‘Subversive stories of an old war’, Honest History, 1 December 2015

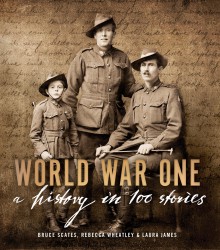

David Stephens reviews World War One: A History in 100 Stories, by Bruce Scates, Rebecca Wheatley and Laura James. Another review by Jim Windeyer.

__________________________________

This book is sentimental and sad but at the same time subversive. Here and there the prose is as maudlin as Australian War Memorial Director, Brendan Nelson, at full throttle; this reviewer cringed more than once. And cried. Then you realise that what you are reading is not emotion laid on thick for its own sake or to help readers ‘connect’ with dead men and women but rather emotion wielded cleverly to serve a number of worthy purposes.

The book is thick (384 pages), handsomely produced and illustrated (the Kindle version does it less than justice) and expensive (it looks like a coffee table book but it should be read more widely than other such volumes). It tells the stories of more than 100 people – some stories deal with siblings or families – who were affected by the Great War. There are stories of soldiers, of course, both during the war and after it, but also of nurses, voluntary workers near the front line and on the home front, anti-conscription campaigners and patriotic spruikers, searchers for bodies, stewards of war graves, malingerers and conmen, brave men and cowards, but most of all families, mothers and fathers, sons, daughters and siblings, waiting and grieving.

The book is thick (384 pages), handsomely produced and illustrated (the Kindle version does it less than justice) and expensive (it looks like a coffee table book but it should be read more widely than other such volumes). It tells the stories of more than 100 people – some stories deal with siblings or families – who were affected by the Great War. There are stories of soldiers, of course, both during the war and after it, but also of nurses, voluntary workers near the front line and on the home front, anti-conscription campaigners and patriotic spruikers, searchers for bodies, stewards of war graves, malingerers and conmen, brave men and cowards, but most of all families, mothers and fathers, sons, daughters and siblings, waiting and grieving.

There is in the book hardly any derring-do and heroic action in the face of the enemy. Instead, we get brothels, bureaucratic boorishness, conscientious objectors, desperation, domestic violence, evisceration, facial wounds, fear and loathing, Field Punishment No. 1 (including crucifixion), incompetence, injustice, maltreatment, mourning, pacifism, pain, poison gas, political unrest and repression, PTSD, sorrow, straitened circumstances, struggle, and venereal disease, all related in some way to the war. There is also Australian patriotism and Empire loyalty, bravery, compassion, comradeship, dedication, kindness, love, selflessness and stoicism.

In short, the book is about as wide-ranging a catalogue of war experience as any of us are likely to need or want. It is certainly far, far more comprehensive – and thus honest – than the received view of commemoration, the picture presented to visitors to the galleries of the War Memorial, or readers of the children’s war books peddled by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs or people attending many of the official commemoration fests during the Anzac centenary. That is why it is subversive.

This breadth of scope reflects the first and main objective of the book, which is, as Professor Scates said at the launch on Remembrance Day, to challenge and extend the way we remember the Great War. The current period of commemoration is a great time to mount such a challenge, particularly now as public enthusiasm for Anzackery (the supercharged form of commemoration) seems to be flagging. It would be a shame to sign off at the ‘commemoration fatigue’ stage when there is an opportunity to move on to something better.

That ‘something better’ would be an honest view of the whole-of-life, whole-of-family, life and living death experience of war, a view which is not easily softened by euphemisms like ‘supreme sacrifice’ and ‘died for our freedom’. These words are used to describe death in combat but they do not work well when applied to the experience of, say, Alfred Atkins, an elderly, lonely, misfit soldier who suicided after being bullied, or Rowley Lording, enlisted at 16, wounded, addicted to morphine during treatment, dead in a mental hospital three decades later, or Samuel Rolfe, gassed in France, who lived for much of four years after the war in a bath of boric acid to provide at least some relief before his lungs gave out and he drowned in his own fluids.

Bruce Scates, Laura James and Rebecca Wheatley (Monash University/Kara Rasmanis)

Bruce Scates, Laura James and Rebecca Wheatley (Monash University/Kara Rasmanis)

Secondly, 100 Stories aims to tell us about the people whom Professor Jay Winter described in his launch speech as the ‘little heroes’, the men and women who were at the disposal of men in positions of command, political and military. There was Tom Elliott, mown down at Fromelles, his body never found. Tom was not related to his commanding officer, the much more famous ‘Pompey’ Elliott, but Pompey wrote a kind letter to Tom’s mother, saying Tom could have become another Lord Kitchener or Lord Roberts. (Tom’s mother became deluded, alcoholic, and died of Spanish flu in 1919.) There were brothers Cyril and Rufus Rigney, Ngarrindjeri men from South Australia, killed at Messines and Passchendaele, consent for whose enlistment had been given by the Protector of Aborigines. There was Karanemar Pohatu, a Maori, whose pale skin helped him to enlist as ‘Robert Stone’ in the Australian forces but may have made him a better target when he was killed at Quinn’s Post.

