Michael Piggott*

‘Wondering about the long and well-lived life of historian, Ken Inglis’, Honest History, 14 April 2020

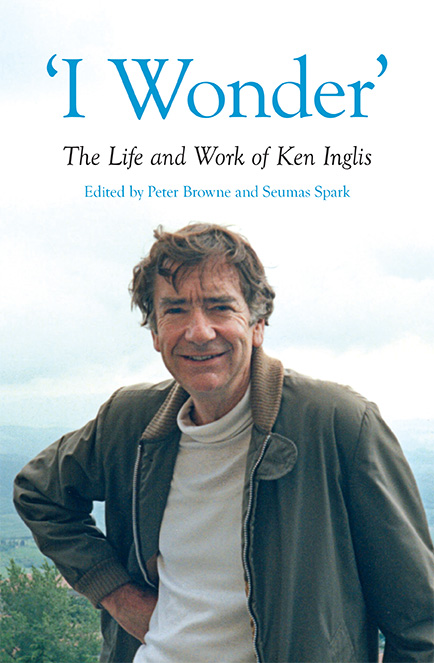

Michael Piggott reviews ‘I Wonder’: The Life and Work of Ken Inglis, edited by Peter Browne and Seumas Spark

In ‘Looking at memory’, Chapter 20 of ‘I Wonder’, Professor Annette Becker of the University of Paris-Nanterre acknowledges Ken Inglis’s seminal international contribution to the study of memorials and commemoration. There, Becker chooses to honour and emulate Inglis’s ‘War memorials: Ten questions for historians’ (1992) by posing her own. Becker’s is one of the book’s best tributes and prompts us to adopt a similar structure. While what follows occasionally implies reservations, this is overall a most impressive book testifying to an eminent writer and thinker and generous human being.

1. A Festschrift?

‘Festschrift’ to some is a pretentious anachronism. Most definitions say it is a volume of essays presented by colleagues, friends and former pupils to a distinguished teacher or scholar. In the strict meaning, the publication marked a birthday, but gradually the pretext came to include the end of a career or long term of journal editorship – in one case, even presidency of an Oxford college. Sometimes the volume, usually a well-designed hardback, followed a death and served to honour and celebrate a lifetime’s output. Typically, the chapters reflected on or responded to the scholar’s research; occasionally, they included something from the subject him or herself.

‘Festschrift’ to some is a pretentious anachronism. Most definitions say it is a volume of essays presented by colleagues, friends and former pupils to a distinguished teacher or scholar. In the strict meaning, the publication marked a birthday, but gradually the pretext came to include the end of a career or long term of journal editorship – in one case, even presidency of an Oxford college. Sometimes the volume, usually a well-designed hardback, followed a death and served to honour and celebrate a lifetime’s output. Typically, the chapters reflected on or responded to the scholar’s research; occasionally, they included something from the subject him or herself.

Even this outline has had dozens of variations. The editors of Body and Mind (ed. Pat Jalland, Melbourne University Press, 2009) saluted FB Smith, with no specific trigger about a decade after his retirement. Prisca Munimenta: Studies in Archival & Administrative History presented to Dr. A.E.J. Hollaender (ed. Felicity Ranger, University of London Press, 1973) marked its subject’s double retirement that year as Keeper of Manuscripts at the Guildhall Library and foundation editor of the Journal of the Society of Archivists, and did so by recycling twenty-two of the Journal’s articles. Another variant is Tasmanian Insights, subtitled ‘Essays in Honour of Geoffrey Thomas Stilwell’. Edited by Gillian Winter and published by the State Library of Tasmania in 1992, it neither celebrated Stilwell’s life (d. 2000) nor long career, including Curator of the Allport Library (ret. 1995).

History on the Edge (University of Melbourne History Department, 1997) brings us closer to our specific focus. Of its essays, editor Mark Baker noted they ‘began as a Festschrift to the life of John Foster but sadly ended as a Yizkorbuch – a Memorial Book’. Emotion readily influences these publications’ shape, often, as in the case of Tom Stannage: History from the Other Side (ed. Deborah Gare and Jenny Gregory, Studies in Western Australian History, 2015), explicitly initiating them. Or indeed delaying them, as I have known from involvement with a volume honouring a renowned Canadian archival colleague.

