‘The well-worn track of commemoration’, Honest History, 23 October 2014

David Stephens reviews Peter Pedersen’s, Anzac Treasures: The Gallipoli Collection of the Australian War Memorial

Anzac Treasures is a great big, complex book, just as the Australian War Memorial is a great big, complex building. The book is a little difficult to characterise – again, rather like the building, which is at once memorial, museum, research centre, theme park and (if one believes its current director – one does not have to) the place where resides the soul of the nation.

The book is too heavy (at two kilos) to be a coffee table book and too lengthy (more than 400 pages) to be a catalogue of the collection it describes. Yet it has elements of both these genres. It also contains competent and sometimes lyrical military history from Dr Pedersen. It is beautifully produced by Murdoch Books with hundreds of photographs, familiar and unfamiliar, some of them foldouts, and expertly printed in China. It is sturdy enough to survive eight months in a Gallipoli dugout. As far as it goes, it is a credit to the publishers and to the Australian War Memorial, whose premier Anzac centenary production it is.

(Copyright in the text and the photographs is held by the Memorial, copyright in the design by Murdoch Books. The undiscounted price of the book is $69.99. It would be interesting to know where the money is going. We asked the Memorial and Murdoch Books about this and both referred us to the other. On the basis of these contacts, though, we understand there is a publishing contract, which presumably includes something in it about payment for intellectual property, preparation work done by Memorial staff, and royalties. Should either party wish to disclose anything further we will, of course, publish it without alteration. We understand that a Question on Notice has been lodged in Senate Estimates.)

As far as it goes … We will come back to that but, first, some basic description. The book has 11 chapters, commencing with an overview of the Dardanelles venture and some notes on how the Gallipoli collection has been put together from 1915 to now, then ten chapters from ‘Off to War’, through ‘Plans’ and ‘The landing’ to ‘Holding on’, ‘Krithia’, ‘Life at Anzac’, ‘The August Offensive’, ‘At home’, ‘Evacuation’ and ‘Aftermath’. There is a foreword from Director Brendan Nelson and another foreword from Ben Roberts-Smith VC MG. The influence of Charles Bean, as collector, chronicler and promoter, permeates the whole volume, as it does the Memorial.

As far as it goes … We will come back to that but, first, some basic description. The book has 11 chapters, commencing with an overview of the Dardanelles venture and some notes on how the Gallipoli collection has been put together from 1915 to now, then ten chapters from ‘Off to War’, through ‘Plans’ and ‘The landing’ to ‘Holding on’, ‘Krithia’, ‘Life at Anzac’, ‘The August Offensive’, ‘At home’, ‘Evacuation’ and ‘Aftermath’. There is a foreword from Director Brendan Nelson and another foreword from Ben Roberts-Smith VC MG. The influence of Charles Bean, as collector, chronicler and promoter, permeates the whole volume, as it does the Memorial.

The book is not easy to absorb. Most readers will dip in rather than plough through. After a couple of false starts, I worked through it from beginning to end, looking only at the pictures and their captions, then read it, chapter by chapter, in reverse. There are diary pages, letters, postcards, periscopes, paintings, medals, scraps of material, maps, models, flags, waterbottles, whistles, rifles, cannons, pistols, bullets, boats, binoculars, bells, barbed wire, bugles, bombs, tins of tobacco and bully beef tins, trenching tools, jangling things on wire, a stuffed horse’s head, a Furphy water tank on wheels, Monash’s stretcher (captured from a Turk), Brudenell White’s desk and pencil, all sorts of souvenirs, recruitment posters, and lots more. The photographs of these objects are great and the production values first-class.

Some of the captions on the illustrations are fascinating, particularly those describing how a prized photograph was lent to the Memorial or its collecting predecessors and copied or how the artefact was donated after being held in the soldier’s family for decades. (There is also the admission that an early topographical model had its vertical scale boosted by 2 to 1, which made the terrain look even more difficult than it was in reality.) Some material, however, will only be of interest to the most well-burnished of military buffs. Some, describing how an object came to look dishevelled due to the impact of a bullet or shrapnel, is frankly ghoulish. When discussing the book and the collection on ABC Radio National Dr Pedersen balked at choosing a favourite object and said they were all equally redolent, all equally poignant.

