John Shield*

‘The soldier settlers of Ubobo, south-west of Gladstone, have left only memories’, Honest History, 21 July 2019

On 13 August 1929 the Ubobo Branch of the Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia (RSSILA) held its annual general meeting in the Memorial Hall with ‘a good attendance’ of members. Roy (born Ronald John) Ramsay was re-elected president and William Binns likewise secretary. The Capricornian noted that the organisation’s spirit was ‘perhaps more in evidence in country districts, particularly in soldier settlement areas where returned men have pioneered together, inexperience and often physical disabilities crippling their activities’. I suspect not even that spirit could save the Ubobo soldier settlers.

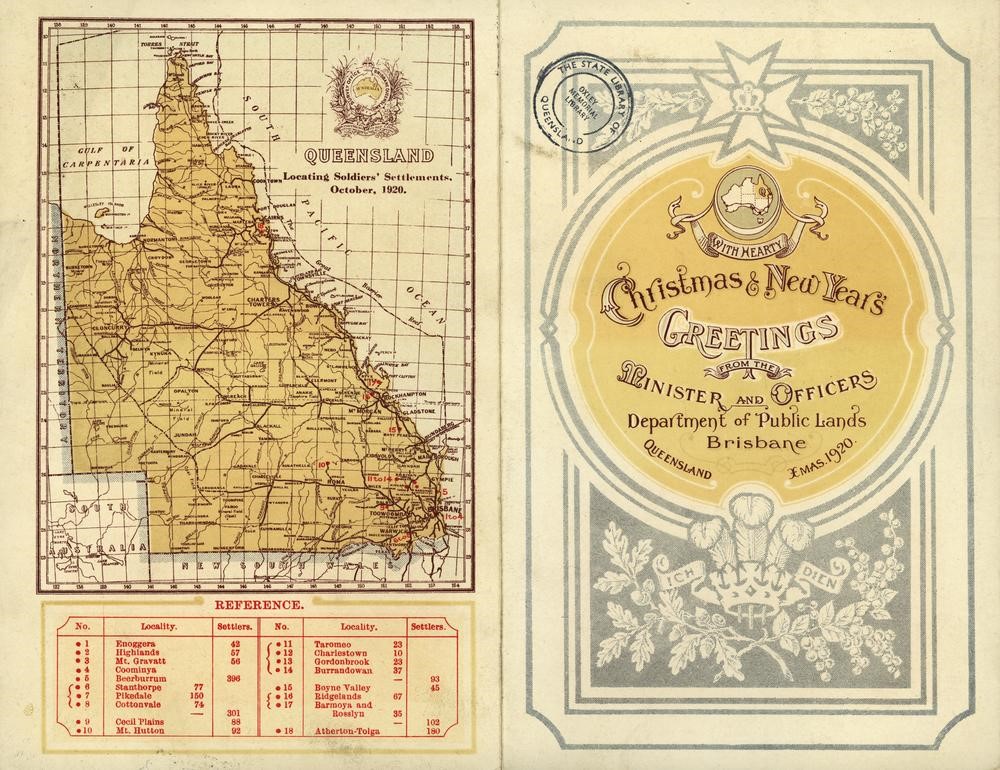

Marilyn Lake, and Bruce Scates and Melanie Oppenheimer have written the standard works on soldier settlement schemes in Australia, while Murray Johnson’s The Beerburrum Experiment is a fine study of the first soldier settlement in Queensland. In 1920, the Department of Lands issued a Christmas card with the locations of 20 soldier settlements, including number 16 in the Boyne Valley. The centre of the settlement was to be Ubobo.

Merry Christmas 1920 (Wikipedia).

Merry Christmas 1920 (Wikipedia).