2. What, then, is this book?

Even against this background, Browne and Spark’s selection of writing about Ken Inglis is quite a mix – in tone, content and timing. Not original research presented to him on a birthday, only in part a ‘witness seminar’ of group recollections. And appraisals of course, delivered in his presence then, after his death, revised for publication with other commissioned writing. I’m not sure what I’d call the collection considered as a whole.

Most essays in the book began as papers to ‘Ken Inglis in History: A Laconic Colloquium’, held in late November 2016 at Monash University, Melbourne, with Inglis himself present. Other essays were commissioned afresh or reprinted after first appearing in History Australia. Two are reproduced exactly as read at the colloquium. These facts alone justify the overused label ‘uneven’. A few chapters are thin, sparsely referenced, ‘Ken and me’ recollections of limited interest and leaving the reader feeling excluded. One chapter was not even about him. The best two-thirds of the offerings, though, provide carefully researched biographical insight or authoritative intellectual context to and appraisal of Inglis’s thinking and research, backed by thirty to fifty notes and access to his papers and oral history interviews.

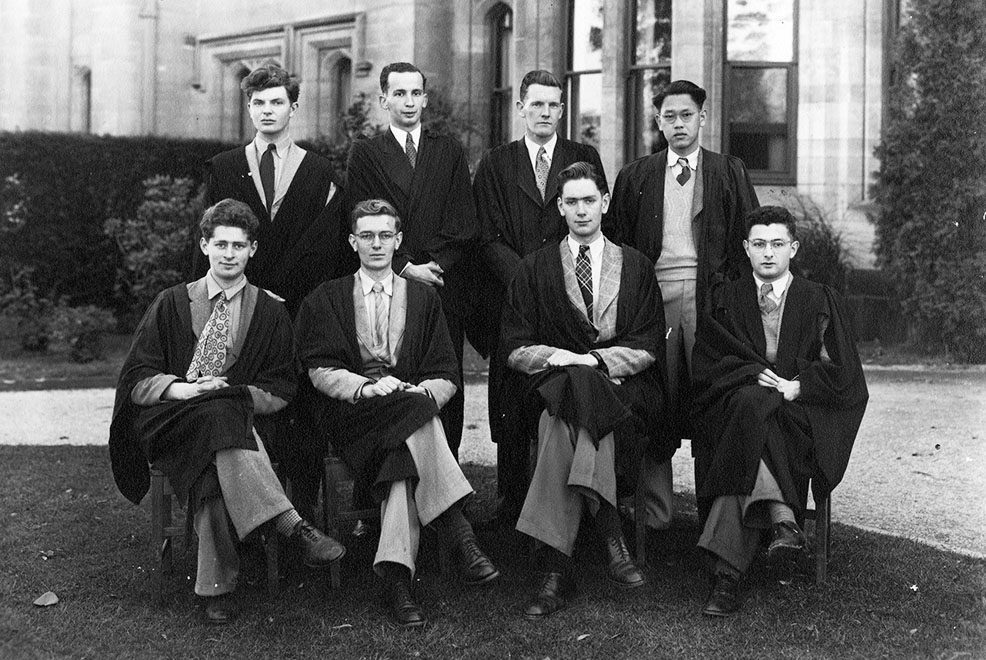

Ken Inglis, second from right in front row, at Queen’s College, University of Melbourne, early 1950s (Inside Story/Ken Inglis)

Ken Inglis, second from right in front row, at Queen’s College, University of Melbourne, early 1950s (Inside Story/Ken Inglis)

3. In a sentence, who and what was Ken Inglis?

There is always a need to sum up a life in a headline, press release or ‘who was he?’ answer. Russel Ward once rated Inglis ‘the greatest historian in the country’; even forty years ago, Rob Pascoe called him ‘Australia’s leading sociological historian’. The Sydney Morning Herald sub-editors headed Tony Stephens’ obituary of 16 January 2018, ‘Anzac historian, foremost a storyteller’. The man himself was quoted as having self-summarised, ‘I am first and foremost a storyteller’. Through such telling, we learn that Inglis thought all good historians try to change the way their readers see things.

Michael McKernan’s Canberra Times review (21 March 2020) went one better with the title ‘A great and gracious Australian,’ seeing Inglis as ‘one of the greatest Australians to have given his all to this country’. McKernan savoured positive memories – like so many of the book’s contributors – but still described the book (I think correctly) as a work of love and piety, if ‘occasionally fawning’. Morag Fraser said in the Sydney Morning Herald, it’s not a hagiography; ‘Ken would not have tolerated one’. Not if he’d been alive and genuinely had a veto, anyway.

