‘Our national cathedral?’ Honest History, 15 March 2015

Sarah Brasch* attends the Last Post ceremony at the Australian War Memorial

Unlike Washington DC, Canberra does not have a National Cathedral. But since 17 April 2013 our capital has had something pretty close to it. I recently attended the Last Post ceremony at the Australian War Memorial. [1] This event, ‘farewelling the day’s visitors’ and held almost every day, is a ceremony of religious intensity in a setting worthy of a sacred site. It has a liturgy all of its own and a distinctly Aussie style.

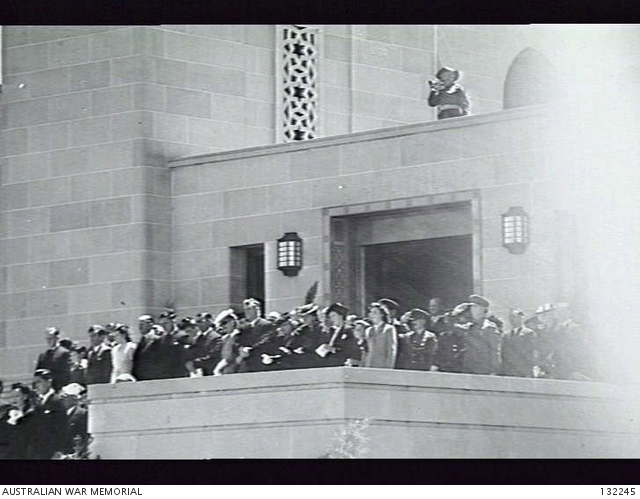

Last Post, first Remembrance Day ceremony, Australian War Memorial 1946 (AWM 132245/DH Wilson)

Last Post, first Remembrance Day ceremony, Australian War Memorial 1946 (AWM 132245/DH Wilson)

I had just spent several weeks trawling the under-floor excavations of churches in Rome. The fact that the inner courtyard of the Memorial has the floorplan of a cathedral – nave and clerestories without a roof – provided a striking similarity. On the day I visited this secular cathedral, crowds of schoolchildren hung over the balconies and filled the courtyard alongside the Pool of Reflection in four long rows, two on each side. The scene reminded me of people leaning over the first floor balustrades of the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, stretching forward into its vast space, glorying in its refinement, its decorations, the scattered rays of sunshine and the bright light streaming in from above. Hagia Sophia was first a Christian basilica, later a mosque, now a museum. It sort of fits.

There must have been hundreds of people at the Memorial in the late summer afternoon sunshine. The atmosphere was hot and close. The schoolkids, many sitting cross-legged on the paving stones in their very short shorts and T-shirts, had laid out their caps on the ground in front of them as instructed. No wriggling or selfies. They were unusually hushed; all their attention was fixed on the goings-on in front of them.

There were also Memorial staff and assorted adults. They were the ones snapping the photos later to be posted on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Flickr. There were the ubiquitous noisy toddlers unable to be pacified. There was a bit of pushing and shoving up the back from people trying to see, with various gatekeepers directing traffic. It was mostly white Anglos attending, but not all.

The formal proceedings began with someone in a suit pronouncing from a formal lectern up the front, way up on the high altar. [2] Next to him, a serving Army officer in uniform, saluting. [3] We were invited to sing only ‘if we were comfortable’ and we started with one verse of the National Anthem. (There was much pandering to what people were ‘comfortable’ with all the way through; the bureaucrats had clearly been in on the drafting. However, no one inquired at any time if we, the congregation, were ‘relaxed’.)

Suddenly, on the steps leading down from the Hall of Memory, there appeared a bagpiper in a kilt and someone with a bugle. It was dramatic, certainly choreographed. Also, it was overwhelmingly male up there on the altar, despite one skirt. Closer to the people, near the pool, was a large photo of a soldier riding a camel, clearly World War I Egypt. The soldier’s family went first and laid their wreath in front of the tripod. They hesitated, then stepped back and bowed their heads. The Army man at the lectern seemed to be outlining the family’s relative’s service, but it was a murmur, impossible at the back to hear the details clearly. Pity.

Next, a youngish Melanesian couple, maybe in their mid to late thirties, laid flowers. Out of the mumbling, the words ‘New Guinea’ seemed to emerge but who were this couple? From the High Commission? A military attaché? A soldier and his wife? A soldier and her husband? Relatives of a PNG citizen who had served in the military? Were they someone or something else? The card on their wreath did not shed any light so we, the congregation, were none the wiser.

All this time, the Memorial Director, Dr Brendan Nelson, was standing stiffly to attention. He tries to attend the ceremony whenever he is in town. Alongside him were people clutching large wreaths. Were these tributes chosen ahead of an early evening aperitif? It was moving in its own political way.

