‘Two views of World War I: sight-bites and Keepsakes‘, Honest History, 3 February 2015

David Stephens reviews the refurbished World War I galleries at the Australian War Memorial and the Keepsakes exhibition at the National Library of Australia. (A further article written after the ‘hard launch’ of the refurbished galleries on 22 February.)

Not long after Dr Brendan Nelson became Director of the Australian War Memorial he talked to his fellow national cultural institution heads about how, between them, they should mark the centenary of the Great War. He said that the Memorial alone could not properly portray what Australia was like a century ago and that the National Library, the National Museum, the Museum of Australian Democracy and other institutions needed to do their bit, too. ‘[N]ecessarily’, Dr Nelson said, ‘almost all of what we will represent at the Australian War Memorial will be the military engagements in which we were involved’.

Dioramas return with knobs on

The Memorial’s re-opened World War I galleries bear out Dr Nelson’s remarks. (The ‘soft launch’ was on 1 December; the official opening will be later in February.) Military engagements are still front and centre, but more shiny. Charles Bean’s vision is still dominant, even if in new clothes. This is still ‘the finest monument ever raised to any army’ but it is still trophy room as well as shrine. On the three days we were there (twice in December, once in January) the numbers were running heavily in favour of the World War I galleries, the newest part of the trophy room, compared with the almost deserted Roll of Honour cloisters, the heart of the shrine, and the Hall of Memory. On our January visit, too, the galleries containing the thought-provoking Afghanistan-related art of Ben Quilty and Alex Seton were virtually empty, while visitors thronged the World War I galleries upstairs.

Conserving the dioramas (Australian War Memorial)

Conserving the dioramas (Australian War Memorial)

Veterans of the old World War I galleries will find few surprises in the new galleries. The trusty dioramas still turn soldiers into toys and death-dealing battles into freeze-frames. Now, though, the dioramas and other exhibits have touch panels which bring up gobbets of information. The majority of visitors on the crowded January day seemed content, however, to look at the exhibits without exploring further via the panels. Perhaps this was because of the crowds – duplicate panels would have made access easier – but it had been much the same in December when fewer people were around.

The main feature of the galleries continues to be the battle dioramas (Lone Pine, Pozieres, Dernancourt, and so on). The Pozieres diorama is accompanied by a sustained tutorial on the dangers of trench foot, reflecting the muddy moonscape depicted, and the need for supplies of socks from home. The typical description, though, is standard battle-speak (charges, feints, manoeuvres, and so on) with casualty numbers discreetly tucked in at the end. Some descriptions even mention non-Australian casualties. As in the old galleries, there is a small panel tallying total deaths in the Dardanelles campaign, reminding us that it was not just (or even mainly) an Australian show.

Some of the quotes from soldiers’ diaries and letters home evoke pity, others are just bloodthirsty. Throughout the galleries there are dozens of photographs of soldiers, grouped together like pages removed from family albums, with names and brief biodata accessible at the touch of a button. Some men seem very young. There are little movies, too, some no more than scans of the static items in the exhibit, others cleverly interspersed with stills to illustrate ‘The Light Horsemen’ or ‘Supporting the troops’ and so on. These short presentations are a highlight and it is worth waiting for your turn at the touch panel to work through them. More captions would have been good.

There are high-tech aerial maps of Gallipoli, though they were treated warily by most visitors on the days we went in December. In January, however, there was an attentive cluster of visitors around a volunteer who was explaining how the exhibit worked. A simple ‘how-to’ panel would help with this exhibit and with others where pressing of buttons is involved. Older visitors do not necessarily appreciate that the information or picture on display can be moved on by touching the little arrow on the screen.

John Croft’s pocket book was pierced by a Turkish bullet on Gallipoli on 25 April 1915 (Australian War Memorial PR03842)

John Croft’s pocket book was pierced by a Turkish bullet on Gallipoli on 25 April 1915 (Australian War Memorial PR03842)

Most of this amounts to better ways of imparting the same story, the story that Bean and John Treloar and other giants dedicated themselves to telling. Yet we were promised more. Eighteen months ago, Dr Nelson said of the refurbishment:

We will also present a picture of Australia in 1914 and who we were, why we engaged and embraced the war so readily. We will touch on the deep political and social divisions within Australia through the period of the First World War and give those who come to the gallery the sense of us emerging from it.

More about the way we were?

When the new galleries were opened, we were told they would ‘give more time to 1914 so before you even hit April 25, 1915, we spend time talking about Australia as a nation’. In fact, in the new arrangement there is no more than a paragraph on Australian society in 1914 plus some material on the pre-war military training scheme and the founding of the Royal Australian Navy. These items are overshadowed by a massive boat that landed at Gallipoli, an oversize post-Gallipoli recruitment poster and an even larger display case containing a collection of miscellaneous items, ranging from boots to gas-masks to what look like Vietnam-era American football helmets.