Perhaps a volume based on a celebratory colloquium organised by close colleagues and friends, with the man himself present, does not even need to sum up the man’s life and work? The editors’ Introduction just gives the book’s origins and there is no final summing-up chapter. We are left with the dustjacket flap: ‘one of Australia’s most creative, wide-ranging and admired historians’ and a ‘much-loved historian and observer of Australian life’. That’ll do.

4. Is ‘I Wonder’ a biography?

A striking aspect of the book is its structure, specifically the question of its human boundaries. Granted, in a sense the entire volume is biographical, but how much really does it address the ‘life’ of its subtitle, aside from Scates and Frances’ chapter on Inglis’s high school years? Scattered throughout there are some genuinely revealing nuggets of personal detail by people who knew Inglis or consulted papers and interviews. There is nothing by any of his children, however, unlike, for example, the volume honouring another historian, Hank Nelson.

We do have a piece (chapter 7) by Shirley Lindenbaum – Inglis’s sister – though the family connection is provided by the editors, not her. Presumably, focussing just on Inglis’s anthropological sensitivities, she thought it irrelevant to mention the family link. There is also a fine chapter about Ken’s second wife, Amirah Inglis, her family and her life as activist and scholar, yet curiously there is almost nothing about his first wife Judy (d. 1962), essentially just mentions in the chapter on the Stuart case and passing nods by her sister-in-law.

We do have a piece (chapter 7) by Shirley Lindenbaum – Inglis’s sister – though the family connection is provided by the editors, not her. Presumably, focussing just on Inglis’s anthropological sensitivities, she thought it irrelevant to mention the family link. There is also a fine chapter about Ken’s second wife, Amirah Inglis, her family and her life as activist and scholar, yet curiously there is almost nothing about his first wife Judy (d. 1962), essentially just mentions in the chapter on the Stuart case and passing nods by her sister-in-law.

Judy Inglis was a wife and mother like Amirah, and just as significant in her own right (as an ‘activist anthropologist’) as well as influential on Inglis’s developing thinking, through her Oxford studies and connections (including Evans-Pritchard). She is better acknowledged by Frances and Scates’ sensitive Australian Historical Studies obituary of Ken than in this book, and better remembered at the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

5. What if?

What would Ken Inglis, a student of the rituals of commemoration and memory all his life, have made of such memorial volumes and the pilgrimages to reunion events which launch them? We can so readily hear him ask who got invited, who contributed, how were the encomiums worded, and what can we learn from Durkheim and Geertz? (After all, several of the book’s contributors, including Shirley Lindenbaum, Marian Quartly and Graeme Davison, noted his feel for anthropological and sociological concepts.)

Inglis had contributed to tribute volumes (e.g. about John Mulvaney and Hank Nelson) and he’d organised and performed at others’ farewells. As Diane Langmore recounts (p. 196), he had to suffer his own two-day seminar and dinner at the ANU in 1994. ‘Deeply reluctant’ by nature ‘to put himself in the spotlight’ (Marian Quartly, p. 287), in 2016, aged 87, he was trapped in his own case study. Weary to the bone, still being importuned for journal articles and desperate to finish his Dunera research, he was clearly bullied into submitting to another seminar (Introduction, p. xv).

Just over a year after the 2016 event, Inglis was dead. Drawing on Martin Crotty’s revealing chapter, ‘The book that never was’, about the 1965 Gallipoli pilgrimage Inglis accompanied and selectively reported on, we can guess what he might have noticed but, Bean-like, politely chose not to mention. He’d have recognised the alpha reminiscers – mostly men – swapping stories of japes and who said whats, and the organisers with their agendas and justifications. Ironically, the nascent Anzackery of 1965 had become by 2016 a colloquium to a hero veteran – an event which its hosts ingenuously called a ‘Kenfest’.

6. Did Ken Inglis ever sleep?

My overwhelming impression from reading ‘I Wonder’ was Inglis’s productivity. As many have commented and the editors’ bibliography attests, his output was prodigious and sustained over many decades, working into the last month of his life in late 2017. Atypical for someone who was an academic historian his entire adult life, his writing ranged over journalism and commentary, popular monographs and scholarly journal articles, book chapters and conference papers. And, as many of the book’s appraisals by renowned Australian and international scholars explain, his mastery of so many diverse questions, time periods and themes was so often prescient of their emerging significance. Especially Anzac.

