Brett Odgers*

‘Still talking to the War Memorial? The review and regeneration of Anzac Parade, Canberra’, Honest History, 1 March 2022

[In the lead up to Anzac Day and as we confront another war in Europe, how we treat our commemorative spaces seems particularly relevant. Brett Odgers has a long interest in the design of Canberra, with particular reference to Anzac Parade and its environs. HH]

In the wake of public debate over the extensions to the Australian War Memorial it is time for the review and regeneration of Anzac Parade in Canberra. Indeed, the National Capital Authority (NCA, oversighting Canberra’s Parliamentary Triangle) is currently updating the Heritage Management Plans (HMPs) for Anzac Parade and the Parliament House Vista.

Anzac Parade is a centrepiece and icon of our evolving National Capital and it is relevant to a spectrum of political, demographic, social and cultural changes in the rapidly growing city. In this paper I discuss the history, values, functions, and past reviews of Anzac Parade. I suggest the status quo of the Parade is no longer suitable for Canberra as a city and the nation’s capital. The Parade has great potential for a higher level of excellence.

National Capital Plan and National Heritage List

Anzac Parade is on the National Heritage List ‘for cultural, aesthetic and ceremonial significance’ and the Parliament House Vista is on the Commonwealth Heritage List as ‘the central designed landscape of Canberra, expressing Walter Burley Griffin’s design vision’. The National Capital Plan enshrines Griffin’s winning plan and vision for the National Capital, especially as a city in harmony with the landscape and symbolic of the natural environment, values, ideals, history, and achievements of the nation.

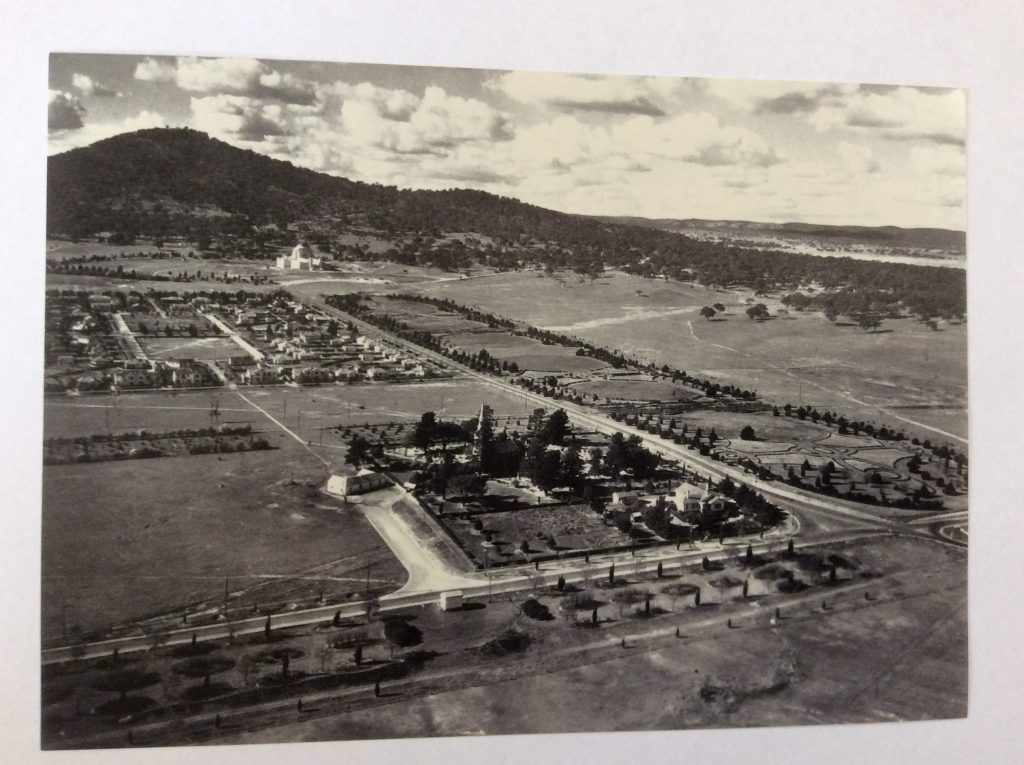

AE Macdonald, ‘Early Canberra’ (1913) Looking towards Mt Ainslie and today’s Russell; St John’s church, Reid, in the distance to the right (Canberra Museum and Gallery)

AE Macdonald, ‘Early Canberra’ (1913) Looking towards Mt Ainslie and today’s Russell; St John’s church, Reid, in the distance to the right (Canberra Museum and Gallery)

The Australian War Memorial and the Memorial-Anzac Parade are bracketed together on the National Heritage List with this inscription:

Anzac Parade, as part of the Parliamentary Vista and as an extension of the Australian War Memorial, has a deep symbolism for many Australians, and has become part of one of the major cultural landscapes of Australia. The notion of a ceremonial space of this grandeur is not found elsewhere and Anzac Parade is nationally important for its public and commemorative functions.

