Michael Piggott*

‘An out-of-shape homage to Ned Kelly’s murdered victims at Stringybark Creek’, Honest History, 25 January 2021

Michael Piggott reviews Doug Morrissey’s Ned Kelly: The Stringybark Creek Police Murders

With this book, Doug Morrissey and Connor Court Publishing end their Kelly trilogy. It started with a biography in 2015, followed three years later by a study of the geographical economic religious and social contexts of north-east Victoria in the 1840s to 1880s. Morrissey having immersed himself in the Kelly phenomenon since childhood and continued with honours (1977) and doctoral (1987) theses at La Trobe University, this third book is probably his final word on the subject.

In all three volumes, Morrissey’s extensive and critical use of primary sources has been intense, as has been his knowledge of contemporary newspapers and the secondary literature. And all complemented by familiarity with lingering community feeling and alertness to the powerful contribution of oral tradition to mythmaking. Drawing on these sources, Morrissey has sought to challenge the popular view of Kelly as the larrikin hero and symbol of rebellion who defended his family and the wider Irish immigrant community and who was driven to crime, including murder.

In all three volumes, Morrissey’s extensive and critical use of primary sources has been intense, as has been his knowledge of contemporary newspapers and the secondary literature. And all complemented by familiarity with lingering community feeling and alertness to the powerful contribution of oral tradition to mythmaking. Drawing on these sources, Morrissey has sought to challenge the popular view of Kelly as the larrikin hero and symbol of rebellion who defended his family and the wider Irish immigrant community and who was driven to crime, including murder.

The latest volume is both similar to its predecessors – the sources and prosecuting a view are again to the fore – but different, too. While the first volume was essentially a biography and the second social history, this third, despite its title, is only partly an account of the police murders and the events leading to them (Chapters 5-9). This clearly was the book’s primary aim, and it presents compelling argument and evidence that the police were indeed ambushed and murdered.

All the more disappointing then that, to me, the author’s pursuit of additional concerns, and other extraneous content (to be discussed below), pushed out of shape the book’s focus as a work of historical narrative. One distorting feature is the inclusion (Chapter 10, ‘Who speaks for the victims?’) of Victim Impact Statements from descendants of two of the three police murdered at Stringybark Creek on Saturday, 26 October 1878 – family representatives of the third murdered policeman could not be located – and from the grandson of Constable McIntyre, who escaped.

One of these descendants, Leo Kennedy, a great grandson of Sergeant Michael Kennedy, also wrote the book’s introduction, and in 2018 separately produced his own history, Black Snake: The Real Story of Ned Kelly. In Morrissey’s book there is also Appendix II, ‘Stringybark Creek Police Memorial site’, including similar statements from the three families’ descendants. Since 2018, these have been presented on commemorative plinths at the memorial.

The second more serious concern is the inclusion of the transcript of a family memoir written by Constable Thomas McIntyre, the ‘fourth’ policeman and only eyewitness to one of the Stringybark Creek murders. It is undeniably a central document on the murders and Kelly’s story in general, especially considering McIntyre wrote his first report within 24 hours of his escape and gave sworn evidence to Kelly’s committal and trial and the 1881 Royal Commission. The memoir came later, in 1900.

Morrissey quotes from the 1900 memoir repeatedly throughout his book and, though the memoir was written 22 years after the murders, sees it as a counter to Kelly’s 1879 Jerilderie Letter which, among many other assertions and justifications, in effect argued the police brought their deaths on themselves. In his 2015 biography Morrissey reproduced and critiqued the Jerilderie Letter in an appendix without overwhelming that overall text. Here, the inclusion of McIntyre’s memoir in its entirety is truly puzzling, its 11 chapters taking up over half the book’s 400 pages (pp 173-377). In any case, the memoir was first published in shorthand in 1901, while a transcript has been available since 2007 online at the Victoria Police Museum website.

Unfortunately, there are other features of the book’s content and structure which detract from rather than complement the core content. There are coloured maps, a chronology and five appendices (some of minimal relevance at best) but, unlike the first two volumes, no index. Quotes from sources appear on practically every page but carry minimal identification; there are no footnotes or endnotes. There are also dozens of references to pro-Kelly authors but they are rarely named.

