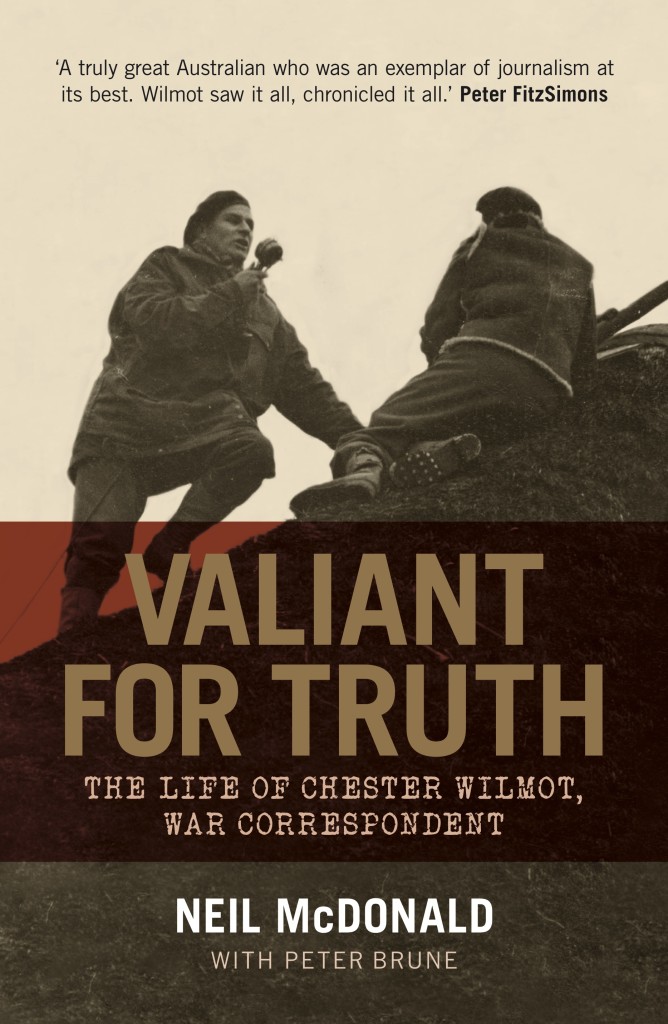

‘Valiant for Truth: The Life of Chester Wilmot, War Correspondent‘, Honest History, 12 January 2017

John Shield* reviews Valiant for Truth: The Life of Chester Wilmot, War Correspondent, by Neil McDonald with Peter Brune

There is a lovely sequence in Parer’s War, the 2014 biopic on Damien Parer, when Marie Cotter is introduced to Chester Wilmot, recently returned from Kokoda. She says: ‘I know who you are; you’re the one who tells me everything he [Parer] doesn’t’. Later she tells Parer, ‘Of course we all listen. Chester’s the first thing we talk about at work the next morning. Everyone knows about someone who’s missing or who hasn’t come back.’ (Cotter later became Parer’s wife, then widow.)

As a school teacher, it’s when my students have a Eureka moment. They suddenly realise the importance of the voice that is there – at the frontline. Wilmot’s reports were quite literally the first thing the Australian public learnt about Tobruk, the Greek campaign and Kokoda. Wilmot’s voice was the intimate connection between the war and Australia.

As a school teacher, it’s when my students have a Eureka moment. They suddenly realise the importance of the voice that is there – at the frontline. Wilmot’s reports were quite literally the first thing the Australian public learnt about Tobruk, the Greek campaign and Kokoda. Wilmot’s voice was the intimate connection between the war and Australia.

In a post-truth world, Neil McDonald’s title is a wonderful one. The tension in the book is the truth – the truth that Wilmot witnessed, and the problems that truth often causes. As well, Wilmot’s journey is a fascinating metaphor for the Australian experience between the mid-1930s and 1943. The journey is about class and privilege, about loyalty to Britain – and eventually the way in which Australia’s strategic policy was never its own.