Professor Ken Taylor has written extensively about Canberra, the city in the landscape, along with the symbolism of Walter Burley Griffin’s design. In particular, Ken has written eloquently about Anzac Parade as a ‘landscape of memory’: ‘It is one of the great landscape axes of the world. The serendipitous outcome is that Griffin’s Land Axis maintains its national symbolic status in a dual way. One as part of Griffin’s ideal city, the other as national memory.’[1] Sally Barnes, NCA Chief Executive, says the Australian War Memorial ‘talks to’ Anzac Parade (page 3).

Origins and reviews of Anzac Parade

At the direction of Griffin and Charles Weston, pioneer Canberra forester, Griffin’s plaisance or parkway was planted with trees and shrubs and walkways. The site for the Australian War Memorial was determined by the Federal Capital Advisory Committee in 1923. Griffin’s Prospect Parkway was renamed Anzac Park in 1928 by the Canberra National Memorials Committee.

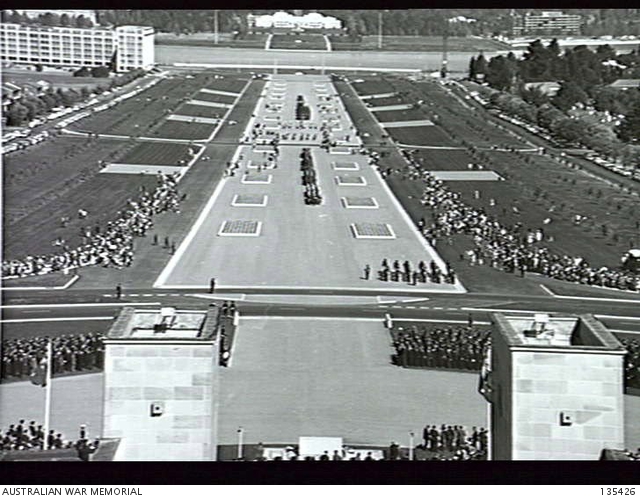

The National Capital Development Commission (NCDC) explored ‘new visions’ for Anzac Parade in the 1960s and – for the 50th anniversary celebrations of the Gallipoli Landing in 1965 – it reconstructed and renamed the ‘processional way’ Anzac Parade/Anzac Park. Around this time, too, Clough and Harrison of the NCDC replaced Weston’s trees with Tasmanian Blue Gums and New Zealand shrubs in planter boxes.

In the early 1990s, the National Capital Planning Authority (NCPA) proposed a radical redesign of Anzac Parade. An open competition yielded ‘four finalist teams of highly experienced Australian architects, landscape architects and other designers’.[2] The winning Daryl Jackson Architects plan displayed intensive parklands while keeping the open Land Axis vista. Anzac Parade was assessed to be ‘a place that needs to be engaged with directly – to walk, look and reflect’.

That period now looks like a missed opportunity, as there have no more reviews or redesigns since. In September 1991, NCPA held a ‘Seminar on Landscape in the Central National Area’ (with architects and landscape architects Giurgola, Jackson, Johnson, Reid, Stretton, and Weirick) that led to the Central National Area Design Study report, Looking to the Future (1995).[3]

The Griffins’ original preliminary plan 1913 (Inside Story/NLA)

The Griffins’ original preliminary plan 1913 (Inside Story/NLA)

Looking to the Future begins with ‘Expanding the Vision’, referring to Griffin’s Land Axis as a ‘symbol for the city in the landscape’ with the Water Axis as a ‘symbol for nature in the city’. The report concluded that ‘Anzac Parade should continue as the nation’s Spiritual Place, but not exclusively in a military sense. Areas of achievement such as the arts, culture, democracy and justice could also be celebrated here.’[4] One of the finalists in the earlier Redesign competition proposed a ‘Peace Square’ and another a ‘Place for Great Australians’.

The 1991 Seminar discussed Daryl Jackson’s winning design for Anzac Parade. Jackson argued ‘landscape alone cannot assume the burden of meaning and symbolism we expect of the National Capital’. He designed parterres, walks and garden beds on the ‘undistinguished strip’, imagery of the States in the Federation and attractive parkland inviting ‘people, concerts, meetings, gatherings, festivals’.