In contrast, there are over 500 footnotes supporting the author’s editing of the McIntyre memoir. There are also inclusions such as poetry from contemporary newspapers and illustrations (e.g., a poster for Ben Squared Films’ Stringybark) scattered throughout, inclusions which to me had only marginal relevance to the book’s argument. One, headed ‘Ned’s account of the Stringybark Creek murders’ (pp xx-xxi) is further described by the author as ‘Abridged and rephrased from the Cameron (1878) and Jerilderie (1879) letters’. As such, this concocted text is not helpful, especially as one of the central issues about the letters (and McIntyre’s memoir, incidentally and still debated 140 years later) is the degree of warning the Kelly gang gave the police before firing.

Film poster for Stringybark (aguidetoAustralianbushranging.com)

Film poster for Stringybark (aguidetoAustralianbushranging.com)

In summary, this final volume is the weakest of Morrissey’s three. The publisher must share a responsibility for this. Apart from Connor Court’s usual poor proofreading (increasingly these days done by algorithms) it indulged the author, who has loaded the book up with too much detail of too little relevance. Besides the McIntyre memoir, he has given a run to pet hobby horses about Kelly films and channelled the police descendants’ understandable hurt into futile calls for Sergeant Kennedy’s watch to replace the ploughshare armour as a national symbol.

For those not prepared to buy or borrow the Morrissey books or devote the time to reading them, there is a more succinct and just as powerful statement of Morrissey’s views under the heading, ‘Time to bury the Kelly myth’, freely available on the Quadrant website. Meanwhile, there are some more general points to be made.

***

Beyond The Stringybark Creek Police Murders itself is the ever-present, ever-changing Kelly phenomenon – an older, smaller version of Anzackery. Reluctantly refamiliarising myself for this review with a selection of blogs, websites and social media, I was struck again by the nature of this vast rabbit warren, teeming with passions, loyalties and obsessions, some of them shocking in crassness and viciousness. Publishers continue to prove the Kelly name and iron mask image sell, and, as Doug Morrissey himself has shown in ‘The heritage marketing of Ned Kelly’, libraries, museums and tourism operators continue to rely on the Kelly trope rather than find an original creative angle.

The broader community and family resentments behind the Kelly gang’s actions have flourished and festered too. In 1960, the graves of the murdered police at Mansfield were vandalised, in the 1970s the Stringybark Creek murder site was commercialised, and the police names obliterated, and in the early 2000s a memorial stone was repeatedly defaced. A rededication ceremony of the graves in 2013 resulted in Internet trolling of the police family descendants.

For the Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce, ‘All history is contemporary history’, while American novelist EL Doctorow wrote, ‘history is the present’. Recently, Anna Goldsworthy insightfully commented that

perhaps the real vanity lies in imagining we can meet the past on its own terms … All culture is subject to the editorialising of the present – to our amendments and annotations – regardless of whether we know we are doing it. We pass it forward, covered in our fingerprints, even if we think we are wearing white gloves. Even if we imagine, as citizens of the present, that our gaze is the truly transparent one.

It is not a stretch to think of Donald Trump’s presidential term as a relevant parallel, given his approach to truth and facts and, on the other hand, that for many decades the words ‘true’ or ‘real’ have been obligatory labels for Kelly films, novels and biographies. But who then are our equivalents to American immunological expert, Dr Anthony Fauci, the epitome of professionalism, confronted with ignorance and bluster?

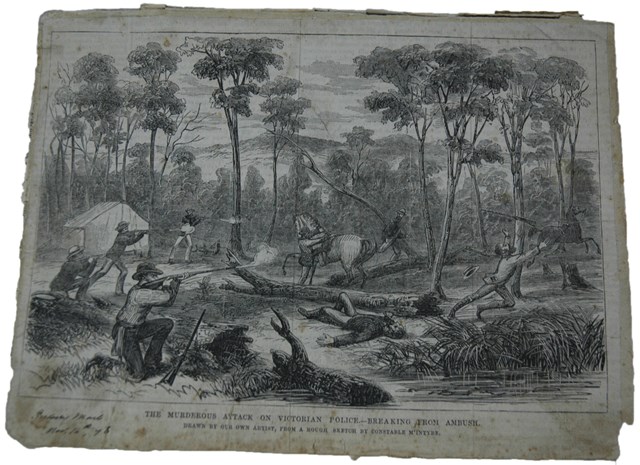

‘The murderous attack on Victorian Police – breaking from ambush’: Sydney Mail, 16 November 1878 (Culture Victoria)

