‘Is this “our story”? Another look at the Australian War Memorial’s refurbished World War I galleries’, Honest History, 3 March 2015

David Stephens takes a further look at the new galleries.

There are launches and launches. The Australian War Memorial did a ‘soft’ launch of its refurbished galleries way back in December, ostensibly to give the new work, costing $33.5 million, an opportunity to shake down before the ‘hard’ launch by the Governor-General on Sunday, 22 February.

As it turns out, the hard-launched galleries are not much different from the version we reviewed a month ago, following our close examination of them during December and January. We had another look the day after the honours were done by His Excellency, who was supported by the Director of the Memorial, Dr Nelson, Minister Ronaldson, author and Memorial Council member Les Carlyon, and the Hon. Maggie Barry MP from New Zealand, in the presence of former prime ministers Hawke and Howard and others.

Members of the New South Wales contingent to the Sudan listening to the reading of the Queen’s proclamation of thanks. The contingent arrived at Suakin on 29 March 1885, and left for Australia on 17 May 1885. (Australian War Memorial P08107.001)

Members of the New South Wales contingent to the Sudan listening to the reading of the Queen’s proclamation of thanks. The contingent arrived at Suakin on 29 March 1885, and left for Australia on 17 May 1885. (Australian War Memorial P08107.001)

We also checked with the Memorial media and exhibitions teams to make sure we had not missed anything. (The media team advised that surveys had shown overwhelming visitor satisfaction with the refurbished galleries; we asked for but were denied a copy of the findings. See Appendix to this post.) The sum total of changes is as follows: three big new-old guns outside; minor technical adjustments; a small content addition relating to widows. Separately, there has been an announcement about gargoyles.

From one point of view, the lack of difference between soft and hard launch is good: it suggests the Memorial felt it got the new galleries pretty much right the first time around. On the other hand, the deficiencies that Honest History identified in our earlier review are still present. There is still the clanging lack of context (before the war, after the war, other combatants), the sanitising of suffering, the lack of questioning, the implicit acceptance of war that James Rose drew attention to in our earlier piece, the risk of imprinting an attitude to war on impressionable children. There are still also the issues about captioning and ‘how-to’ information, although the lighting seems to be brighter.

The speeches delivered on 22 February reflect satisfaction with the outcome of the refurbishing work but, more importantly, a continuation of the way the Memorial has always done things. It’s conservative and backward-looking role was underlined again and again.

The War Memorial [the Governor-General said] is where we proudly present the military heritage that has inspired Australians for more than 100 years – and offers insight into some of what has gone into shaping and revealing who we are today.

This morning, we honour the fact that with the refurbishment of the First World War gallery, our national memory, conscience and unity has once again been strengthened by the Australian War Memorial.

Minister Ronaldson hoped that the new galleries would ‘inspire younger Australians to learn more about our history and give comfort to the memory of the fallen that indeed, We Will Remember them’. Director Nelson used moving quotes from CEW Bean and from an Australian soldier – words he has used in many previous speeches – and added further emotive remarks from the historian Neil Oliver about the love between soldiers. He commenced, however, with this sweeping claim about the place of the galleries.

In these First World War Galleries, our nation reveals itself in the men and women whose story it tells. It is who we were and who we are. Facing new and uncertain horizons, it is also a reminder of the truths by which we live, how we relate to one another as Australians and see our place in the world.

The Director also made another large claim: ‘Every nation has its story. This is ours.’ Story. Singular.

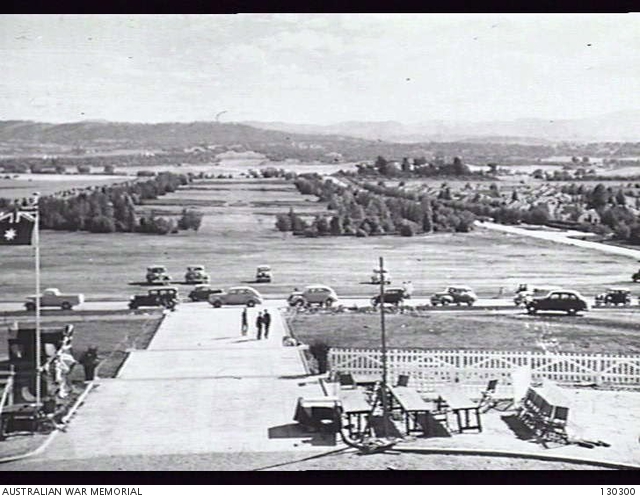

Australian War Memorial looking south, 11 November 1941, after inauguration ceremony (Australian War Memorial 130300/donation RW Conrow)

Australian War Memorial looking south, 11 November 1941, after inauguration ceremony (Australian War Memorial 130300/donation RW Conrow)

Soaring above the other speeches, though, was the keynote from Les Carlyon. He mostly eschewed hyperbole; he alone made a sustained attempt to confront context.