Original Griffin Plan

At the NCPA Seminar James Weirick highlighted Griffin’s plan, the Prospect Parkway with Casino at the base of Mount Ainslie, a parkland plaisance along the Land Axis, derived from Frederick Law Olmsted Senior’s Midway Plaisance in Chicago, and the Casino, modelled on Frank Lloyd Wright’s Midway Gardens, drawing people for relaxation, recreation, concerts, and popular entertainment. Professor Weirick was not sure we needed to continue the solemnity of the War Memorial throughout the Parade and regretted the ‘desert-like emptiness and lack of people’.

At the southern end of what is now Anzac Parade, between the Lake and Constitution Avenue (the ‘Municipal Axis’), Walter and Marion Mahony Griffin famously depicted a stadium (recessed so as not to interrupt the Land Axis vista), four museums (including the arts), zoological gardens, Opera House, theatre, baths and gymnasia. In his Report Explanatory of October 1913 Griffin places these local recreational, relaxation, cultural, arts, educational and sporting activities on and beside the Land Axis in ‘public gardens a showplace of the city, a tributary to the homes of people, with maximum accessibility, culminating in the Casino.’ He also envisaged ‘commemorative monuments’.

The Griffins did not design a formal avenue or imagine a marching strip. They were certainly pacifists during their time in Australia. Photos of Charles Weston’s garden layout of the parkway (probably at Griffin’s direction) show a picturesque setting with tree plantings predominantly informal and a strong evergreen component, a series of spaces, and varied, aligned plantings in a lace-like pattern, but still keeping the open vista consistent with the remainder of the Land Axis through Parkes Place.

Like Griffin’s Capitol concept for Capital Hill, the Prospect Parkway and Casino plans provide a wealth of alternative scenarios to the status quo of Anzac Parade. The Griffins’ vision and the subsequent NCPA reviews provide inspiration and options to enhance the Parade.

The Griffins, c. 1920 (SMH/NLA)

The Griffins, c. 1920 (SMH/NLA)

Sacred site and other military monuments and memorials

The military hegemony in Anzac Parade seems less suitable nowadays in the light of shifting notions about national identity, the militarisation of Australian history, patriotism, values, sentiments, and symbols. Professor Joan Beaumont told the Canberra Times in 2018 that ‘dedicating Griffin’s symbolic Land Axis to military service speaks volumes about the place of war in Australia’s political culture and rhetoric. Few capital cities in the world have such prominent design.’

There have been plenty of indications of resistance to more military memorials – for example, in this notable piece from Jack Waterford in November 2018 and in the diary of the Heritage Guardians group recording its (unsuccessful) campaign against the $500m extensions of the Australian War Memorial – in favour of more diverse and representative objects of commemoration.

Stakeholders and users of Anzac Parade

Anzac Parade is not regularly used for commemorative purposes. There are only two annual ceremonial days: Anzac Day and Remembrance Day. The crunch of marching boots is rarer still as marching bands have been banned in favour of broadcast marching music for the Veterans’ March on Anzac Day (courtesy the ACT Branch of the RSL).

On Anzac Day, all the marchers and amenities take up only half of the Parade. The Parade also hosts low usage and rare joint programs with the War Memorial.

Anzac Parade’s main functions are vehicle traffic, vistas, conservation of the Land Axis and setting of the War Memorial, memorials of battles and military service, open space, tourism, and occasional commemoration. It continues, however, to serve an overarching political function, used by politicians in particular to capitalise on Anzac and the armed services. This is increasingly seen as a lopsided view of our national identity and history.

In October 2018, the NCA refused permission for a Silent Vigil by the Independent and Peaceful Australia Network, supported by Medical Association for the Prevention of War, Quakers, and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, to mark Remembrance Day on 11 November. A spokeswoman for the NCA told the media that ‘Anzac Parade had been reserved exclusively by the war memorial’. The Memorial, however, denied any part in the NCA’s decision.

Accessibility is non-existent as the central strip is virtually bare and the roads carry a lot of dangerous traffic. The Parade is not inviting to people, except for the war memorials and then selectively. A Canberra Times correspondent wrote, ‘It’s scary. Every time I cross it, I expect to be mown down by a whiff of grapeshot.’ [5]

Spaces on the Parade are reserved for more memorials while public opposition to more memorials is becoming insistent. The distinction between ‘necessary’ and ‘chosen’ wars could limit the field and the number of new memorials. The spirit of the nation, the achievements, identity, values, and global status are recognised increasingly without reliance on military service, battles, and Anzac.

