John Shield*

‘All the Green Year: Don Charlwood between war and depression’, Honest History, 30 January 2018

When Honest History discovered the Australia Explained website and I turned to the books page thereon it gladdened my heart to see there so many Text Classics. I came up with the idea of trying to get a grip on the type of understanding of our history that a reading of the Text Classics list would furnish.

The Text Classics list is an incredibly important resource for historians. It is an attempt to ensure that core elements of Australian writing are republished and available to the public. Otherwise, these works would be lost. As Michael Heyward, Text publisher writes, ‘the effect of this neglect is to enfeeble our understanding of our history’.

The Text Classics list is an incredibly important resource for historians. It is an attempt to ensure that core elements of Australian writing are republished and available to the public. Otherwise, these works would be lost. As Michael Heyward, Text publisher writes, ‘the effect of this neglect is to enfeeble our understanding of our history’.

This is the first of what I hope will be a series of reflections on the Text Classics list. Beginning with ‘A’, I decided to start with one of my most favourite books, Don Charlwood’s All the Green Year. (Ingeborg van Teeseling reviews the book on Australia Explained.)

Of course, most Honest History readers would be more familiar with Charlwood’s great book, No Moon Tonight (1956). It is easily the greatest account of the Australian experience of Bomber Command. Charlwood’s twenty are the collective personification of wartime sacrifice, a story that has been silenced to a great extent by guilt, political correctness, and the cacophony of Anzackery. Over 4000 Australians died in that campaign.

But, despite myself, I don’t think No Moon Tonight is Charlwood’s best book. For its contribution to our understanding of ourselves I am always drawn to All the Green Year, which Text republished in 2012, nearly 50 years after its first appearance.

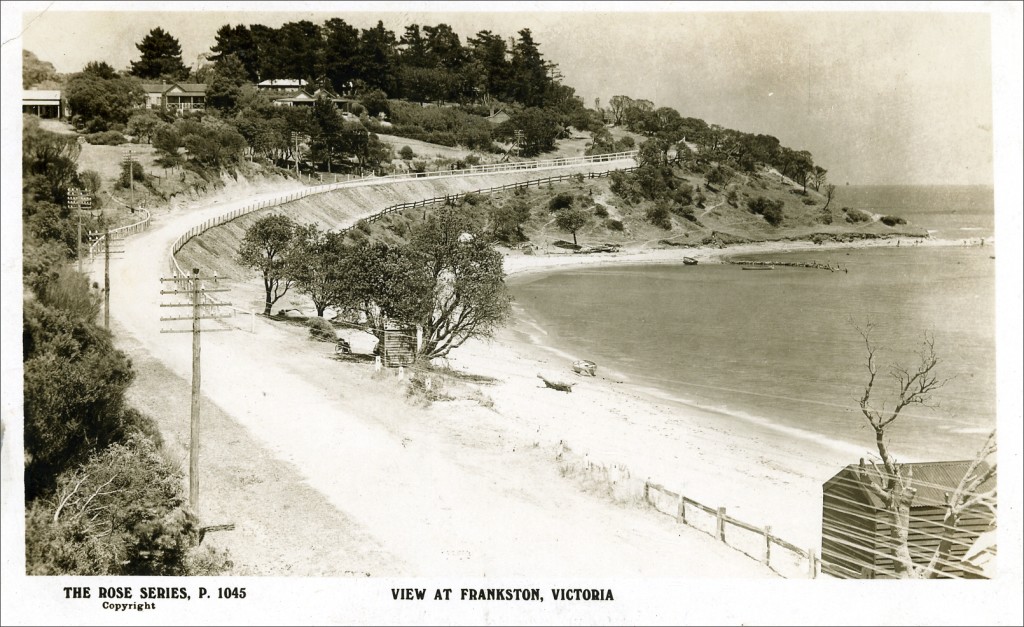

First published in 1965, ATGY is a thinly fictionalised memoir of Charlwood’s youth hanging around Frankston, Victoria, between the wars. It has always been somewhat overshadowed by Alan Marshall’s I Can Jump Puddles: similar times, the latter with a polio story – and horses, which made it the slightly sexier read.

While I will always treasure the Marshall, the Charlwood offers a broader and deeper understanding of the world in which it is set. And this is because Charlwood not only gave us his childhood to enjoy but, underneath the humour and rites of passage trope, there is one of the most authentic reflections of Australia between the wars. Seen through the eyes of 15-year-old Charlie Reeve, the Mornington Peninsula seems like a great playground.

On first glance, the book is a straightforward roman a clef. However, Charlie’s innocent eyes see and report things that point to darker forces at work. ATGY is pervaded by the Great War. In 1929 Charlie’s father is a rate collector for the council. As Charlie so eloquently puts it, ‘he had gone to this job when he had come home from the war, and he didn’t like it much’; his existence is mournful at best.