My overwhelming impression from reading ‘I Wonder’ was Inglis’s productivity. As many have commented and the editors’ bibliography attests, his output was prodigious and sustained over many decades, working into the last month of his life in late 2017. Atypical for someone who was an academic historian his entire adult life, his writing ranged over journalism and commentary, popular monographs and scholarly journal articles, book chapters and conference papers. And, as many of the book’s appraisals by renowned Australian and international scholars explain, his mastery of so many diverse questions, time periods and themes was so often prescient of their emerging significance. Especially Anzac.

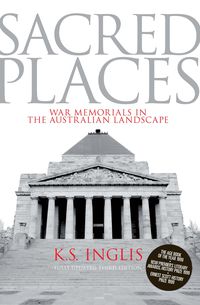

Further underlining this inexhaustive capacity, some publications were as much decade-long team projects as they were straightforward monographs, as we learn from the chapters by Peter Stanley on the three editions of Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, Marian Quartly on the eleven volume bicentennial Australians: A Historical Library and Glyn Davis on the ABC histories, This is the ABC and Whose ABC? He was chair of the Australian Dictionary of Biography editorial board for nearly two decades (1977-96).

We should remind ourselves, too, that this output happened alongside numerous academic duties – supervising doctoral students, commenting on other authors’ drafts, teaching, contributing to seminars, travel, reading, correspondence, undertaking departmental and related university responsibilities, and not to forget his term as a Vice-Chancellor. Nor did he neglect the niceties natural to a community of scholars, including making newcomers welcome. As his colleagues testified, all this happened with grace, patience and thoughtfulness.

Clearly, the scholar-journalist-writer could draft quickly and ‘edit without looking at a page’ (p. 345); the analytical historian knew not to agonise waiting for certainty, knew that asking the right question was often enough for the moment. Not everyone is so blessed, or learns how to do this, as Inglis did in part surely because of his journalism. In 2016, writing about the late David Sissons, the expert on Australia-Japan history, Arthur Stockwin called him ‘a mind of great subtlety and historical understanding’ and yet ‘meticulous in everything he did, to the point where his innate perfectionism inhibited him from publishing much of his research because he was not satisfied that he had fully covered very aspect of the subject under review’. That was not Inglis.

7. Warts and all?

With tribute collections, the choice of contributors shapes the resultant image. Of course, that’s an obvious point, yet an important one, because by their nature such volumes are unique. Serious reviews of ‘I Wonder’ will add a little, and we now have access to an edited version of Tom Griffiths’ launch speech. It is a gem and should be read as a companion to this book and indeed to Griffiths’ The Art of Time Travel: Historians and Their Craft (Black Inc, 2016). (Reviewed for Honest History by Diane Bell.)

Discussing critics’ response to Inglis’s third monograph, The Australian Colonists (MUP, 1974), Frank Bongiorno quipped, ‘Academic politics never takes a sabbatical’ (p. 229). Why certain chapter authors in this collection were chosen over others is not for us to know. We will never learn – however astutely we think we can guess – what Carolyn Holbrook, Jill Matthews, Marilyn Lake, John Moses or Humphrey McQueen might have said in front of Inglis in November 2016 or indeed in less compromised circumstances.

So far, too, the experiences from around the kitchen table are missing. Is there yet scope for some equivalent of Russel’s daughter, Biff Ward’s In My Mother’s Hands (Allen & Unwin, 2014)? Even, down the track, may there be a fully developed Inglis biography of the scale of the one Mark McKenna produced on Manning Clark (An Eye for Eternity, MUP, 2011)? Enough papers have been preserved to sustain one.

So far, too, the experiences from around the kitchen table are missing. Is there yet scope for some equivalent of Russel’s daughter, Biff Ward’s In My Mother’s Hands (Allen & Unwin, 2014)? Even, down the track, may there be a fully developed Inglis biography of the scale of the one Mark McKenna produced on Manning Clark (An Eye for Eternity, MUP, 2011)? Enough papers have been preserved to sustain one.

Finally, it is a pity that, for whatever reason, there is no authentic Papua New Guinean voice, given Inglis’ time there (1967-75). The editors’ use of a portrait by Nigerian Oseha Ajokpaezi, an arts lecturer during Inglis’ time as Vice-Chancellor at the University of PNG, serves to point up the absence. So did the apology at the colloquium from Sir Rabbie Namaliu, in the late 1960s and early ‘70s a student of Ken’s, then his friend and academic colleague.

