‘A gaol story from the city of churches’, Honest History, 25 July 2017

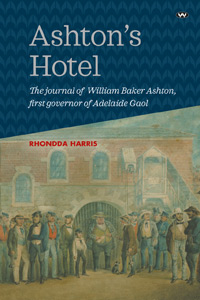

John Shield* reviews Ashton’s Hotel: The Journal of William Baker Ashton, First Governor of Adelaide Gaol, edited by Rhondda Harris

We Australians love a good gaol story. Recently I was on holidays on the mid North Coast of New South Wales. Not surprisingly, one of the main tourist attractions is a gaol. The gaol at Trial Bay was one of the last public works gaols, and then did a second gig as an internment camp during World War I. (There is a convict-Anzac link there somewhere.)

Think about our history. We love Ned Kelly, ‘Chopper’ Read, Lindy Chamberlain, Ronald Ryan. We love the literature, from For the Term of His Natural Life (1870), right up to that bicentennial gift by Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore (1986). We love the place names: H Division Pentridge, Long Bay, Port Arthur, Fremantle. It all resonates. And until Anzackery ambushed the teaching of Australian history, that subject was filled with convicts and bushrangers. We all drew a Ned Kelly Wanted poster and sang Botany Bay.

Think about our history. We love Ned Kelly, ‘Chopper’ Read, Lindy Chamberlain, Ronald Ryan. We love the literature, from For the Term of His Natural Life (1870), right up to that bicentennial gift by Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore (1986). We love the place names: H Division Pentridge, Long Bay, Port Arthur, Fremantle. It all resonates. And until Anzackery ambushed the teaching of Australian history, that subject was filled with convicts and bushrangers. We all drew a Ned Kelly Wanted poster and sang Botany Bay.

Except, of course, in South Australia. The city of churches has always held the high moral ground: no convicts here. Just really well-laid-out streets and a colony based on the Edward Gibbon Wakefield model – in his words, ‘how to make it what it ought to be’. So it was with trepidation that I opened Ashton’s Hotel. It is completely counter-intuitive for us to find a gaol in South Australia in 1839; we like to think of our gaols as nasty places with men in onesies with arrows on them. But, of course, there are bad apples in every barrel, and Mr Ashton was the man tasked to look after them. And so there was a gaol in Adelaide

Rhondda Harris has subverted the paradigm. This book puts South Australia on the gaol map. It is a strange book – and quite addictive. I kept reading excerpts aloud to my partner, who finally told me she didn’t care about the rations delivered on a Thursday afternoon. But this is a book where you want – need – to know what has happened to the Reverend, to the prisoners, even to Mr Gandy who brings the wood.

For example, 15 July 1841: ‘Received from the Store 2 Tables – 6 Chairs and 2 Small Book Presses for the Use of the Office – they did belong to the Cattle Brand Office’. So the book is big on detail. Mr Ashton was certainly committed to his journal. What is extraordinary is the amount of attention he gives the prisoners, and this is the real treasure that Rhondda Harris has unearthed. What we actually discover is that Ashton cared. And that he treated each prisoner as an individual. And that, underneath the somewhat prosaic language of the journal entries, there is compassion and humour.

Consider this, 25 January 1843: ‘Mr Moorhouse Visited the Native – he was Very Ill. I had his Irons taken off That he Might walk a little.’ We know from the previous entry that the ‘Native’ had been committed for felony and that Mr Moorhouse was the ‘Protector of Aborigines’. We first meet Moorhouse on 3 October 1839, when he visited ‘Bob’ the native for the fourth time. So, between them, Ashton and Moorhouse actually treated the Indigenous prisoners with care – but, more importantly, as individuals. Removing the irons is an unnecessary, but a humanitarian act. This is subversive writing.

Consider this, 27 and 27 June 1842: ‘Mrs Green a Prisoner Committed for Trial was Taken Ill at 6 P.M. this day. Sent for Dr. Nash and the Nurse. – At 9 She was a little better Dr Nash went home the Nurse stopped all night. At 6 O’ck this Morning Sarah Green as above Was Delivered of a Still Born female Child. Dr Nash attended.’

It stops you in your tracks. First, what had Mrs Green done? Did Ashton know she was pregnant? And finally, there is the unstated care in the text: a nurse staying all night? No wonder the Adelaide citizens dubbed the gaol a hotel. This is care strangely present in a gaol in 1842. It doesn’t fit our preconceptions.

And, finally, my favourite entry, 11 May 1840:

W’m Kay alias Yorke the Maniac was brought to the Gaol in a state of intoxication – he created a great disturbance and Several times Struck at me with a large Stick – he pulled down portions of the fence and broke Some of the boarding in the Wooden Building. Murphy, Ryan, Green, Wilson and Scott behaved extremely well, and contributed greatly to prevent the effusion of blood.

Thank God for Murphy et al. This is funny writing: poor old Ashton gets belted with a stick by William Kay, there is vandalism, but at least Ashton manages to put it in perspective and celebrates the limits of bloodletting. This is more H Division than a hotel – or is it? In this entry, the usual prison trope is replaced by measured, consistent prose. And nothing, not even a big stick, seems to rattle Mr Ashton.

William Baker Ashton (State Library of SA)

William Baker Ashton (State Library of SA)

The book is fascinating. I love the subversiveness of the writing and Ashton’s humanity towards his clientele, no matter their race, gender or mental health (Kay the maniac). If we were a ‘fatal shore’, then Ashton was one of the good guys. This is a gaol story of the highest order and we must thank Rhondda Harris for installing a new individual in the Australian prison pantheon.

Two points about the layout of the book. First, the entries are directly transcribed from the journal, which means spelling and punctuation are somewhat distracting. The upside of this, however, is authenticity: Ashton’s voice leaps out of the page and at times you just want to give him a hug.

Secondly, Rhondda Harris provides us with background and information throughout the book, interrupting the journal entries with detail on the places and people mentioned. After the first couple of these ‘backgrounders’, I must admit I stopped reading them, finding they distracted me from the Ashton experience.

This is a quite wonderful book, which covers the minutiae of a small part of Australian history. Do we really care about the provenance of Ashton’s office furniture? The answer is a resounding ‘Yes’, because, amid the minutiae, the humanity of the writer and of his human clientele is fascinating, surprising and authentic.

* John Shield is a Darwin schoolteacher. He has written for Honest History about teaching and commemorating Anzac and Top End Anzackery, and reviewed a biography of war correspondent, Chester Wilmot.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.