Let’s look now at the text. The chronological chapters are interspersed with chunks of pages headed ‘Collection items’. So we have, for example, following the chapter on the landing, relics of this event (‘Pompey’ Elliott’s boot, a chunk of shrapnel on a chain, a rusted watch stopped forever at the time the wearer jumped into the water on 25 April 1915) and long descriptive captions. The narrative chapters have plenty of similar material. Rather than being a history, the book is about just what it says on the cover, the Memorial’s huge collection of knick-knacks, relics, trophies, bits and bobs, and records from this crowded eight months a century ago.

Many of these items are no more than curiosities. They tell us little, other than that someone wore this or carried it or wrote it a century ago and here it is now. Even within the chapters proper, the impulse to provide a perfect picture of a relic often trumps informing the reader. There are many reproductions of letters and diary entries in longhand but there are disappointingly few transcriptions. Many readers will not bother to decipher the scrawl. Maybe deciphering isn’t even the point; the letters and diaries just are. Monash’s letter on 24 April to his wife is easy to read, however, and gives a hint of his methodical turn of mind; while Monash lacks the lyricism of Sullivan Ballou on the eve of First Bull Run the letter deserves a place in the Pantheon of battle-eve writing.

Dr Pedersen began the book as an employee of the Memorial and presumably had fairly detailed riding instructions. Whether the structure of the book was his choice or was requested of him, he never really works up a narrative head of steam – a bit like the Dardanelles campaign itself – but still delivers some thoughtful and balanced essays on aspects of the campaign and of Gallipoli life, such as his comparisons of Generals Bridges and Birdwood and of Albert Jacka VC and John Simpson Kirkpatrick, his pages about soldiers’ ‘final thoughts’, his descriptions of the time in Egypt, the truce of 24 May and nurses on Lemnos, and his section on how The Anzac Book was put together. His discussion of how Sidney Nolan came to produce his Gallipoli paintings is excellent also, as is his sketch in chapter 11 of the early construction of the Anzac legend.

The episodic style works well enough once you realise that the text is subsidiary to the pictures, which are the real highlight of the book. Apart from the illustrations of icons referred to above, the photographs range from close-ups of haggard figures huddled in trenches to images of jumbled gatherings of men (sometimes swimming) and boxes of stores on the beach at Anzac Cove, to panoramas of the bare hillsides. (Peter Stanley has written elsewhere of how different today’s vegetated gullies look and of the risk of bushfire they pose.)

There are very few pictures of dead soldiers but this reflects the protocols of the time; there were not many such pictures taken. There are a few descriptions of bloody deaths and injuries but the portrayal of the 8709 Australian Gallipoli dead and 17 924 wounded is mostly left to some pages in chapter 7 on wounds and illness, George Lambert’s paintings and Wallace Anderson and Louis McCubbin’s Lone Pine diorama. (Someone, sometime should write a piece psychoanalysing Australians’ attitudes to war dioramas and panoramic paintings of ‘patriotic gore’; is ‘war pornography’ too harsh a description of this genre?)

There are no confronting photographs either of severely wounded men; this is another departure from reality. A great-uncle of mine had his legs blown off swimming in Anzac Cove in July. (‘The beach’ is described in chapter 7.) Another great-uncle had his arm blown away throwing bombs at Hill 60 at the end of August. Both died and were buried at sea. One can only imagine what they went through in their last hours. Anzac Treasures is as unhelpful in this regard as the ‘he died like a Briton’ letters that both families received. An honest war history collection, as distinct from one about military history, would depict the effect of these deaths on families down the generations – the Dead Man’s Penny for one of these great-uncles was handed on to me with some ceremony when I was about 12 years old – as well as the lives after the war of ‘the legless, the armless, the blind, the insane’ and of their loved ones.

Which brings us back to ‘as far it goes’. Anzac Treasures reflects the limitations of the Memorial itself. The book traverses well-ploughed ground; it is intensely conservative. Apart from the inclusion of relics donated in recent years, the book could have been published 50 years ago. We have more evidence now of what actually happened at Gallipoli but what the Memorial has done with that evidence is little changed. It is still obsessed with what Australians have done in war, to a far lesser extent with what war has done to Australians, and hardly at all with why we have fought ‘our’ wars and whether they were worth it, let alone with their broader context. Hugh White was critical of Les Carlyon in The Great War for spending only half a page out of 800 on why Australia committed to war in 1914. (Carlyon has recently been reappointed to the Memorial Council.) Anzac Treasures has barely a sentence on this subject. It faithfully reflects the Memorial’s eschewing of the hard questions.