The book begins with the famous ‘embedded’ report Wilmot filed from a 6th Airborne Division glider which flew across the English Channel in the early hours of DDay. It’s a strong place to start, because it is essentially the start of Wilmot’s third and most famous career – that of the chronicler of the British landing and advance across Europe – both as a BBC correspondent and then as the writer of The Struggle for Europe – one of the earliest and most successful examples of modern popular military history. Wilmot became an international figure, a pioneer of TV documentary – his life cut short in an aircraft crash in 1954.

It is clear from the start that Wilmot was confident, talented – and, more importantly, well connected. The son of a sporting journalist, Wilmot became school captain at Melbourne Grammar, and then studied history at the University of Melbourne. But it is his extra-curricular activities that give us a clue about his future. While studying he starred in the debating team (alongside Bob Santamaria), took an active role in student politics and was offered a job at The Star – a new afternoon paper produced by the Melbourne Argus.

By 1937, Wilmot was present at the creation of the National Union of Australian University Students – rather immodestly claiming ‘I can’t help feeling that the NUAUS is my creation’ (p. 28) – which then resolved that a debating team would undertake a world tour. And, of course, there were letters of introduction secured from Prime Minister Joseph Lyons, and on the first stop, Sydney, Wilmot managed to procure an interview with ABC General Manager Charles Moses, who provided Wilmot with an entry into the BBC training course when he got to London. For McDonald, Wilmot is on his way. (A fresh-faced 1939 Wilmot.)

Two things stand out from the tour. In April 1938, after an unpleasant visit to Austria, Wilmot and his Jewish friend Alan Benjamin returned to London. Benjamin decided to go back to Australia. Wilmot, who had been exchanging letters with Moses on cricket commentary decided to stay – in McDonald’s words because the Australians were to play England at Lords and the BBC had hinted there might be a spot on the commentary team! By September, after the Czech backdown, Wilmot noted, ‘Today I am thoroughly ashamed to be an Englishman’.

The pre-war story of Wilmot is sometimes awkwardly presented in this book. McDonald clearly believes Wilmot was foreshadowing his future, but is uncritical of Wilmot’s behaviour. As a reader, you have to accept Wilmot’s class and loyalties as a given. Hindsight is a wonderful thing – but reading the story of Wilmot in the 1930s is a glimpse into a middle-class Melbourne – a small club looking after its own and apparently immune to the hardship of the Great Depression. And very much still seeing all things British as the model. The war was to test the paradigm.

Before leaving Australia Wilmot visited CEW Bean for his blessing (?) and advice. There is no record of the meeting but McDonald believes understandably that it was a pivotal moment. From then on Wilmot accepted Bean’s mantra – the role of a war correspondent is to report, question, and if needs be, to advocate for change. The truth, especially in the third context, becomes dangerous. McDonald clearly believes Wilmot considered himself Bean’s successor.

Australian correspondents, Greece, c. April 1941, Wilmot second from left (AWM 007820/George Silk)

Australian correspondents, Greece, c. April 1941, Wilmot second from left (AWM 007820/George Silk)

Wilmot’s reporting from Tobruk was exemplary – he reported for both the ABC as well as competing for air time on the BBC with the British correspondent Richard Dimbleby. The great pleasure of this book are the large slabs of Wilmot’s reportage – and as you read you realise the language is the core of the Rats’ mythology, with Wilmot essentially creating the iconic moment in Australian military history.

At the same time, it is clear Wilmot was moving in the highest circles – and the seeds of the Blamey crisis were becoming clear. That crisis escalated after Churchill made the decision to send Australian and New Zealand troops into Greece. The complexities of that decision, and the problematic position of Blamey as the senior Australian commander within an allied force, almost inevitably led to recriminations.[1]

Possibly the most revealing moment in the story is McDonald telling us of the number of censors (Greek, British and Australian) Wilmot had to get past to file his reports. In a sense, the censorship reflected the lack of unified command, which, in due course, was reflected in the failure of both the Greek and Crete campaigns.

