writing by Peter Pedersen and pictures of every imaginable (and some unimaginable) war relic but that, leaving aside its production values, it could have been published 50 years ago.

We commented on the sanitised view of war that Anzac Treasures presented, as did Alan Stephens in a review about that time of the Memorial’s Afghanistan exhibition, which we cross-referenced. Anzac Treasures, our review concluded, ‘attests above all to the stoicism of ordinary men in impossible circumstances. There is, however, much more that can and should be said about Gallipoli and about war than is said in this book.’

World War I galleries

We did two reviews of the Memorial’s expensively refurbished World War I galleries, here and here. We also cross-referenced Christina Spittel’s critical review in reCollections. We found the rework of the galleries offered less than was promised about what Australia was like before and after the war and, in other respects, was essentially a higher-tech version of what had been in the Memorial for nearly 75 years. So we got an interactive map of Gallipoli, as well as the trusty dioramas, and we got more buttons to press. Some of the presentation aspects, such as lighting and captioning, however, were not up to the standard of the National Library’s smaller Keepsakes show.

We found there was more in the galleries about the Turks than there was before and there was still unquestioning acceptance of the provenance of the alleged Ataturk words (‘Those heroes that shed their blood …’) despite recent scholarship, much of it recorded on the Honest History website. But the ‘new’ galleries show even more clearly that the Memorial is not good on context, the home front and unpleasantness (unless it can be swamped by sentiment). ‘The Memorial is partial, not only because it tells just part of the story, but also because it soft-peddles the ugly bits of what is left, sepia-toning the blood-red and putrid. It takes one side, when it should show all sides.’

Alternative Guide

On Anzac Day 2016 Honest History posted its Alternative Guide to the Australian War Memorial. Intended for secondary students, their teachers and the general public, the Guide walks visitors through the Memorial, asking questions about the Memorial’s emphases and silences. By the end of October 2016, the Guide had been downloaded almost 1700 times. We hope to do a new edition early in 2017. We sent copies of the Guide to each member of the War Memorial Council and offered to give the Council a presentation on the Guide but the offer was declined.

Art collection

Soldier, Russell Drysdale, 1942 (AWM ART92623)

Soldier, Russell Drysdale, 1942 (AWM ART92623)

We included the Memorial’s Reality in Flames exhibition in a piece about three art exhibitions in Canberra. It was a show about the art of World War II and it was a refreshing – if that is the right word, given the subject matter – change from the World War I galleries upstairs.

Reality in flames [our review said] is well organised under headings which show the range of its coverage: the aesthetics of battle; men and women in war; a spirited time; new experiences, exotic and alien; exodus, imprisonment and death; building another world … Reality in flames is a credit to the Memorial’s art team who put it together and to the Memorial’s management who blessed the exhibition.

Unfortunately, on the day we went this exhibition was virtually bereft of spectators.

Children

We have been particularly interested in how the Memorial interacts with children. We have referred often to the remarks of blogger James Rose about how the Memorial ‘imprints’ a sanitised view on young people. We reviewed, in parallel, a War Memorial-Department of Veterans’ Affairs publication, Audacity, and Deeds that Won the Empire, a patriotic pot-boiler from a century ago. The two books had many things in common:

Both Deeds and Audacity are propaganda. They gild the lily, they suppress evidence, they tell only part of the story in the interest of recruiting children to a patriotic cause. If either book finds its way into the hands of today’s children – and Audacity certainly will – it will need to be treated with great care and countered with plenty of other materials which put a more honest and balanced view of the nature of war. Or binned.

We also wrote about the Memorial’s children’s program. Like the book review, the piece was critical. We offered to come and discuss our views with the Memorial’s staff – for them to show us where we were wrong, if that was what happened – but the offer was not taken up.

Public relations

Communications between the Memorial and Honest History have not improved since we began our work. Some of this is described in the article here. The article takes the story from an initial meeting with the Memorial’s then newish director, the Honourable Dr Brendan Nelson (later AO) – ‘We left the meeting feeling bullied, bloodied but unbowed’ – to later attempts by the Memorial’s Communications and Marketing area to control our contacts with the Memorial. We had some fun with this contretemps. We also said this:

We are not the Memorial’s enemies; we are its constructive critics. Some of us now involved in Honest History spent a good part of two years of our lives from 2011 successfully lobbying against a silly plan by some Canberra citizens to build separate World War I and II memorials which would have rivalled what we saw as the “real” – and valued – Memorial. (For more on this.)

Ancient communications: Australian Army, New Guinea, 1944 (AWM 074799)

Ancient communications: Australian Army, New Guinea, 1944 (AWM 074799)

While the Memorial’s communication flow with constructive critics (like Honest History) tends to be intermittent, its chief communicator these days is Dr Nelson. There is an extensive analysis of his speeches in two parts, here and here. Towards the end of the first article, we compared Dr Nelson’s rhetoric with that of King George V a century ago. (The King told his bereaved subjects that their son, father or brother had ‘Died for Freedom and Honour’.) ‘For righteousness and liberty’, said Dr Nelson in a speech in 2015, ‘2 million Australian men and women serve – and have served this nation over more than a century’. The Honest History comment was as follows: ‘From King George to Dr Nelson, the boilerplate commemoration-speak has hardly altered over a hundred years’.