‘The murderous attack on Victorian Police – breaking from ambush’: Sydney Mail, 16 November 1878 (Culture Victoria)

Occasionally when reading Morrissey’s book, I thought his expertise as a highly qualified historian had faltered. At times, his judgement about reliability of historical witnesses became too polarised: the testimony of Kelly and Kelly supporters is self-serving while the police tell the truth. At times, too, Morrissey’s faith in primary sources is too simplistic, as he ties himself in contradictory knots, like in his discussion of Sergeant Kennedy’s bloodstained notebook with its missing pages. His speculation to fill gaps in the sources is too often partisan.

Sometimes, too, restraint – like that displayed by Dr Fauci in press conferences – is missing in Morrissey’s work. He describes a recent film which presents Kelly as ‘a beardless, queer crossdresser’ as a ‘postmodern cauldron of movie madness’ (p 398) and criticises today’s justice system towards murderers as too lenient (pp xiv and 171). Such angry vents are as unnecessary as was his comparison in 2017 of the Kelly gang with ‘Melbourne’s gangs of African teenagers’.

For me, the recent ‘Palace Letters’ debate resonated, too. We’ve had two books, one by journalists Paul Kelly and Troy Bramston, the other by Jenny Hocking, drawing strongly contrasting conclusions from basically the same documents and shared republicanism. Yet, the authors’ opinions about historical accountability differed sharply, Kelly and Bramston seeing the events behind the Palace Letters as over and now passing into history, Hocking drawing urgent lessons of independence, accountability, and transparency. Reviewing their accounts in the Australian Book Review very recently, Jon Piccini concluded that they ‘cannot rely on history itself to change well-established patterns of thought, prejudice, and privilege. Only the hard slog of politics can do that.’

It was the politics of Covid-19 lockdowns last year which conjured Ned Kelly yet again, as if to illustrate Manning Clark’s prophetic words, ‘Ned was not to vanish like the dream that dies at the opening of the day’ (A History of Australia, Volume IV, p 336). In September 2020, Victorian Premier Dan Andrews’ insistence on a hard lock-down was likened by Barnaby Joyce to Ned Kelly, and Doug Morrissey agreed. ‘The comparison is apt’, he wrote, later comparing Andrews’ daily press conferences to ‘Ned in his egomaniacal Jerilderie Letter’!

Ah, well, ‘established patterns of thought, prejudice, and privilege’. Such is the life of an historian.

* Michael Piggott AM is a semi-retired archivist with many years’ experience and has been Chair of the (ACT) Territory Records Advisory Council. He has a chapter in The Honest History Book. In 2020, he contributed chapters to Community Archives, Community Spaces: Heritage, Memory and Identity (Bastian & Flinn, ed., Facet, 2020) and “All Shook Up”: The Archival Legacy of Terry Cook (SAA & ACA) and wrote the Australian chapter for a forthcoming text on archival silences. He has written many book reviews and other pieces for Honest History (use our Search engine), most recently reviews of I Wonder: The Life and Work of Ken Inglis, edited by Peter Browne and Seumas Spark, and a Parliament House exhibition on Edmund Barton.

Victoria Police Chief Commissioner Graham Ashton and Leo Kennedy, great-grandson of Sergeant Michael Kennedy, Stringybark Creek Memorial redevelopment ceremony, December 2018 (ABC/Chloe Strahan)

‘Ned’s “… egomaniacal Jerilderie Letter’!”

This is one of Australia’s greatest contributions to satire, Swift! Mark Twain! Ned Kelly!

“What would people say if they saw a strapping big lump of an Irishman shepparding sheep for fifteen bob a week or tailing turkeys in Tallarook ranges for a smile from Julia or even begging his tucker.”

“Brooker Smith superintendent of police he knows as much about commanding police

as Captain Standing does about mustering mosquitoes …”

etc, etc.

Well done by Mr Piggott.