The sentimentality that led Dr Pedersen to place all the relics on an equal footing pervades the book: everything has a connection to this time in our history therefore everything is equally worthy. ‘The tragedy symbolised by a shrapnel-torn scrap of uniform found on the battlefield’, agrees Director Nelson in his foreword, ‘is no less powerful than the reverence evoked by two of the boats from which the Australians landed on that first Anzac Day’. Leaving aside the loaded word ‘reverence’, the very title of the book – Anzac Treasures – is significant: the items in the collection are treated in the same way that the contents of The Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg are or those of the National Archaeological Museum in Athens or the Relics of the True Cross. All of them are handled with metaphorical white gloves.

It is easy to see why the Memorial does this, in relation to Gallipoli and to our military history generally. It does it because it can. It has a seemingly endless supply of material, 8000 photographs of Gallipoli alone, thousands of unit and individual diaries, 400 maps of Gallipoli, 6800 trade cards (cigarette cards and such with little stories about war), 10 000 posters, and so on. Every new discovery, like the Vignacourt photographs or the Fromelles bodies, gives a boost to the traditional approach. There is no need to broaden the perspective from military history to war history when there is so much military history to publicise and promote. (The ‘At home’ chapter in the book is mostly about how the war was reported in Australia, comforts funds, recruiting posters and patriotic souvenirs; nothing about division, growing disillusionment and industrial upheaval. The ‘Aftermath’ chapter is about the crafting of the Anzac legend; nothing about disfiguring wounds, PTSD, influenza epidemic, post-war social conflicts, soldier settlers being let down by government, shattered and grieving families, pervasive sadness and sense of loss.)

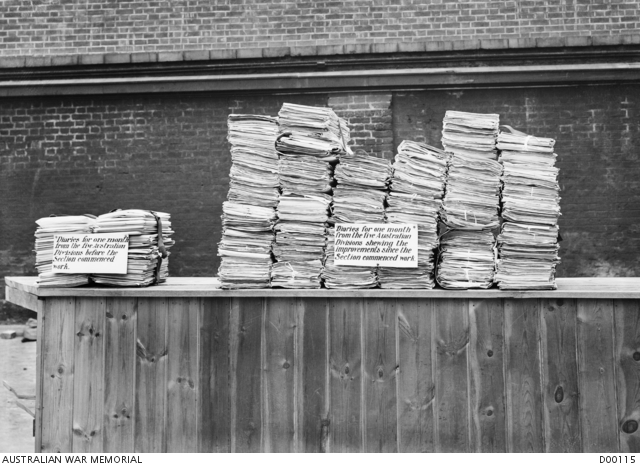

Illustrates the effectiveness of the Australian War Records Section, the collecting agency established in 1917 under John Treloar, later director of the Memorial. Each pile is a month’s worth of records but the pile on the right is bulked up by the inclusion of additional documents as well as unit diaries. Photo c. 1918 (AWM D00115)

Illustrates the effectiveness of the Australian War Records Section, the collecting agency established in 1917 under John Treloar, later director of the Memorial. Each pile is a month’s worth of records but the pile on the right is bulked up by the inclusion of additional documents as well as unit diaries. Photo c. 1918 (AWM D00115)

Yet the scope is there for a more comprehensive approach. The Memorial’s Act allows it to be more adventurous, despite the narrow interpretation the Act has been given by the Memorial in recent decades. The words in the Act effectively give the Memorial a remit to look at why we fought our wars, who we fought them against, what other belligerent countries did and what happened at home and afterwards.[1] The Memorial should be looking at all of this in at least as much detail as it devotes to what blokes in khaki under orders did to men from other countries also fighting under orders.

There is at the Memorial a lively senior management group, led by a Director who has great marketing skills and who would have a reasonable chance of taking his Council in a new direction. (The Memorial’s narrow current brief presumably came about because of similar interactions between previous Directors and Councils.) There is also a service and ex-service constituency which is gradually losing its aging Anglo-Celtic cadre and showing signs of uneasiness in its younger ranks at the continual promotion of the image of Anzac superheroes striding through the ages – a promotion which the Memorial contributes to in spades. There are committed, imaginative and expert curators, most of them from the post-Vietnam War generation rather than the post-World War II era, who might thrive under some new rules of engagement.

There is, all in all, an opportunity for an Australian War Memorial to develop which is different from the military reliquarium which emerges from the pages of Anzac Treasures. It may be the world’s leading such institution – as well as being an excellent research facility and, for the most part, a dignified locus of commemoration – but it could be so much more and, in doing so, could be so much more relevant to the Australia of the future.