[A]ll honour to those grand infantry privates who often got the rotten end of the stick, [wrote Reginald Biggs, veteran of the Western Front] rather than to the generals who sit back in comfort out of danger and hear about the victories which the humble soldiers have won for them.

Winter correctly saw the book as attempting to overcome the anonymity of mass death (‘61 000 dead in World War I’, ‘8709 dead at Gallipoli’, ‘2000 dead at Fromelles’), rescuing the small stories that have been eclipsed by manufactured national myths. The Australian War Memorial has tried its own modest bit of rescuing while not letting go of the myths. It now does a Last Post ceremony almost every evening, focusing on the stories of individual men and women. Those whose stories are told in this way are only those who appear on the Memorial’s Roll of Honour, that is, they are some of the 102 000 men and women who ‘died during or as a result of war service’; survivors, no matter how damaged they were or how badly they and their families were affected, do not feature. As to the form of the stories, the Memorial’s historians

determine the content of each story and ensure a consistent format … [C]ontent of the story remains at the sole discretion of the Memorial. Requests [from families] for specific information to be included in the story may not be possible.

Families proposing content following the style and philosophy of 100 Stories would not get very far.

To judge by the examples on the Memorial’s website, the standard script also has to include these words:

This is but one of the many stories of courage and sacrifice told here at the Australian War Memorial. We now remember [name of dead man or woman] and all of those Australians who have given their lives in the service of our nation.

There is no room there for questioning the received version of death in war; individual stories are expected to reinforce ‘the old lie’.[1]

Inaugural Last Post ceremony, Australian War Memorial, 2013, with VC winners and Director Nelson (Sydney Morning Herald/Rohan Thomson)

Inaugural Last Post ceremony, Australian War Memorial, 2013, with VC winners and Director Nelson (Sydney Morning Herald/Rohan Thomson)

This is definitely not a book about heroes dying for causes. Winter, who must have read at least some CEW Bean to come to his conclusion that the war historian is ‘unreadable’, implied that Bean’s patriotic purpose led him to inflate his characters (particularly the officers, whose accounts he mostly relied upon) to super-size. This point may be hard to grasp at our metropolitan shrines and cenotaphs or at the War Memorial in Canberra, where the frozen figures tend to be larger than life, Bean’s words are written bold on the wall and the website, and Bean (or a bowdlerised version of him, free of his occasional doubts and misgivings) still serves as a sort of holy, elongated mascot.

Thirdly, if the book is about little heroes, it also marks the arrival, again paraphrasing Winter, of a different breed of historians, younger, less traditionally academic, not ‘military historians’ but cultural and social historians dealing with war-related subjects, more inclined to work in collectives, keen to talk to relatives and amateur researchers and look at their mementoes, and less driven by the need to publish turgid papers in pay-wall protected journals mostly read by other academics. Professor Scates’ co-authors, Rebecca Wheatley and Laura James, are about the same age as the women who went to the Great War as nurses, like Evelyn Davies, Narelle Hobbes and Elsie Tranter, or provided support in other ways, like Ethel Campbell, South African friend of soldiers, and Ettie Rout, sexual health advocate. A century on, Wheatley and James essay new ways of benefiting the public, for example, in a free online course based on the book.

Next, 100 Stories tries to use new sources, most notably the repatriation files, the repositories of the medical and mental history of returned men and women. These files are starting to become available and they promise to rebalance our view of the Great War. Service files, properly read, show how small a proportion of an individual’s time in uniform is actually spent firing or under direct fire, as distinct from keeping one’s head down, trying to avoid dysentery, travelling to and from the front, or training well behind the lines. Taking the next step, repatriation files will remind us how relatively small a proportion of a long life is spent in uniform, compared with the decades afterwards, paying the price of ‘victory’.

The release of repatriation papers locked away for decades in doctors’ filing cabinets [say Scates et al] has made it possible to chart the postwar lives of those who volunteered in 1914. It reminds us of the aftermath of the Landing, extending our memory of Anzac well beyond that moment [Joseph] O’Grady [subject of one of the stories] and his comrades stumbled ashore.