At lunchtimes, Charlie and his friend Johnno go AWOL, to sit in a pine tree in the bush beyond the school fence. Of course, it is called Lone Pine. But the greatest exponent of the war is ‘Squid’ who, way before Geoffrey Serle coined the term, maybe best understood the concept of Anzackery. Squid’s real name is Birdwood Monash Peters, and his father died at Gallipoli. The latter’s sacrifice, and the presence of his name on the town’s war memorial is the source of Squid’s identity and esteem. Charlie describes the late Lance Corporal’s photograph on the mantel looking into the Peters’ front room to emphasise the message, ‘Lest We Forget’. On Anzac Day, to quote Charlie, ‘he [Squid] always laid a wreath the size of a lifebelt and wore more medals than George V’.

So, while Squid is a comic turn, when Charlie spends an awkward evening underneath the Peters’ house, he tells us that ‘on a nail hung an AIF hat hung complete with authentic bullet holes’. This is comedic: we know that it is yet another Squid creation. But who cares? Charlie is 14. He cares, and he believes. This is how the Anzac myth was created in those far- off days.

Don Charlwood 1915-2012 (Text; photo by Yanni)

ATGY is also a novel about the Great Depression. This is a world of struggle. Despite the Lance Corporal’s self-sacrifice at Gallipoli, Mrs Peters has to play the organ at the local cinema to make ends meet. Charlie’s dad cannot take his coat off at work for fear of revealing the patches on his shirt. As Charlie points out, his mother viewed an account rendered from one of the local shopkeepers ‘as being accused of theft’.

This is a world of horse and buggy, of chip heaters and hardship. There is a wonderful moment in the book when Charlie’s dad talks to him about the ‘Merit’. Would he pass it? In 1929, is education the key? Or would Charlie be digging ditches with his friend Johnno? An atmosphere of threat hangs over the novel; it is not a coincidence that one of the great comedic moments comes during a bank auction of items at a repossessed property.

In the afterword to this edition, Don Charlwood describes a dinner table conversation in 1965, where the subjects were Vietnam and the Beatles. Charlwood was for getting out of the former, and for forbidding his daughters to attend the latter’s concert. He says that conversation was the catalyst for writing the book. War and change.

This is a book that so insightfully helps us to understand what was happening in Australia between the wars. If the bank managers could still sit in the dress circle at the pictures on a Saturday night while Charlie’s dad couldn’t afford a new shirt, well, that is how the Great Depression played out. If Charlie’s grandfather, an old sailing ship captain, could argue Bolshevism with Mr Mathias, the world was changing. The change is in the detail.

This book is honest history. To Charlie’s horror, his friend Johnno begins to discover girls. When Charlie tries to find his friend, he catches Johnno awkwardly skirting the newsagents to woo the beautiful Noreen, who works at the counter. Noreen’s father, a Presbyterian church elder, terrifies Johnno by telling him that he doesn’t think Beckett’s Budget (sensationalist journalism for the working class) is appropriate reading.

Of course, Charlie notes that Johnno, whose literacy has been suspect throughout the book, is holding the publication upside down. Building on this comedic touch, the ever-observant Charlie notes Johnno reading the news posters leaning against the shop wall as if they were ‘tremendously important’. Their content? MAGPIES FAVOURED FOR PREMIERSHIP; SCULLIN ACCUSES BRUCE.

Shortly after this, Johnno runs away and Charlie is left reflecting on the childhood that once was. As you finish the novel, you know that, in a decade, the fathers would watch their sons go off to war again.

I don’t know for sure, but I think Don Charlwood – oops, Charlie Reeve – knew his world exceptionally well. You can smell the Bay, the joy of Charlie’s childhood, complete with comedic passages that leave you breathless and in tears. But, despite his youth, Charlie is able to provide us with an authentic understanding of a world offering more despair than hope.

The million-dollar question is how much of Charlwood’s wartime journey influences the apparent naivety of Charlie’s narration? In a sense, it doesn’t matter. You can’t read the book without understanding Charlwood’s experiences. War, loss, change – a paradigm that pervades the 20th century Australian experience.

Oliver’s Hill, Frankston, c. 1920s (Pinterest)

Oliver’s Hill, Frankston, c. 1920s (Pinterest)

* John Shield is a secondary teacher, now based in Gladstone, Queensland. Previously in Darwin, he has written for Honest History on the treatment of Indigenous children in institutions; how to teach and commemorate Anzac; review of a biography of Chester Wilmot; Top End Anzackery; review of the edited diaries of William Baker Ashton; review of Leigh Straw’s book on the aftermath of the Great War in Western Australia.

Thanks so much for this excellent review, John. It’s a lovely book and your account tells us why.

Dear John,

I commend your review.

At the risk of being a nit-picker I think that we should remove the increasing Americanisms invading our language. They are under the misapprehension that the word “without” is two words, hence their abbreviation for “absent without leave”. In the Australian Army (and the British) the abbreviation is “AWL”.

Thank you.

Bill Thompson