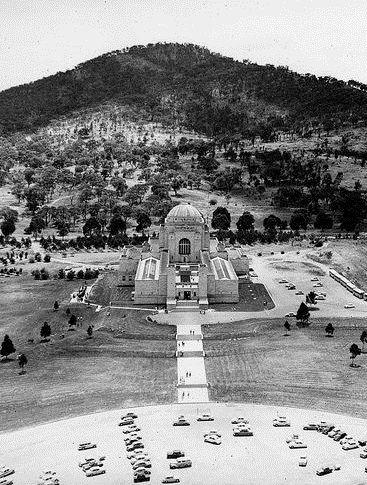

War Memorial and what is now Anzac Parade, with the suburb of Reid to the left, 1940s (author)

War Memorial and what is now Anzac Parade, with the suburb of Reid to the left, 1940s (author)

During the war memorials controversy of 2007-12 the NCA went along for a time with the conventional military devotion by supporting strongly the proposal for huge World Wars I and II memorials on the Lake foreshore on Rond Terrace, over the road in line with Anzac Parade. Ultimately, the proponents were forced to abandon the project in face of community and, eventually, War Memorial Council disapproval. By this time, the NCA had become opposed also.

At the time, the former NCDC Commissioner Tony Powell said that the chosen site ‘is not in accordance with the NCA’s stated policy’.[6] Incredibly, the NCA’s current Project Brief for review and update of the Parliament House Vista Heritage Management Plan (2019)[7] includes: ‘Additional requirement no. 1. Develop principles/policy to guide future development, such as uses for Rond Terrace e.g., installation of memorials, events etc.’ The NCA thus ignores the determination that the Rond Terraces should be free of memorials but continue to be the site for community recreation, sporting, exhibition and festival activities.

Parade Stakeholders include future generations. The latter are already rapidly arriving as residents along Constitution Avenue, in Section 5 Campbell and prospective redevelopment in Reid. Parklands and open space are diminishing in the city and inner north suburbs. The location and nature of ‘the processional way’ is incongruous in this rapidly developing scenario, which is more or less the residential density, areas and amenities envisaged by Griffin. The NCA seems more concerned with ‘screening’ such housing than restoring or creating valuable parkland and amenity for a burgeoning population.

One notable citizen is Chris Latham. As Director of the Canberra International Music Festival for some years but especially in Centenary Year 2013, he employed with great effect the Griffins, the geometry and symbolism of their Plan, for the themes, graphics and ‘key nexus points’ for the concerts. As Musical Artist in Residence at the War Memorial, Chris produced the Gallipoli Symphony (2015) and The Diggers’ Requiem (2018), both collaborations by various Australian composers.

In a 2019 paper on revisiting the Griffins’ vision[8] Revisiting the Griffins’ Vision (2013), part of fundraising for performances of the Symphony and Requiem, Chris juxtaposed the War Memorial with an ‘arts precinct’ reviving Griffin’s vision and plan for the arts, music and theatre in Anzac Parade, to ‘enable catharsis and healing, and to empower the movement towards a lasting peace in the world’. Chris incorporated Griffin’s intentions in The Diggers’ Requiem and he has presented his thesis at a number of talks around Canberra and in the media.

Landscape values, aesthetics and symbolism

The NCA’s Heritage Management Plans incorporate abundant data on the existing purposes and uses of the Parade but do not differentiate between the gravel parade ground and the actual memorials spaced along the adjoining Anzac Park tree-lined streets, which define the 200 metre wide and 1.5 kilometre long original Griffin Land Axis Prospect Park. The data is also limited by positive questionnaires rather than negative assessments, such as criticisms of lengthy unrelieved emptiness, bare of any features other than war memorials, crushed red house bricks and an exclusive, rarely used parade ground.

There is a parallel with the Black Mountain Tower. The NCDC was overruled by the Postmaster-General in 1974 and so suffered a big, unnecessary, nondescript, conventional structure on a prominent and beautiful inner-city mountain, which distracts attention from and distorts the geometric, symbolic aesthetic layout of the planned National Capital.

