John Myrtle*

‘Weathering the Mallee over nearly two centuries’, Honest History, 8 November 2019

John Myrtle reviews Mallee Country: Land, People, History by Richard Broome, Charles Fahey, Andrea Gaynor and Katie Holmes

Mallee Country records a project on the ecological and human history of three large bands of land across the southern part of Australia, mostly in South Australia, New South Wales and Victoria, but also a strip in the south of Western Australia. The project began at La Trobe University in 2010 and, supported by a grant from the Australian Research Council, involved a team from La Trobe and the University of Western Australia.

Mallee country’s average annual rainfall varies from 600 mm in the west to 300 mm in the east.[1] The book describes the Mallee as ‘the semi-arid zone in which mallee eucalypts predominate, or where they grew in the past before the radical transformation of their habitat into dry-farmed wheat lands’.[2] The word ‘mallee’, adopted by 19th century settlers, derived from an Aboriginal word for eucalypts, ‘mali’, used for eucalyptus dumosa, a species that is predominant in the Victorian Mallee.[3] The Macquarie Dictionary incorporates ‘mallee’ in a number of terms. Apart from the Mallee region, we have ‘mallee bull’ (‘as strong as a’); ‘mallee roller’ (heavy roller used for flattening mallee country), mallee roots (roots of eucalypts, used for fuel) and mallee fowl (found in dry inland scrub areas).

Mallee country’s average annual rainfall varies from 600 mm in the west to 300 mm in the east.[1] The book describes the Mallee as ‘the semi-arid zone in which mallee eucalypts predominate, or where they grew in the past before the radical transformation of their habitat into dry-farmed wheat lands’.[2] The word ‘mallee’, adopted by 19th century settlers, derived from an Aboriginal word for eucalypts, ‘mali’, used for eucalyptus dumosa, a species that is predominant in the Victorian Mallee.[3] The Macquarie Dictionary incorporates ‘mallee’ in a number of terms. Apart from the Mallee region, we have ‘mallee bull’ (‘as strong as a’); ‘mallee roller’ (heavy roller used for flattening mallee country), mallee roots (roots of eucalypts, used for fuel) and mallee fowl (found in dry inland scrub areas).

The early chapters of the book describe the occupation of mallee lands by Aboriginal people over many millennia and describe the means of fostering a sustainable living from the land. Over time there were significant climatic changes, for example, prior to 35 000 BP, the Mallee region was wetter than now and water was readily available. But, between 25 000 and 18 000 BP the climate dried and the occupants needed to retreat to areas of permanent water. Mallee Country spells out how fire was used to clear land ‘through difficult country’, to create grazing pasture for kangaroo, and to drive smaller animals from the bush and increase the availability of food such as yams.[4]

It is likely that Charles Sturt was the first white man to see the Mallee, when he skirted its northern boundaries on his voyages of discovery down the River Murray in 1830. The first white man to penetrate the Mallee was Edward John Eyre, who drove a herd of cattle from Port Phillip to the Northern Grampians in May 1838.[5] ‘When Europeans first encountered the Victorian Mallee, they were dismayed by what they found [and written] descriptions abound of its waterless, featureless scrub, and the monotony of its landscapes … Many horses died of thirst and exhaustion, and their riders, mostly explorers or surveyors, only narrowly escaped a similar fate.’ It was ‘both unknowable and alienating to European sensibilities’.[6]

Later in the 19th century, the Victorian Government led the way in the opening of mallee lands to closer settlement. South Australia followed suit and the mallee roller and stump-jump plough were used for economic clearing for grain growing.[7] For wheat growers, there were some good years in the 1880s, but the Federation Drought from 1895 to 1903 ‘brought dust and desolation to the golden fields’ and the average rainfall in mallee lands dropped by two-thirds.[8]

In spite of these setbacks, in the 19th century there were people with appropriate work experience and determination who did succeed in mallee country. The diaries and personal papers of Charles William Coote, held in Melbourne University Archives, provide numerous insights into the life of this farmer of wheat, oats and sheep in the Quambatook area of Victoria on the southern fringe of the Mallee. In his youth, Coote had worked on his family’s farm. He struggled in the early years, but eventually diversified and became well established. He was prominent in local farmers’ associations and took an active interest in local affairs such as irrigation, prices and transportation, as well as State politics. His papers include farming account books from 1896 to 1917 and diaries from 1900 to 1955.