Then someone from a different family laid a wreath for another military remembrance. A man was overcome with emotion. After it was over, he could not tear himself away. He was followed by kids from several primary schools in Victoria. There was no announcement as to which state they came from; you had to know that the names of the schools placed them as coming from the inner suburbs of Melbourne.

One of the children’s wreaths sticks in my mind. The card said, ‘We thank all the Australian soldiers, past and present, who have made our country what it is today’. How exquisitely, how cleverly the Anzac myth is perpetuated as if the whole of time, all of our history, all of those people, all of their efforts, the whole of 1788-1915 and what went before, did not and had not ever existed – or, if it did, there was nothing significant to remark upon.

I wondered if adults had helped the primary kids to write their message and what their motivations were. [4] Was it just a job that both adults and kids had done, by rote, the adults reciting acceptable wording and the kids putting it down? Will getting the Anzac myth imprinted early on the next generation jump over the contrariness of those of us from earlier generations, who tend to see through the myth? Or will these children also eventually put the myth in its proper place, alongside other myths of childhood?

After the Last Post blared out, it was all over. The school kids were promptly marched off to waiting buses. The rest of the crowd dispersed but lingered. You could go up and look at the wreaths before the Pool of Remembrance before they were whisked off for reuse. By close inspection, you noticed that the flowers and foliage were artificial.

The Last Post ceremony concludes (Canberra Times/Melissa Adams)

The Last Post ceremony concludes (Canberra Times/Melissa Adams)

When I left the Memorial about an hour later, only the camel man’s wreath remained in the great expanse of the inner courtyard. [5] Lying alone, frail and fragile on the edge of the pool, it was completely swamped by the lightness of the cathedral’s open air and the heaviness of its dusk. The memory-circle of this wreath was homemade, in sharp contrast to the other tributes. Sprigs of rosemary were stuck in the outer rim, along with some flowers, little fruits and bits of plants sparingly bunched over the foam frame. Although by now the flowers were wilting, they seemed to have been carefully chosen. No one had explained why they had been selected or what they were. Again, a pity.

This homemade effort was all that was left, the sole sign that the ceremony before the altar had actually taken place. The photo on the tripod was gone. The poignancy of this meagre but heartfelt offering had been completely lost in the buzz of the occasion. More pity, it was gold.

I had started by thinking ‘what a waste of taxpayers’ money’. I ended by thinking ‘what a worthy substitute for a national cathedral, without needing to waste the funds’. [6] The Memorial’s courtyard had never struck me before as a basilica without a roof but it did on this day. And we do need the Indigenous gargoyles in the courtyard. We need someones there, not just flora and fauna, to watch over our past in an eternal continuum with the Dreamtime, to act as custodians of memory, to remind the strangely quiet kids in shorts, with their caps laid on the ground in front of them, of what fills their pasts and should inform their futures. How right it is that those someones should be our First People.

Sarah Brasch is National Convener of Women for an Australian Republic.

[1] It is at 4.55pm every day and runs for about 20 minutes, 364 days a year. The Memorial has a comprehensive website about the daily ceremony, featuring guidelines, order of service, FAQs, request forms, etc. There is now a long waiting list for Last Post ceremony slots and events are set down for several months in advance. On some days, there are fixed ceremonies at the Memorial (for example, 11 November) and the Last Post ceremony is not held.

[2] This turned out to be the Master of Ceremonies. No provision for Mistresses of Ceremonies it seems.

[3] Female and male members of the military volunteer to read out the story of the day’s commemorated death. There are over 102 000 war fatalities to date so it is estimated that it will take over 290 years to compete one cycle of commemoration at about 350 per year.

[4] The cards are catalogued and kept in the Memorial’s collection in perpetuity.

[5] This floral tribute was for Lance Corporal William Menadue from Adelaide. Details of each day’s principal commemoration are available on the website but anyone attending can lay a wreath (advise the Memorial by 4pm on the day). Footage from each ceremony is available three to six weeks after the event. Photographs taken by anyone attending can be posted on AWM’s Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or Flickr accounts.

[6] Each day’s Last Post ceremony is live-streamed on the Memorial’s website, available in Australia and overseas, and into selected RSL clubs in NSW and Victoria. The event is ‘proudly supported’ by the RSL and Services Clubs Association, RSL Victoria and RSL Queensland, although what that support entails is not disclosed.

Almost as though” … all of those people, all of their efforts, the whole of 1788-1915 and what went before, did not and had not ever existed – or, if it did, there was nothing significant to remark upon.” Almost as though those who didn’t die in some military action or other had had lives that didn’t signify anything. Just a name, birth date, death date isn’t enough to matter. That is, unless a battle or at least campaign can be attached to the individual’s end. A sad commentary on the way we look at life. You matter if you die young, preferably wearing a uniform, while trying to impose a military solution to some problem that has gone horribly wrong.