Fifthly, the book confirms that history is messy. It would be easier to present and use if it could always be hung off big, hairy foundation myths (the city on a hill, the miraculous birth at Gallipoli) or squeezed into single channels susceptible to civics lessons (Western civilisation, egalitarianism). But – fortunately – it can’t be so simplified and distorted. Bruce Scates has often told of how the Commonwealth backed away from his project when he insisted on including the most scarifying of stories (specifically, the tale of the Wilkinsons, where shell-shocked, struggling soldier settler Frank destroyed himself and his family in the most horrible circumstances). The Introduction in 100 Stories has a senior public servant telling Scates that what the public wanted from the Anzac centenary was ‘a warm fuzzy feeling’. The Wilkinson horror story, Scates was informed, needed to be replaced by ‘a positive nation-building narrative’.

Private Joseph Bolton, died of wounds 1917, one of the stories in the book (AWM H06292)

Private Joseph Bolton, died of wounds 1917, one of the stories in the book (AWM H06292)

The Last Post stories at the War Memorial, described above, might not create warm fuzzy feelings but they certainly have a nation-building tone. That imperative to build a nation – a nation where war is seen as regrettable but necessary and sometimes even glorious – has been one of the drivers of Anzac centenary activities. This book takes us in a different – and powerful – direction. It would have benefited though from a concluding summary chapter to gently remind readers still caught up in the emotion that they were missing the point. Such a chapter could have extended the authors’ remarks in the Introduction that, as well as stories of ‘courage and sacrifice, fortitude and endurance, mateship and resolve’ we need to seek out the stories that have been marginalised. ‘We believe the Centenary is a time to gauge the cost of war for our entire community, and we believe that far from building a nation, the Great War tore us apart.’ Right on.

Jim Windeyer in his review of the book takes up sloppy proof-reading and literals and matters of grammar and approach, particularly the occasional use of ‘imagined history’. This reviewer was much less exercised than Windeyer about this last aspect – in the great majority of cases the amount of evidence provided is ample and the way it is used impeccable – but did find some annoying typos that should not have survived the first draft. The prose in some of the stories occasionally clunks but the greater goods which the book serves pull it round decisively. It should leave the reader profoundly affected – and deeply thoughtful – even if a little exasperated by the gloopy bits and the occasional carelessness. As for the points raised by Windeyer about whether Scates et al have written ‘honest history’, this reviewer can only refer readers to Honest History’s (the coalition’s) working definition of the term ‘honest history’ as ‘interpretation robustly supported by evidence’, which links nicely to EH Carr’s remark, ‘History means interpretation’.

Ultimately, the book has to be set against the received or official version of commemoration, with all of its baggage. Director Nelson of the Australian War Memorial, when quizzed early this year about arms manufacturers’ donations to the Memorial, made a revealing remark about its Afghanistan exhibition (funded by Boeing). ‘There is’, he said, ‘immense emotion revealed in that exhibition’. One could retort, ‘So what? Does the exhibition also ask any important questions or try to answer them?’ In spruiking the proposed Monash Interpretive Centre at Villers-Bretonneux, DVA repeatedly used the word ‘emotional’ (and other polysyllabic adjectives) to justify the project. Yet the real point, as Dr Nelson’s Council member Les Carlyon has said, is not to emote but to think.

When people are asked how they ‘feel’ during a commemorative occasion they often answer along the lines of ‘I’m feeling very emotional’. Now there are many emotions: Aristotle reckoned there were nine, Plutchik’s famous wheel has eight ‘basic emotions’, another list has more than twenty. What people mean by ‘emotional’ in the midst of commemoration is often no more than ‘teary’ or ‘all choked up’. Joan Beaumont in the documentary Lest We Forget What? asked Kate Aubusson to consider the emotion Kate was feeling as a World War I cemetery visitor a century on and then distinguish it from the emotion – grief – that the mother of a dead soldier would have felt soon after his death.

Sister Elsie Tranter, one of the stories in the book (AWM P09173.001)

Sister Elsie Tranter, one of the stories in the book (AWM P09173.001)

Other visitors to the grave of a great-great uncle whom they know only from faded photographs bizarrely gasp through tears about finding ‘closure’. It is difficult sometimes to tell whether the tears are for the dead or for the person doing the weeping, for ‘them’ or for ‘us’. Finally, do we feel sad about death in war partly because others are feeling sad? Can contagion and fashion drive commemoration fever just as they can drive other mass outpourings of emotion?

Regardless of what triggers an emotional response, it’s what we think and do next that counts. If 100 Stories does not have a wide readership and a wider impact it will be the fault of Australians, not of the book. It will show that this battle – the commemoration battle for the soul of a future Australia – is being won not by honest historians and their thoughtful readers but by the official and commercial promoters of khaki-tinged warm fuzzy feelings and by the Anzackers who seek to turn the tragic deaths of young Australians and the blighted lives of their families into good news stories and patriotic puffery.

______________________

[1] This is, of course, a reference to Wilfred Owen’s famous poem, Dulce et Decorum Est (1917-18), which ends, ‘The old lie; dulce et decorum est pro patria mori’ (‘It is sweet and right to die for your country’).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.