On the negative side of the ledger, Mallee Country records that ‘in the history of Australian land settlement few schemes have the notoriety of the soldier settlement schemes introduced to repay a “debt of honour” to men who had served in the Great War’.[9] The book gives a number of instances from the Victorian Mallee in the 1920s and 1930s, where settlers not only battled the conditions but also struggled to meet the costs of clearing, improving and stocking their land.

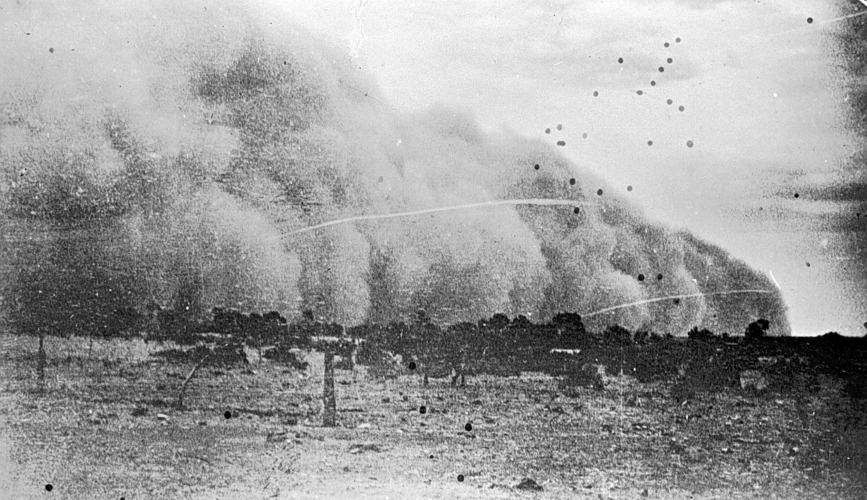

Dust storm in the Mallee, Mittyack, Vic., 1928 (Museums Victoria; Reverend Muller)

Dust storm in the Mallee, Mittyack, Vic., 1928 (Museums Victoria; Reverend Muller)

One major problem at this time was that many of the returned servicemen had no practical farming experience and were always likely to struggle to establish their allocated blocks. Marilyn Lake, writing about soldier settlement in the Victorian Mallee, has a number of case studies of those who tried, but eventually failed. William Bellamy, who had been a wireless operator with the Australian Flying Corps in France, had a well-paid job in Melbourne but decided to try his hand. He had little capital and was allocated 720 acres of unimproved land near Ouyen. By 1933, he was defeated and he surrendered his wheat block with the words, ‘After eleven years of struggle I went out with nothing’.[10]

The epilogue to the book includes an extract from a poem, ‘Dust’, by Judith Wright. The poem’s opening lines epitomise the struggle of European settlers in mallee country in the aftermath of land clearing and drought that threatened productive farming.

This thick dust, spiralling with the wind,

Is harsh as grief’s taste in our mouths

And has eclipsed the small sun.[11]

According to the book, the first major dust storm in the Victorian Mallee was in November 1902. Howling winds carried in ash and soil from the South Australian Mallee.[12] Removal of the mallee scrub accentuated the mobility of sand ridges. Dust was one of the worst features of the Mallee, with soil erosion looming large in both sociological and economic terms, something emphasised in an important sociological report on Victorian wheat farming published in 1945.[13]

The poet John Shaw Neilson struggled to make an impact in the Mallee.