It is worth noting this passage from the introduction to Tobruk 1941, which Wilmot wrote in Australia after Kokoda. It is dated October 1943:

A few words of explanation may be necessary on the vexed question of the use of the term “British”. Where I have spoken at large of our forces as opposed to the enemy’s, “British” embraces all the Imperial, Dominion and Allied Troops. But wherever I have spoken of particular forces I have used it – lacking any suitable alternative – to refer only to those of the United Kingdom. This obviously does not imply that Australians regard themselves as any less British than the people of the British Isles.

I have read this passage over and over again, and I still am not quite sure, firstly, what it means, but more importantly what it reflects about Wilmot’s self-perception.

By the time that passage was written, Kokoda had been won, and the great falling out had taken place. Wilmot had undertaken to personally speak to Curtin, asking him to sack Blamey over Blamey’s treatment (sacking) of General Rowell – whom Wilmot saw as a victim of Blamey’s incompetence. Whatever the truth, it seems presumptuous, nigh on ridiculous, that Wilmot had the audacity and the self-belief that his opinion was of such importance. While the Blamey debate will apparently go on for ever, Wilmot’s part in it can only be a cameo. For McDonald, it seems the highlight of the book – Wilmot reaching the height of his influence and power.

There is also a hint in the book that Wilmot realised the real action was to be in Europe. The Struggle for Europe, arguably Wilmot’s greatest legacy, is perhaps evidence of this. For me, it seems inevitable that Wilmot, with his pedigree, loyalties and connections could not survive in a world that was rapidly changing – a world where a Curtin, not a Menzies, was prime minister – and a world where MacArthur, not Churchill, was in charge of the Australian destiny.

Gavin Long planned out the official histories of the war, with Wilmot being given the plum task of writing the volume about Tobruk and El Alamein. While Wilmot was in London, creating his post-war glittering career, Long had the Australian War Memorial lend him a set of the Bean Official History of World War I, as well as copying a number of unit war diaries to get him started. There is a lovely photo of the ‘official historians’ sitting at a meeting in Canberra in early 1954. Wilmot is seated at the table along with other distinguished gentlemen, including SJ Butlin, Paul Hasluck, and Dudley McCarthy.

Wilmot in Syria, July 1941 (AWM 008619/George Silk)

Wilmot in Syria, July 1941 (AWM 008619/George Silk)

Unhappily, for us, that voice was to be silenced – as Peter Stanley eloquently puts it ‘his loss was the greatest that the Australian Official History suffered’.[2] In a sense, though, that loss had occurred in 1943. Wilmot’s Australia was a British-focused, middle-class protected world. For the Wilmots of the world, that was never going to be the same again. The great ‘what if’ of the book is the question whether Wilmot could have taken the final Bean step, and produced an official history with an authentic Australian voice.

McDonald’s book’s is a labour of love for both himself and the Wilmot family. While there are times when one wants McDonald to be more critical, you forgive him. The great attribute of the book is the space given to Wilmot’s voice. I read some passages over and over, and you can hear the creation of the Tobruk and Kokoda stories that Peter FitzSimons would reprise half a century later. There is no doubt that Wilmot’s career lived up to the title of the book. McDonald paints Wilmot as a victim of the crisis in Australian strategy and policy in the middle years of the war – that he became a martyr to the ‘truth’. That is a valid thesis, and the book is a terrific reminder of one of the great talents Australia has produced.

[1] For Blamey, Rowell, Curtin and Wilmot, see a terrific 2006 conversation led by Bronwyn Adcock with McDonald, David Horner, Peter FitzSimons and Wilmot’s cousin Meriel Wilmot Brown on SBS. It seems to be a good summary of the arguments, which I think are still the same.

[2] Peter Stanley, ‘Gavin Long and history at the Australian War Memorial’, in Jeffrey Grey, ed., The Last Word? Essays on Official History in the United States and British Commonwealth, Praeger, Westport CT, 2003, p. 109.

* John Shield is a Darwin school teacher. He wrote about Top End Anzackery for Honest History.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.