This Australia might, if we are lucky, be one which, in Hugh White’s terms, thinks less about how it fights and more about why it fights, one which is more prepared to question the links between particular fights and our national interest and human worth, one which is less tolerant of the sentimentality regarding war which suffuses Anzac Treasures. ‘Sentimentality distances and fetishizes its object; it is the natural ally of jingoism’, says Elizabeth Samet, a lecturer at the United States Military Academy, West Point. ‘So long as we indulge it, we remain incapable of debating the merits of war without being charged with diminishing those who fought it.’

The historian of the RAAF, Alan Stephens (no relation) recently reviewed the Memorial’s Afghanistan Voices exhibition and found that, while it told the story of what Australians did in that war, it did not examine why we went there and what it meant to our nation. Political context was lacking. The exhibition was also misleading because it avoided the ‘unfathomable depravity’ of war and played up civil and training programs which were doomed to fail.

This criticism goes to the heart of what the Memorial does: wittingly or unwittingly, it sells people short. ‘Every year’, says Alan Stephens, ‘hundreds of thousands of Australians gain their basic understanding of war from visiting the Australian War Memorial. Regrettably, by telling them only half the story, the Memorial is failing in its responsibility’. People have been only too willing to be sold short, of course, not only by the Memorial but by the other purveyors of sanitised and sentimentalised military history. Pedersen includes a telling quote from Brian Lewis, recalling his childhood at the time of Gallipoli. Inspired by the dispatches of Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, boys of the time day-dreamed of ‘lines of men charging forward with fixed bayonets with astonishing heroism’. The image ‘was fixed in our minds and was never replaced when the real facts filtered back’.

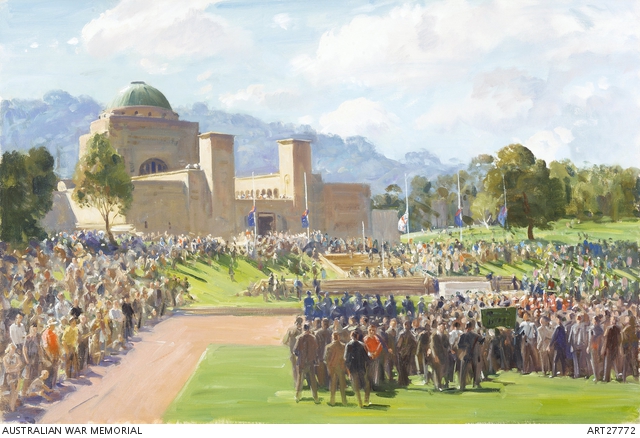

Anzac Day ceremony, Australian War Memorial, 1971 (AWM ART27772/William Dargie)

Anzac Day ceremony, Australian War Memorial, 1971 (AWM ART27772/William Dargie)

Anzac Treasures is about rather more than bayonet charges. It attests above all to the stoicism of ordinary men in impossible circumstances. There is, however, much more that can and should be said about Gallipoli and about war than is said in this book. With due respect to Allen and Unwin’s blurb writer, while the ‘legend’ of Anzac may haunt the book, much of the ‘reality’ has to be sought elsewhere. With the centenary of Anzac turning a sharp focus towards the wars Australia has fought, perhaps Australians will look for more from their War Memorial than it has given them thus far. After a century, it is surely time to move on from Bean’s vision of the Memorial as ‘the finest monument ever raised to any army’.

David Stephens is secretary of Honest History. In 2011-13 he and others were active in opposing the construction in Canberra of new memorials to the World Wars, partly because they would have detracted from the Australian War Memorial.

[1] The Memorial’s Collection Development Plan under ‘First World War 1914-18: Historical background’ has 10 paragraphs on aspects of the fighting and one paragraph on home front and aftermath. The section ‘Collecting aims and priorities’ for this war reveals: good representation of all major battles, though could do better on Bullecourt; strong on captured enemy equipment though need more Australian kit; some weaknesses on military heraldry and memorabilia of leaders and personalities; could do with more naval pictures and pictures of people on commemorative rolls; more art needed on naval and air service and women’s service and involvement. ‘The home-front part of the collection needs particular strengthening, especially in the area related to the two conscription referenda.’ Finally, there are strengths in official records, letters and diaries and published works and collections, including cigarette cards.

“It is still obsessed with what Australians have done in war, to a far lesser extent with what war has done to Australians, and hardly at all with why we have fought ‘our’ wars and whether they were worth it, let alone with their broader context.” The war memorial in a nutshell. A wonderful institution, though flawed in its focus.