Never as idlers were their full days spent,

Down the dark ages did they strive and toil …[14]

Neilson’s family had taken up a selection in 1895. Desperately poor, they frequently needed to raise money by undertaking arduous work for others, clearing and rolling the bush and grubbing out roots. Neilson himself was not physically robust and his entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography records that he spent much of his life working in casual labouring jobs all over Victoria and parts of New South Wales, some 200 jobs in thirty years.

There are numerous published records of the struggle of settlers and their families, all seeking to establish themselves in the harsh Mallee environment. Florence Beaton’s A Women’s Work: The Story of a Mallee Farmer’s Wife from 1913, describes settlement at Yatpool, not far from Red Cliffs, and near a siding on the Melbourne-Mildura railway line.[15]

With such a major research project, there is much more to Mallee Country than the mainly historical issues covered in this review. For example, the concluding section, ‘Living with the Mallee, 1983 to the Present’, covers important economic, environmental and cultural issues, such as climate change and land diversification. The research for the book concluded in 2018 and draws attention to the global difficulties at that time with extreme weather conditions, a situation that is showing no sign of relief with Australia’s worst drought in recorded time.

A dust storm rolling over Ouyen, Vic., 1928 (Museums Victoria; Arnold Studio)

A dust storm rolling over Ouyen, Vic., 1928 (Museums Victoria; Arnold Studio)

Two years ago, Monash University Publishing published another important eco-history on the impact of drought in Australia, Slow Catastrophes: Living With Drought in Australia, by Rebecca Jones.[16] Like Mallee Country, this earlier work is based on impressive scholarship. The photographs in Slow Catastrophes are superior, however, to those included in Mallee Country. It is regrettable that a major academic work has been compromised with poor quality illustrations. Putting that limitation to one side, Mallee Country: Land, People, History is an impressive ecological and cultural history which provides a valuable record of a major research project.

* John Myrtle was principal librarian at the Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra. He has produced Online Gems for Honest History, drawing upon his extensive database of references and including notes about the 1940 Canberra plane crash and the 1937 Stinson crash in Queensland, and has written a number of book reviews for us (use our Search engine), most recently of a biography of aviator, Charles Ulm, and a study of Edward St John QC. He has also explored the history of the Arthur Norman Smith lectures in journalism.

[1] Ruth A. Morgan, ‘Farming on the fringe: Agriculture and climate variability in the Western Australian wheat belt, 1890s to 1980s’, James Beattie, Emily O’Gorman & Matthew Henry, ed., Climate, Science and Colonization: Histories from Australia and New Zealand, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2014, p.161.

[2] Mallee Country, p. x.

[3] Ibid., p. ix.

[4] Ibid., p. 19.

[5] Aldo Massola, ‘Aborigines of the Mallee’, Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria, 79, 2, 1966, p. 267.

[6] Katie Holmes & Kylie Mirmohamadi, ‘Howling wilderness and Promised Land: Imagining the Victorian Mallee, 1840-1914’, Australian Historical Studies, 46, 2, 2015, pp. 191-92.

[7] Mallee Country, p. 102.

[8] Ibid., p. 12.

[9] Ibid., p. 146.

[10] Marilyn Lake, The Limits of Hope: Soldier Settlement in Victoria 1915-38, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1987, p. xiii.

[11] Judith Wright, ‘Dust’, Meanjin Papers, 4, 1, 1945, p. 20.

[12] Mallee Country, p. 127.

[13] Alan J. Holt, Wheat Farms of Victoria: A Sociological Survey, University of Melbourne, 1946; see page 145 for some meteorological data.

[14] John Shaw Neilson, ‘The good men made the wine’. First published Meanjin, 101, 24(2), 1965, p. 222.

[15] Florence Beaton, A Woman’s Work: The Story of a Mallee Farmer’s Wife from 1913, Sunnyland Press, Red Cliffs, Vic., 1985.

[16] Monash University Press, 2017

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.