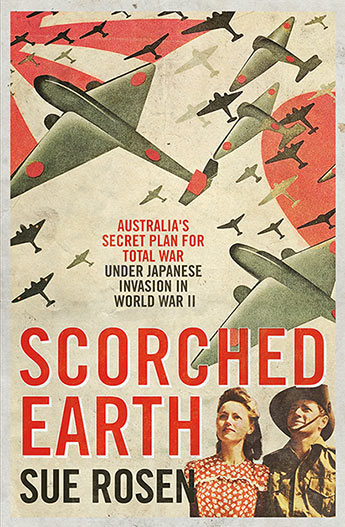

‘Scorched earth flames are fanned again’, Honest History, 13 June 2017

Derek Abbott* reviews Sue Rosen’s Scorched Earth: Australia’s Secret Plan for Total War under Japanese Invasion in World War II

The reality of the threat of a Japanese invasion of the Australian mainland in 1942 has been much debated: was Australia to be occupied in whole or in part, cowed by local attacks on targets of strategic significance or isolated and left to wither? The consensus appears to be that, while an invasion was considered by some Japanese staff officers carried away by the apparent ease of her early victories, it was not given serious consideration at the highest levels. However, as Imperial Japan swept from victory to victory in late 1941 and the early months of 1942 and the façade of British power in the east collapsed, Australian fear of the threat of invasion was both real and rational.

The reality of the threat of a Japanese invasion of the Australian mainland in 1942 has been much debated: was Australia to be occupied in whole or in part, cowed by local attacks on targets of strategic significance or isolated and left to wither? The consensus appears to be that, while an invasion was considered by some Japanese staff officers carried away by the apparent ease of her early victories, it was not given serious consideration at the highest levels. However, as Imperial Japan swept from victory to victory in late 1941 and the early months of 1942 and the façade of British power in the east collapsed, Australian fear of the threat of invasion was both real and rational.

The documents that comprise the bulk of this book are testimony to the extent of that fear. They give a valuable insight into some elements of the strategic and tactical thinking about how a Japanese invasion might be resisted. Scorched Earth consists of a document prepared by EHF Swain, New South Wales Forestry Commissioner, for Premier William McKell in January 1942, plus a series of documents comprising the NSW Scorched Earth Code, reproduced in their entirety, as well as short introductory comments by the author on each of these documents.

The Code was prepared by a sub-committee of the State War Effort Co-ordination Committee – of which Swain was Chairman – in response to a request from the Commonwealth for all states to prepare such plans. Swain is described as a forceful character, of prodigious organising ability with a passion for civil defence. These qualities are clearly apparent in the paper he sent to McKell in January 1942 entitled Total War – and Total Citizen Collaboration, which comprises chapter one of this book.

Swain’s paper is both a call to arms and a first draft of a plan for civil mobilisation (and perhaps a job application). Swain reveals some knowledge of the conduct of the war and draws on that to both predict the course of an invasion and the appropriate response to it. On the other hand, his descriptions of Russians luring the German Army on or that the Chinese ‘in their millions, and mostly afoot, jog trotted over three thousand miles of dirt tracks to a New China in Chungking’ suggests a somewhat idealised view of those campaigns.

Swain rails against complacency and the ‘it can’t happen here’ mentality, painting a gruesome (and probably accurate) picture of the likely behaviour of Japanese troops who, as he notes, ‘will not forget the White Australia policy’. He exhorts Australians to ‘slaughter the armed “yellow dwarfs” with our own “tooth and claw” in our own familiar forests’.

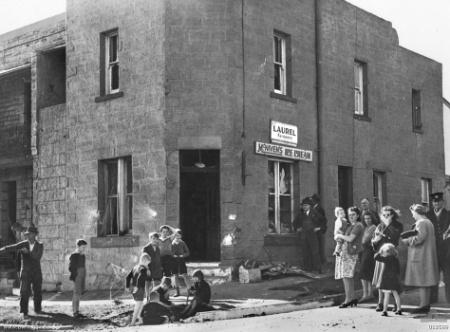

Woollahra, Sydney, damage from Japanese shells, June 1942 (Wikipedia/AWM)

Woollahra, Sydney, damage from Japanese shells, June 1942 (Wikipedia/AWM)

Swain saw Brisbane, Sydney, Newcastle, Melbourne and Canberra as ‘our Leningrads and Moscows’ from which there could be no retreat. Experience in Europe and at Penang (where cities were abandoned to the enemy with their infrastructure and productive capacities more or less intact) weighs on Swain as he demands a plan that ‘must be one neither of evacuation nor of staying put; but one of organised military-civil defence-in-depth’. His paper then goes into detail on how such defence-in-depth is to be organised, identifying routes for withdrawal into the hinterland, the rations an individual should carry and of the duties of every occupation to maintain production while identifying those assets that must be moved or destroyed should withdrawal be necessary.

Subsequent chapters comprise the detailed plans prepared by the Scorched Earth Sub-Committee and exhibit the same impressive attention to detail apparent in Swain’s original paper. For example, ocean jetties and estuary wharves along the New South Wales coast are listed and the latter are classified in terms of their usefulness to an enemy – the depth of water, access, load capacity and condition. The agency that would be responsible for their demolition is also identified. Similarly for petroleum supplies, there is an extensive list of wholesale suppliers and a description of the various means by which fuel supplies could be destroyed or rendered useless. This level of detail is repeated in sections dealing with motor vehicles, watercraft, coal mines and public utilities. A General Citizen Code and a General Industry Code provide similar advice for the individual and industry.