War Memorial, looking North, c. 1950 (Pinterest/AWM)

War Memorial, looking North, c. 1950 (Pinterest/AWM)

There is a high level of recognition of both the Tower and Anzac Parade as Canberra signature icons; it is difficult to find data on the aesthetic character of either. It is of interest that a recent public debate in the Canberra Times attracted a significant number of letter-writers in favour of demolishing the Tower, instead of a proposed renovation. In my view, neither Anzac Parade nor the Black Mountain Tower have redeeming aesthetic qualities, apart from their landscape settings, although the ACT Heritage Places Register notes that ‘a ceremonial space of the Parade’s grandeur is not found elsewhere in Australia’.

For me, the long, red gravel parade strip of Anzac Parade is incongruous and ugly from all angles, especially from above and afar, a blemish and a distraction compared with the alternatives conceived by Griffin, Weston and expert reviews in the early 1990s, of public walkways, native flora, gardens and parkland. These alternatives could enhance the symbolism of the Australian natural environment, ethos and identity, the Land Axis and the Parliament House Vista, which is a vast area that presents great potential for development as impressive landscaping with parkland, gardens, walkways, accessibility, relaxation and recreation, culture and the arts, and to enhance the Land Axis with its national symbolism.

The present presumed military parade ground, processional, commemorative and ceremonial strip does not serve the nation well as an icon. It is a lengthy, bare space, ugly, with no redeeming aesthetic qualities apart from the landscape setting. It is a distraction from the Central National Area and the Griffins’ vision.

Ken Taylor and the late Aldo Giurgola have both drawn attention to the potential of the Parade to convey the elements of the Australian bush and wildlife. Scientifically, it is an urban wildlife corridor. Anzac Parade is presently ‘replete with symbols’ but has great potential for non-military features and non-military purposes and events.

It would not be difficult to redesign, relandscape and regenerate Anzac Parade while retaining a marching parade. The Parade is 1.5 kilometres long and 200 metres wide. The northern intersecting side streets, Blamey Crescent, Currong Street-Geerilong Gardens and East and West Anzac Parks, allow ample space for marching groups to form up and into the Anzac Day march as it is underway. The impending rebuild of the approach and forecourt of the Memorial enlarges these options. The commemorative memorials would be unaffected and given improved settings, access and safety.

Responsibility, approvals and accountability

Through its Joint Standing Committee on the National Capital and External Territories (JSCNCET) the Australian Parliament holds the NCA accountable for Canberra’s development as the National Capital. The statutory Canberra National Memorials Committee (CNMC) approves the location and character of new memorials and how they address the Capital’s national memorial landscape and, through the NCA, maintains and enhances public commemorative sites, monuments and memorials. There is a strong case for both the JSCNCET and the CNMC to examine Anzac Parade, especially in the context of the War Memorial’s expansion.

Anzac Parade and its environs have fascinating and stimulating history and prospects. During the various Griffins’ Canberra tours conducted by the Walter Burley Griffin Society, the Griffins’ vision for Anzac Parade has never failed to register interest and delight with tourists and Society members alike.

Beyond the NCA’s current status quo-reinforcing updates of Heritage Management Plans, Anzac Parade warrants a review of its heritage values and potential for regeneration. With the increasing population and density of Canberra, high expectations for its role as the national capital and heritage conservation of Griffin’s Land Axis, there are contemporary imperatives to diversify and enhance the uses of this national land.

1965, 50th Anzac Day and opening of Anzac Parade, from steps of Australian War Memorial (AWM)

1965, 50th Anzac Day and opening of Anzac Parade, from steps of Australian War Memorial (AWM)

*Brett Odgers FEIANZ, member Walter Burley Griffin Society.

[1] Ken Taylor, ‘Our cultural landscapes’, Heritage in Trust (National Trust ACT), Spring 1999, pp 3-4.

[2] NCPA, Looking to the Future: Central National Area Design Study, Canberra, 1995.

[3] Looking to the Future.

[4] NCPA, Landscape in the Central National Area: Seminar Proceedings, 12 & 13 September 1991, Canberra, 1991.

[5] David Walker to the editor, Canberra Times, 20 February 2011.

[6] Tony Powell to the editor, Canberra Times, 6 February 2012.

[7] NCA, Parliament House Vista Heritage Management Plan – NCA Project Brief RFQ 19/232 to Consultant: Special Requirements related to the Parliament House Vista (reprinted in Appendix B, Anzac Parade Canberra Heritage Management Plan Draft 3, Canberra, 2020).

[8] Chris Latham, Memory, healing and the Arts in the Griffins’ Vision: revisiting their vision a century after the Great War, Ainslie Arts Centre, Braddon ACT, 6 November 2019.

View of the Memorial from Anzac Parade, November 2021 (supplied)

View of the Memorial from Anzac Parade, November 2021 (supplied)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.