It is hard to under-estimate the place of that conflict in Australia’s story. It was perhaps not quite the nation-building event that some claim for it. Rather it was one of many. We had done some fine nation-building in the thirteen years after Federation.

We had created a unique society – the best of the British heritage but without the feudal hangovers. Ahead of the rest of the world we gave women the vote and the right to stand for Parliament. We introduced the secret ballot. We had a Labor Government in 1904, twenty years ahead of Britain. We said there had to be a minimum wage. We said there was something honourable about the self-made man.

We didn’t invent mateship, but we had developed a peculiar version of our own, based largely on the truism that it was just about impossible to survive in the bush without mates. The Great War interrupted those splendid beginnings, checked the creative tide. It became the worst trauma in Australian history, and still is.

While the other speeches touched lightly on the effects of war and made ritual disclaimers about not glorifying it none made the effort that Carlyon made to put the artefacts and the paintings and the dioramas into perspective. What a shame that so little of Carlyon’s breadth of vision seems to permeate the riding rules and rhetoric of the Memorial of whose Council he is a member.

The speeches were reinforced by the advertising, which referred to the Memorial holding ‘the greatest collection of objects from the First World War relating to the Australian experience’. The new galleries make ‘those objects available and their stories known to anybody who wants to come here’ (See Canberra Magazine, Canberra Times, Autumn 2015). When we asked the Memorial’s media people about any new features since the soft launch, we were asked whether we meant ‘any new objects’. The Memorial seems to expect that visitors will achieve an emotional connection with objects. (See also our review of Anzac Treasures.) Officials in the mediaeval church probably held similar expectations of pilgrims viewing pieces of the True Cross, though these officials were probably not as skilled and professional as the curators at the Memorial are.

At Senate Additional Estimates, Director Nelson referred to the Memorial’s Afghanistan exhibition, ‘which is extraordinarily powerful. There is immense emotion revealed in that exhibition.’ Yet even fostering an emotional connection to people, particularly dead soldiers (which is another strong theme at the Memorial) only takes us a small part of the way towards a proper appreciation of war. Emotion is understandable and inevitable in dealing with loss in war but it should not be at the expense of thought. In this connection, Carlyon’s concluding remarks are at least hopeful.

Peggy Noonan became famous as the speechwriter for President Reagan. The second-most famous speech she wrote for him was for an anniversary of the Normandy landings. When she was drafting the speech White House staffers kept coming up to her saying: “It’s got to be like the Gettysburg address – it’s got to make people weep.” She tired of people telling her this and eventually rounded on one of them and said: “The Gettysburg address doesn’t tell you to weep – it tells you to think.”

That, I believe, is the wonderful thing about these new galleries, their overarching virtue – they make you think.

Les Carlyon (Australian War Memorial)

Les Carlyon (Australian War Memorial)

The galleries would make us think much more if they broadened their focus, if they dealt not only with military exploits and the material relics they leave behind but also, more fully and honestly, with what happens beyond and after the battlefield – the human relics, if you like – and on why we were on the battlefield in the first place, whether it was worth it, and how we might avoid doing it again. Despite Carlyon’s optimism, the Memorial still avoids these questions.

It is clearly not the case that the Memorial’s current take on our war history is uncontested or uncontestable, even within its own circles, to judge by Carlyon’s speech. The growing public support for Honest History and for other dissenting voices suggests there are plenty of Australians who are uncomfortable with the Memorial’s approach. It would be great if the Memorial could wind back the hyperbole, the artefact polishing and the ancestor worship and engage in a real debate about the place of war in Australian society. Starting now. A century of doing basically the same rearward-looking commemorative things is surely long enough. Our children deserve a new approach. And if the Memorial reckons that its critics ‘simply don’t get it’ it should explain why it believes this is the case.

Appendix: An imagined conversation between a visitor and a child in front of a diorama

‘This is the Battle of Pozieres and this is a story about how the soldiers needed lots of socks.’

‘Wasn’t that where Great-Uncle Huey was wounded and gassed?’

‘Yes, it was. He was never the same afterwards. They reckon it was shell-shock but he’d never do anything about it. Auntie Mil used to say, “He’s got the horrors again”.’

‘Do they have any stories here about the horrors?’

‘Maybe it’s in another room. But let’s go to the Discovery Zone. That’s where they reckon you can dodge the sniper.’

‘It’s only pretend though, isn’t it, Mum?’

(Stories like Great-Uncle Huey’s are covered outside the Australian War Memorial by Monash University’s 100 Stories project. In 2009, the National Archives of Australia ran a touring exhibition, Shell-shocked: Australia after Armistice, which was reviewed here, along with a contemporary exhibition at the Memorial.)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.