As a paper exercise, the Plan is a testament to the energy and thoroughness of its authors. What this book lacks, however, is any real attempt to put the Plan into context, to examine how seriously it was taken by government and the military and to consider its practicality. Given the level of detail and total mobilisation that the Plan foreshadowed its implementation would have required a remarkable effort by the civil and military authorities – and what we now call civil society – to have had any chance of success; in particular, the projected active resistance to the Japanese presupposes a high level of civilian morale. Swain himself acknowledged that the Japanese had been preparing for total war since 1915; ‘We have a day, a week or a month perhaps’. Fortunately, Australia never had to find out.

Michael McKernan’s study of the home front, Australia during the Second World War: All In!, first published more than 30 years ago, looked at the NSW Scorched Earth Operational Plan, presumably the same document. McKernan noted that the Army insisted on retaining control of actual decision-making with regard to the implementation of any scorched earth plans. The Chairman of the Scorched Earth Committee – presumably Swain though McKernan is not explicit – wrote that he ‘view[ed] with extreme disquiet this lack of positive action’.

More generally, McKernan notes that the Government and the military were extremely wary of popular movements and vigilante groups. He also comments on the ‘mood of panic’ that gripped the country when, ‘In the hectic weeks after the fall of Singapore all kinds of wonderful plans were formulated, including scorched earth, civilian evacuation and the concentration of defence in some key areas’.

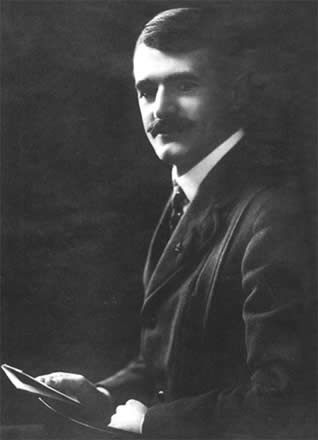

Swain before the war (Forestry in Queensland)

Swain before the war (Forestry in Queensland)

France 1940, the early months of Operation Barbarossa and the fall of Malaya clearly demonstrated that morale is a significant factor in resisting invasion. The total war mobilisation of the civilian population that the Scorched Earth Plan envisaged – including the risks of guerrilla warfare and the abandonment and destruction of people’s own property and livelihoods – would have required very high morale and unity of purpose to be effective. Yet for most of the war, government remained concerned that the civilian population were not taking it seriously enough. AP Elkin, a Sydney academic, who attempted to replicate in a small way Britain’s Mass Observation and gauge public opinion systematically, wrote repeatedly to Curtin warning of the poor state of public morale, noting that talk of scorched earth and mass evacuation encouraged defeatism.

As Sue Rosen mentions, Swain’s entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography doesn’t mention his responsibility for the Scorched Earth Plan. Beyond Swain’s prodigious capacity for hard work we know little about his qualifications to comment on military matters. Much of the exhortation in his first paper exhibits what the ADB describes as his capacity for ‘impassioned speeches and polemics’ rather than a practical grasp of military realities.

Was Swain an energetic armchair strategist who irritated a military already overstretched and undermanned or was he a respected and influential voice? Some of the documents included in this book are dated mid-November 1942. By then any plausible threat of invasion of the Australian mainland had passed, with Allied victories in the Coral Sea and at Midway in May and June and the Japanese in retreat in New Guinea from late September. Was the Scorched Earth Committee’s continued activity at that stage an indication of Swain’s energy rather an urgent need for its output?

It is always welcome when historical documents are made more accessible to scholars and the general public. It is difficult, however, not to view this book as a missed opportunity for a detailed examination of the response to the perceived threat of a Japanese assault on Australia in the early months of 1942.

In the spirit of Honest History’s hostility to myths it should be noted that the publishers have used a quote from another author to promote Scorched Earth: ‘Arguments over the Brisbane Line are settled here’. The book does nothing of the sort. The Plan’s focus on the defence of the major population and industrial centres of New South Wales is consistent with a military appreciation by the GOC Home Forces, Lieutenant-General Mackay, in February 1942 that forces be concentrated in those areas ‘vital for the continuance of the war effort’. The Curtin government rejected any intention to abandon any part of Australia.

Eddie Ward in later years (Wikipedia)

Eddie Ward in later years (Wikipedia)

Mackay’s appreciation may have formed the basis for the ‘Brisbane Line’ accusation that Labor firebrand Eddie Ward used for purely partisan purposes in an attempt to label Menzies and Fadden as defeatists, willing to surrender vast areas of the country and its people to the Japanese. Ward’s claim was found to be groundless by a Royal Commission during the war and was dealt with in Hasluck’s The Government and the People, 1942-1945. Nevertheless, it has taken on a life of its own in the intervening years. It is a pity to see it given a kick along here.

* Derek Abbott is a retired parliamentary officer. He has previously reviewed books for Honest History on The Silk Roads, Victor Trumper, sport, Australian foreign policy, World War I at home, Duchene/Hargraves and the discovery of gold, and other subjects.

D. Abbott should try to read Drew Cottle, The Brisbane Line.

In fact,there were at least 3 Brisbane Lines: the military strategy( see A. Archives) Ward’s political version, and the lived experience of far North Queenslanders. There, the well- to- do bolted South, cane farmers were expected to destroy crops, the Army drilled holes in the wooden piles of bridges for explosive, dads dug slit trenches, kids were issued with a bit of hose tied to tape which you wore around your neck and bit on when bombs were dropped, and in early 1942 schools were closed.