These uncaptioned objects seem to be meant to speak for themselves. When we visited in December a volunteer guide launched into his well-rehearsed spiel – ‘There are 80 000 individual items in the Memorial’ – then it’s German New Guinea, the Emden and the First Convoy and away we go on the Great War Tour (through the new galleries containing about 1600 items, I was informed by another guide). Visitors trail around looking at objects and relics and icons worthy of a medieval shrine to a collection of saints. (See also a review of the Memorial’s recent book, Anzac Treasures.)

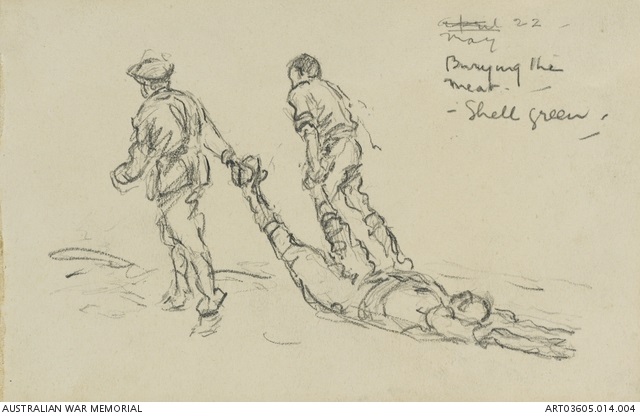

So the trophy room is also a reliquarium. It is an armoury, too. Almost the first display case you see as you walk in contains a machine gun. Next to it is a large shell, highly polished. Near the Pozieres diorama there is a massive cabinet full of ordnance of all sorts and sizes, along with technical descriptions, including a passing admission that some of these weapons could blow men to bits. As to that, although there are more dead bodies shown here and there in the galleries (notably beneath the Lone Pine diorama and in the scrolling collection of photographs nearby) than perhaps has been usual at the Memorial, there is minimal attention paid to the damaged survivors. There is no sustained attempt to show bodies shattered or minds destroyed; ‘casualties’ get a small exhibit in the medical services display and a series of photographs of a reasonably successful facial reconstruction.

Burying the meat, Shell Green, Gallipoli, May, 1915 (Australian War Memorial ART03605.014.004)

Burying the meat, Shell Green, Gallipoli, May, 1915 (Australian War Memorial ART03605.014.004)

Looking for the context

This last series is in the small chamber devoted to the end of the war and the aftermath. This chamber is slightly larger than the equivalent space in the old galleries and not hidden away as before. It is, however, a relatively dimly-lit section leading to a final room which draws the attention with brighter lighting and ethereal music, including a mournful, tear-inducing version of Waltzing Matilda. (Perhaps the architecture is meant to be symbolic – the ‘emerging’ that Dr Nelson referred to.) Beneath Winged Victory in this penultimate room, we are told that Australians after the war enjoyed ‘victory but little sense of triumph’, dealt with grief and suffering but felt pride ‘and a confidence about [Australia’s] place in the world’. A reading of sources about the bruised and grieving Australia of the 1920s (Beaumont, Keneally, Lake, McMullin, and the references tagged ‘Themes-Australia’s war history-Aftermath’ on the Honest History website) would lead one to modify this summary.

Yet, if war history is partly about what happened afterwards, it is also about what happened to others. In this regard, the Turks get a uniformed manikin and a large photograph, there are allusions to British soldiers and French civilians, there are some uniforms associated with Sarajevo and there is the panel listing all Dardanelles casualties. Ataturk’s ‘speech’ to Anzac mothers is recited by a BBC-style voice. (In reality, the speech was probably written by Ataturk but delivered by one of his ministers to a visiting British delegation.) Talking of the Turks, one volunteer guide hit the nail on the head, speaking to his group. ‘We lost. Do you know why we lost? Because we were invading their country.’

Despite these concessions the galleries are still mostly about Australia’s Great War and about only part of it at that. Combining shrine, trophy room, reliquarium and armoury still only tells some of the story. This is what the Memorial does with all our wars. ‘Every year’, says Alan Stephens, ‘hundreds of thousands of Australians gain their basic understanding of war from visiting the Australian War Memorial. Regrettably, by telling them only half the story, the Memorial is failing in its responsibility.’

‘If truth is the first victim of war’, James Rose wrote of the Memorial in 2013, ‘then perhaps context is the first casualty of its memory’. Courage, drama, family connections, grief, hardship, nostalgia, pathos and sentiment are all over the Memorial in spades but rarely are there questions asked, seldom are there conclusions drawn, except those arguable words nestling beneath Victory’s wings. The Memorial is almost all about ‘what?’ and ‘how?’ rather than ‘why?’ and ‘was it worth it?’ and ‘under what circumstances might we do it again?’ An honest record of a nation’s wars should be about not only what a minority of its citizens do on the battlefield but also about what the war does to those citizens and their families, at the time and for generations after, and what it does to the nation.