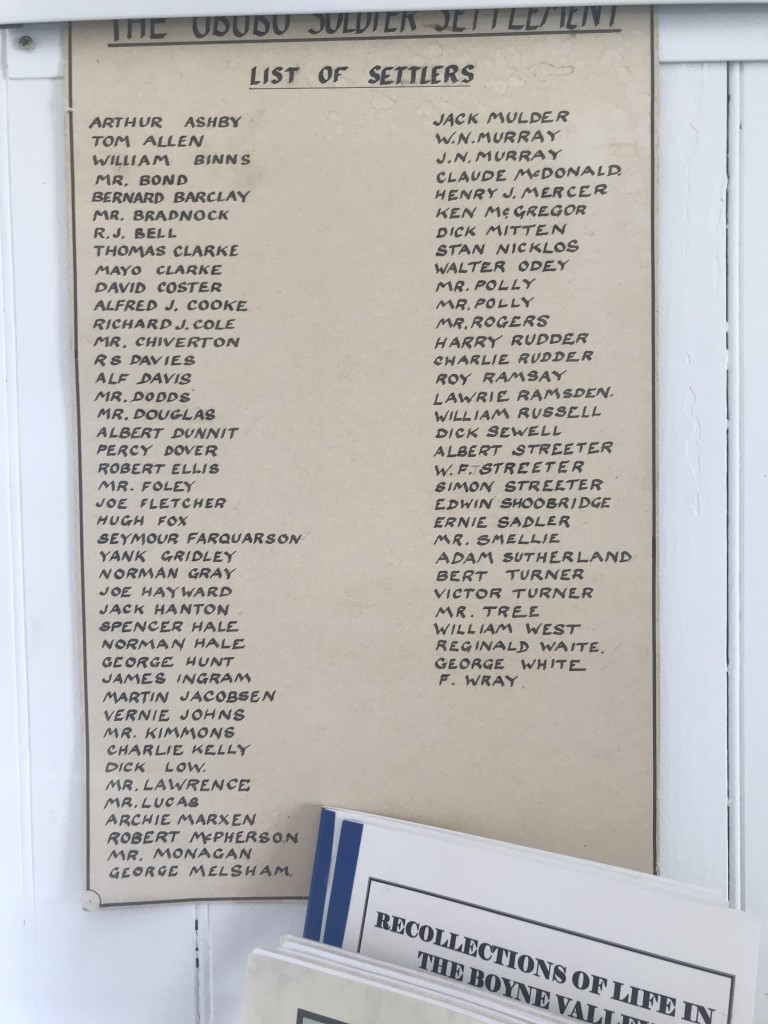

Ubobo is a tiny community about an hour’s drive south of Gladstone in Central Queensland. According to Wikipedia, ‘ubobo’ is an Aboriginal word meaning wild arrowroot. In 1920, it was quite literally a railway siding on the line running from the mine at Many Peaks to Gladstone. The Department of Lands resumed three pastoral leases, surveyed the approximately 15 000 acres and divided the area into 54 selections that were to be set aside for discharged servicemen. And while three does go into 54, the mathematical equation was to be the first of many elements that was to doom those who ended up at Ubobo.

In August 1923, the Brisbane Courier ran an article entitled ‘A happy corner’, noting that while ‘the affairs of so many soldier settlements are subjects for controversy’ the correspondent was pleased to report that in the Boyne Valley ‘prospects for a prosperous future are bright’. As you read the article, however, there are warning signs. The correspondent admits that in the dairy herds, averaging thirty cows in number, some of the cows were ‘not up to high milking standard’. The homes were ‘rather small’.

The most alarming problem, though, was that after three years the siding had not been improved, and even our optimistic correspondent admitted the ‘dilapidated … iron shed’ was insufficient to protect the cream cans from the sun and the weather. This deficiency was the subject of a number of letters to the newspaper from JN Murray, a landowner and Country Party candidate who, in arguing for a proper station noted, ‘[t]he practicing of economy by discriminating against returned soldiers should be strongly deprecated and … for the policy seems that … if there are 50 settlers let them have no public utilities whatever’.

Not only was there no movement on the railway, but the sudden influx of settlers placed demands on the local Calliope Shire, demands that it could not meet. The Bundaberg Mail’s report on the council meeting of June 1922 notes correspondence from Messrs E Sadler and AHE Polley complaining of the ‘exceptionally bad state’ of the roads near the siding and that they did not see the point of paying rates if the roads were not to be repaired.

Arthur Polley’s war had been a short one. He was shot in the head on 25 April 1915 at Gallipoli. He was taken to a hospital ship and was unconscious for four days. He awoke in Alexandria, his left arm paralysed and deaf and blind in his right ear and eye. After an operation which fixed the ear and eye he was shipped in October to London, where the president of his medical board declared him at three-quarters capacity to earn a full livelihood.

Polley returned to Australia in December 1915, spending three months in the 6th Australian General Hospital before being discharged on 14 March 1916 on a pension of three pounds, nine shillings a fortnight. So I guess a letter complaining about roads is fair enough, as he struggled to make something of his post-war life.

Edward Sadler’s service had been slightly more complicated. In the six months after the Gallipoli landings he had been thrice wounded and evacuated, shot in the cheek, shoulder and finally his right index finger. By February 1916, he was back in hospital with scabies, and then in April with, to quote his casualty form – active service, an ‘irritable heart’. He was back home by June.

Edward Sadler’s service had been slightly more complicated. In the six months after the Gallipoli landings he had been thrice wounded and evacuated, shot in the cheek, shoulder and finally his right index finger. By February 1916, he was back in hospital with scabies, and then in April with, to quote his casualty form – active service, an ‘irritable heart’. He was back home by June.

Applying for a war pension, Sadler was granted three pounds nine shillings per fortnight from September 1916. In October 1917, that was reduced to thirty-four shillings and then in March 1918 it was reduced again to twenty-three shillings.