8. Who were the Sherpas?

We glean from the book the sense that Inglis’s researching and writing style was largely solitary. He did much of his own typing and filing of cards, newspaper cuttings and photocopied articles, although equally he benefitted from research assistance and, for Sacred Places, from volunteers from around Australia. His formal acknowledgements are generous and comprehensive: in The Australian Colonists he thanked no less than eight women for typing his manuscript, definitely justifying notice from the #ThanksForTyping movement, acknowledging the women behind male writers!

As research assistant, Jan Brazier was in a category of her own, helping with The Rehearsal: Australians at War in the Sudan 1885 and This is the ABC and, in the case of Sacred Places and Nation: The Life of an Independent Journal of Opinion 1958-1972, also being formally named on their title pages. Peter Stanley quotes Inglis describing Brazier as ‘a good rummager’ (p. 310) and in the Introduction (p. 3) of the first ABC book Inglis called her work ‘indispensably imaginative, energetic and meticulous’.

For his entire formal working life Inglis was part of a community of scholars who were supported by research and clerical assistants, librarians and archivists. It was a pre-smartphone, pre-digitisation era where original research included, as Janet McCalman put it ‘the painstaking pre-Trove and pre-Argus Index reading of newspapers’ (p. 62). She and Joy Damousi (p. 301) were almost the only contributors to notice the research modes that sat just beyond sight of the book’s biographical outlines. A different kind of volume, perhaps with a chapter by a feminist scholar such as Maryanne Dever, might have examined some of the wider contexts of academic labour, ‘once an elite practice available principally to the privileged few with time, money and credentials’.

9. Was the bibliography justified?

The editors’ 18-page bibliography is a most impressive achievement and an important inclusion. It was crucial to the volume’s purpose because, being chronological, it so clearly illustrates its subject’s lifelong productivity. At a glance, one also sees just how many of Inglis’s works were reprinted, some of them three or four times, and not forgetting the anthologies edited by John Lack (Anzac Remembered: Selected Writings of KS Inglis, University of Melbourne History Department, 1998) and Craig Wilcox (Observing Australia 1959-1999, MUP 1999).

Compiling the bibliography must have been a challenge, not least given Inglis’s journalism and publications unattributed or using a pseudonym. The editors concede they believe their effort is only 85-90 per cent complete, something I was able to confirm without a lot of effort. Note, too, this list comprises just written works and does not cover radio broadcasts and speeches. Perfection would demand we add the oral history interviews Inglis conducted (e.g. of Nation‘s Tom Fitzgerald) and his own extensive collections of personal papers at the National Library.

Compiling the bibliography must have been a challenge, not least given Inglis’s journalism and publications unattributed or using a pseudonym. The editors concede they believe their effort is only 85-90 per cent complete, something I was able to confirm without a lot of effort. Note, too, this list comprises just written works and does not cover radio broadcasts and speeches. Perfection would demand we add the oral history interviews Inglis conducted (e.g. of Nation‘s Tom Fitzgerald) and his own extensive collections of personal papers at the National Library.

10. Why just one photo?

Bouquets first. That Monash University chose to publish ‘I Wonder’ is to its enormous credit, as is its decision to keep the price within reason. The book deserves to at least break even, and one hopes the publisher’s Dunera volumes also enjoy brisk sales. The copy editing is high quality, and the physical product, a hardback with an inspired cover design and title, is similarly praiseworthy. Bravo, too, to the University of Melbourne for a grant which ‘aided greatly’ (Introduction, p. xvii) the publication. As noted, the editors included an extensive bibliography and, bless them, there is an index.

Puzzling then that, aside from the cover photo and the small Oseha Ajokpaezi portrait, there are no illustrations, and this is the book’s one real flaw. Plenty illustrations exist which seem to capture the essence of the man. A number were used as backdrops during the November 2016 colloquium, reminding us of another strange absence: the live video record of the colloquium presentations is available via Monash Arts yet not mentioned in the book itself. Anyway, check out the Kenfest, but buy the book too.

* Michael Piggott AM is a semi-retired archivist with many years’ experience, and is currently Chair of the (ACT) Territory Records Advisory Council. He has a chapter in The Honest History Book. His latest work is a chapter in Community Archives, Community Spaces: Heritage, Memory and Identity (Bastian & Flinn, ed., Facet, 2020). He has written many book reviews and other pieces for Honest History; use our Search engine.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.