Who goes there?

Honest History did extensive work also on the ‘visitation’ levels to the Memorial over the last 20 years – work that the Memorial claims it has not done itself. We found that, in real terms, compared with Australia’s population, the number of people walking up the steps and into the Memorial has changed very little over that time: in any one year, about 96 per cent of Australians do not go to the Memorial.

This article also reported some puzzling aspects of how the Memorial reports the numbers of users of its website. We could not decide whether the discrepancies in the figures were due to incompetent measurement or an intention to deceive. We have not yet looked at the 2015-16 figures for real or virtual visitors to the Memorial but intend to do so. The Memorial did not wish to comment on our previous articles.

Update 7 February 2017: Honest History looked at the Memorial’s Annual Report for 2015-16 and did some further analysis. We concluded:

the claim of an increase in real visitors – ‘visitors walking through the front doors’ – is not supportable by the Memorial’s own statistics and suggests at least sloppiness, if not an intention to mislead. Similarly, there is still a degree of carelessness, even obfuscation, in the Memorial’s website statistics. Most organisations will gild the lily in presenting statistics but they will usually be cleverer at it than the Memorial is – and they will avoid clanging cock-ups like using last year’s statistics.

Sarah Brasch wrote a perceptive article on whether the Memorial was ‘our national cathedral‘. She included a reflection on the daily Last Post Ceremony.

One of the children’s wreaths sticks in my mind. The card said, “We thank all the Australian soldiers, past and present, who have made our country what it is today”. How exquisitely, how cleverly the Anzac myth is perpetuated as if the whole of time, all of our history, all of those people, all of their efforts, the whole of 1788-1915 and what went before, did not and had not ever existed – or, if it did, there was nothing significant to remark upon.

Straw in the wind

The Memorial has firmly resisted recognising the Frontier Wars, the conflict between Indigenous Australians and settlers, soldiers and native police. While it does not deny that there was such conflict it would rather it be commemorated somewhere else. Honest History wrote up the Memorial’s use of a John Schumann song which referred to the Frontier Wars. We wondered if it might signify a change of attitude. Since then there has been at the Memorial more recognition of Indigenous warriors but they have been ones in uniform.

Agent Orange

Honest History was happy to host Jacqueline Bird for her long article on the long story of the battle of some Vietnam veterans for a rewriting of the official story of Agent Orange and its effects on Australian soldiers in Vietnam. The article recorded that the recent management of the Memorial made some significant breakthroughs on this matter.

Management and oversight

The general community may well know very little about the people who govern the War Memorial, either in comparison with other countries and the Australian states or in the context of the history of the Memorial. This detailed article tried to redress that balance. It noted that

a detached observer looking at the current [War Memorial] Council membership (or, for that matter, its membership at any time over the last 75 years), without knowing who it belonged to, might take it to be the Board of a Naval, Army and Air Force Club rather than of a national war memorial, albeit a club that was doing its best to be welcoming to female members and the younger generation and to keep up its links with military history buffs, particularly philanthropic ones.

(Picture: The Memorial from Mount Ainslie, c. 1940 (NLA nla.obj-151709191)/RC Strangman)

The article suggested a modest reform proposal

to amend the Australian War Memorial Act to allow for Council vacancies to be filled through public advertisement. Positions in the mass armies, air forces and navies of the past were filled by recruitment drives boosted by patriotic advertising; positions on the body which determines how these men and women are remembered could also be filled by advertising and application.

The Minister might still appoint the Chair of the Council, there might still be some ex officio military positions, but the other positions could be filled by qualified and interested members of the community.

Decades on, too much of the control of our national war memorial has devolved to the senior officer cadre and a supporting cast of the Australian version of “the great and the good”. The people should be allowed to take back this role. The remembrance of war – and, more importantly, the prospect of peace – are too important to be left to those who have made a profession out of military activity or a hobby out of military history.

Pictures

Finally, not specifically referring to any past post but important nevertheless, Honest History should send kudos for the Memorial’s amazing collection of photographs, which we have used many times. We have found the collection remarkably free of the often silly usage restrictions and incomprehensible rules of many cultural institutions and photo aggregation websites. We have often said the Memorial is the best in the world at what it does – telling a partial story of war – and photographs is one thing it does really well. (It is a little surprising, though, that the same photographs turn up again and again in publications by the Memorial and by other authors.)

The Honest History site has many other references to the Memorial. The interested reader can pick them up by using our ‘Search’ function. Our Centenary Watch column is also relevant.

11 November 2016 updated

Mena Camp, Egypt, December 1914, a much-used photo from the collection (AWM C02588)

Mena Camp, Egypt, December 1914, a much-used photo from the collection (AWM C02588)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.