The refurbished World War I galleries dodge these questions, as does the Memorial as a whole. The two minute video in the final room, with haunting music and captions from Advance Australia Fair, misses an opportunity to leave the visitor with questions. Instead, we get Anzac Day marchers in the 1950s and touching grandfather-grandson portraits, presumably meant to say something about the torch passing between the generations. The final thing we see is the misleading and hyperbolic slogan, ‘Every nation has its story. This is ours’, which Director Nelson also intones as the voice-over talent in an advertisement for the galleries showing in Canberra theatres just ahead of Russell Crowe’s Gallipoli movie, The Water Diviner. Exaggeration is the enemy of honesty just as sentimentality is the ally of jingoism.

South of the Lake

What about the National Library? How has it gone about delivering on whatever was agreed between the cultural institutions 18 months ago? In size alone, Keepsakes, subtitled Australians and the Great War, is hardly comparable with the revamped World War I galleries: the exhibition’s floor area is many times smaller than the galleries. But size is not the only consideration. There is depth and breadth also.

The opening panel of Keepsakes is reminiscent of the guide at the Memorial and his 80 000 items: as memories fade and people die, ‘[t]o understand what they went through, we need to turn to the things they left’. The difference is that the Library’s ‘relics’ are books, diaries, letters, manuscripts, photographs, posters – often complex items requiring thought, items which, if thought about, can give a deeper appreciation of the nature of war. There is in Keepsakes hardly an old boot or a stopped watch or a uniform with bullet holes or a gasmask to be seen.

The focus on written material means that the visitor to Keepsakes needs to spend more time and devote more mental energy to what is on offer. There are fewer ‘sight-bites’ than at the Memorial but there is, if one persists, more engagement and more empathy – and smaller crowds to hamper the searcher after enlightenment. (The Memorial’s visitor numbers have gone up considerably since the refurbished galleries opened.)

Perhaps the fairer comparison is between Keepsakes and the Memorial’s Research Centre, which also has masses of printed and graphic material and fewer people. But Dr Nelson’s vision of complementary Great War offerings from the national cultural institutions needs to be tested and it is the refurbished galleries that he has promoted as the Memorial’s Anzac flagship. Those who prefer a sentimental skim with a khaki hue, artillery and machine gun sound effects, and a bit more detail if they can be bothered, will punt for the Memorial; those who need or want to go deeper and wider and like to keep the military exploits in perspective will prefer Keepsakes.

Keepsakes promotion: Wedding portrait of Kate McLeod and George Searle of Coogee, Sydney, 1915 (James C. Cruden)

Keepsakes promotion: Wedding portrait of Kate McLeod and George Searle of Coogee, Sydney, 1915 (James C. Cruden)

Going deeper

Keepsakes, unlike the World War I galleries, makes a genuine stab at a rounded war history, getting beyond the fate of brave blokes in khaki to look at the conscription battles (complete with a picture of the Melbourne Trades Hall in full ‘No’ campaign regalia), war loans campaigns and internment of enemy aliens at Holsworthy, a particular nasty part of our Great War. There is a letter from an Industrial Worker of the World, intercepted by the censor and then apparently souvenired by Prime Minister Hughes. The caption on this case, ‘A wartime police state’, is apt. (The Library’s captions are easy to read, by the way; its curators have done a better job than the Memorial’s at balancing light restrictions and legibility.)

Always in Keepsakes it is the written material that repays attention. There are sketchbooks and autograph albums, scrapbooks and telegrams, Keith Murdoch’s despatches, Governor-General Munro Ferguson’s diary and letters about whether Monash should become Corps Commander in 1918. There is General Bridges writing to Munro Ferguson from Mudros on 21 April 1915: ‘our great day is to be St. George’s Day [23 April – there was a delay] – if the weather permits … It is going to be a cold, hungry and thirsty business.’ Then there is Percy Deane, later Hughes’s private secretary, titillated but appalled by Cairo, 1915. ‘Practically every native who spoke to us offered to sell “smutty postcards” or guide us to a kan kan dance.’