Somehow, five years later the two men found themselves struggling to survive on their selections at Ubobo. After all they had been through no wonder they were irritated by the state of the roads, perhaps seeing them as a metaphor for their roads to recovery.

Neither Polley nor Sadler lasted in the Boyne Valley. But what of our president and secretary? Roy Ramsay had a long war, serving as a stretcher bearer and hospital aide from 1915 in the Dardanelles right through to the armistice in France. He received a wound in his arm and returned to Australia in 1919 with his wife, Effie. Drawing a part pension, he first spent a few months at Beerburrum before applying for a transfer to Ubobo. His son describes his father arriving at his selection with a double bed, a stove and some sheets of galvanised iron. Nevertheless, Roy Ramsay made a go of his selection, and he became something of a community leader; as President of the RSSILA he accepted the keys to the Memorial Hall in a ceremony on Armistice Day in 1928.

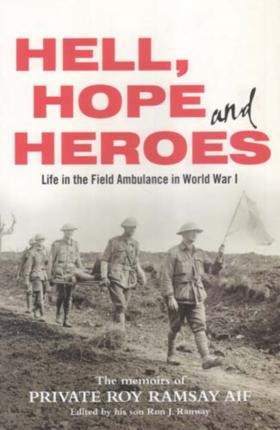

Ramsay left Ubobo in 1932. When he died his son Ron discovered a journal kept during the war, and after some editing published it in 2005 as Hell, Hope and Heroes.

William Binns served in the Royal Navy during the war. On taking up land in Ubobo he seems to have been an active member of the community. His name comes up in cricket matches, the Port Curtis Dairy Association and cotton trials, and, of course, the RSSILA. In March 1940, Binns applied for entry into the RAAF as a fitter. In his application he noted that, as the only mechanic for 50 miles he had experience in maintaining and fixing a wide range of machinery. In support of Binns’ application, Constable Marchant of Many Peaks noted: ‘He [Binns] has been known to me for over five years and he is a man of excellent character being a trustworthy, honest, sober person and highly respected citizen’.

William Binns’ grave, Gladstone (author)

William Binns’ grave, Gladstone (author)

The Central Queensland Herald reported a luncheon on 27 April 1940 for the first RAAF recruits to leave the area. Binns offered the vote of thanks to the recruitment staff and their efforts. He then went to Richmond and Laverton for training. His service record ceases abruptly in December 1940, with the National Archives closing the next eight pages exempting them from public access. By March 1941, Binns had been discharged medically unfit. On 23 April 1941, now Sergeant Marchant found the bodies of Binns and his mother under their farmhouse, the latter shot through the right eye, the former shot in the forehead. The Cairns Post reported that ‘since his return Binns had been depressed’.

The mother and son were to have visited Gladstone the next day to make final arrangements to leave their farm. Their graves are in Gladstone cemetery next to each other. William Binns’ gravestone only notes his age and his service in the Royal Navy and RAAF.

At that RSSILA annual general meeting in 1929 it is more than likely Syd Davies was in attendance. Syd was something of a celebrity, being on, according to the Gladstone Observer 99 years later, the first boat to land at Gallipoli on 25 April and being credited with capturing the first Turkish officer in the campaign. In November 1915, he was shot in the head and lost an eye.

Syd was one of the successes of the Ubobo scheme. In 1920, he built a house on portion 115, his son Hector restoring the house as a memorial to his father and the other soldier settlers. It is on the Queensland Heritage Register and still stands on the Gladstone-Monto road.

So, there we have it. One hundred years ago, Syd Davies built a house at Ubobo. Ninety years ago, Roy Ramsay left Ubobo but left us a journal that in graphic detail sets out his war that led him to there. Eighty years ago, William Binns ended his life in Ubobo, his gravestone a stark reminder of the tribulations his generation faced. A century after that Lands Department Christmas card, not much more than a memory exists of soldier settlement number 16.

* John Shield is a secondary history teacher in Gladstone, Queensland. He has written for Honest History about Text Classic’s All the Green Year, by Don Charlwood, The Cardboard Crown, by Martin Boyd, and Between Sky and Sea, by Herz Bergner, and on the treatment of Indigenous children in institutions, how to teach and commemorate Anzac, a review of a biography of Chester Wilmot, Top End Anzackery, a review of the edited diaries of William Baker Ashton, and a review of Leigh Straw’s book on the aftermath of the Great War in Western Australia.

Syd Davies’ house (Queensland Heritage Register)

Syd Davies’ house (Queensland Heritage Register)

List of Ubobo soldier settlers (Author/Boyne Valley Historical Society)

List of Ubobo soldier settlers (Author/Boyne Valley Historical Society)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.