Prime Minister Hughes, Keith Murdoch, Picardie, France, 3 July 1918 (Australian War Memorial E02650)

Prime Minister Hughes, Keith Murdoch, Picardie, France, 3 July 1918 (Australian War Memorial E02650)

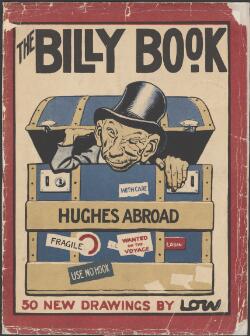

There are dozens of maps, posters and cartoons. Stan Cross (a cartoon of a rather daring bathing beauty), Will Dyson (three beautifully-posed horses and riders in France, 1918), Norman Lindsay (slavering Huns), David Low and others feature, with Low’s skewering of Hughes the highlight. There are a couple of May Gibbs gumnut baby postcards. The posters are mostly familiar apart from one (not by Lindsay), worded ‘Always Huns – AD 451, 1915. Protect our women and children; join the Australian Army’, which adds to the folklore about the allegedly vicious enemy.

The Library makes better use of large writing on walls than does the Memorial. There is a useful timeline with events well-distributed between Australia, Australian exploits overseas, and international context, plus a collage of newspaper headlines, posters, cartoons, and information about total war casualties – not just Australian and not just service – and a reminder that the influenza pandemic of 1919 took more lives than the war itself. (Keepsakes could have said more about the aftermath of war.) Speaking of writing, where Charles Bean’s ‘Here is their spirit’ remark looms over the entrance to the refurbished War Memorial galleries, Bean in Keepsakes occupies just one small case, though the case does include some of his books, annotated in his hand.

The Keepsakes static exhibition is accompanied by an essay from curator Dr Guy Hansen, links to some relevant collections of papers, including those of Hughes, Monash and Murdoch, and a 20 minute oral history and illustrations compilation, with interviews in 1980 of Australian and British airmen, with Alec Campbell, ‘the last Anzac’ (interviewed 2001), and descendants (interviewed 2008) of Soldier Settlement farmers. The brief snippets from the airmen mostly describe operations and close shaves. Campbell, however, is reflective and philosophical about life at Gallipoli and briefly touches on the reasons why people fought.

I suppose that we had some sort of an idea that it was to protect Australia and, in a way, England, because we used to think a lot more of England in those days than we do now, because we hadn’t seen so much of it, I suppose.

The Soldier Settlement illustrations are fascinating and give an idea of the harsh lives led by many of these families, often on blocks that were too small to be consistently viable.

Cover of book of cartoons by David Low, 1918 (National Library of Australia)

Cover of book of cartoons by David Low, 1918 (National Library of Australia)

Summing up

Whether visitors undertaking a Great War tour of Canberra in the next four years get a rounded view of Australia 1914-18 will depend on what exhibitions are on when the visitors get here. At the time of writing (January 2015) they can see the new World War I galleries and Keepsakes. But Keepsakes ends in July 2015. The Memorial is here all the time; it portrays war constantly. Its partial view of war – the half-story that Alan Stephens referred to – is the one that most people, including children, will take home to Penrith and Perth, Wagga, Wanniassa and Wollongong.

The Memorial is partial, not only because it tells just part of the story, but also because it soft-peddles the ugly bits of what is left, sepia-toning the blood-red and putrid. It takes one side, when it should show all sides. The lack of exhibits depicting death, injury and mental illness from combat is partly because delicacy and politics at the time limited the amount of raw material in this genre. Those constraints persist but the Memorial still fails to make enough of the resources it has in these fields. It could and should run exhibitions on wounds and mental trauma sustained in the Great War and all our other wars. (The British National Army Museum had such an exhibition nearly a decade ago.)

More important though, given Dr Nelson’s 2013 statement, is the Memorial’s avoidance of events on the Great War home front and after the war, including what happened to the 208 000 servicemen who had been hospitalised, 30 per cent of them with ‘shell shock’. The other national cultural institutions can temporarily put the Great War into context, as the National Library has done with Keepsakes. The Memorial itself might occasionally modify its wonted khaki tinge, as it did with Of Love and War 2009-10. It is unrealistic, though, to expect the other cultural institutions to consistently cover for the Memorial’s failure to present a balanced view of our war history. This should be the Memorial’s job; it could do it without violence to its legislative charter. (The words in the Memorial’s Act allow the Memorial to look at why we fought our wars, who we fought them against, what other belligerent countries did and what happened at home and afterwards.) It could start by working up an exhibition based on the post-war Repatriation files, now becoming available.

Finally, we need to ask whether the Memorial, by sentimentalising and sanitising war and by avoiding looking in depth at the reasons behind and the effects of our military involvements – the Afghanistan exhibition is a recent notable example – effectively contributes to the perpetuation of a bellicose Australian culture, particularly among children, and thus to the continuation of those involvements. ‘Despite an apparent endeavour to not celebrate victory’, James Rose has written, ‘the War Memorial can be guilty of celebrating – or at least assuming the necessity of – the act of war itself’. In the case of children, ‘[i]t’s hard not to see it as a kind of imprinting’. As well as shrine, trophy room, reliquarium and armoury, is the Memorial also jingoistic urger and military recruiting office?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.