John Myrtle*

‘Charles Ulm’s vision and determination made him a pioneer of Australian aviation’, Honest History, 20 August 2018

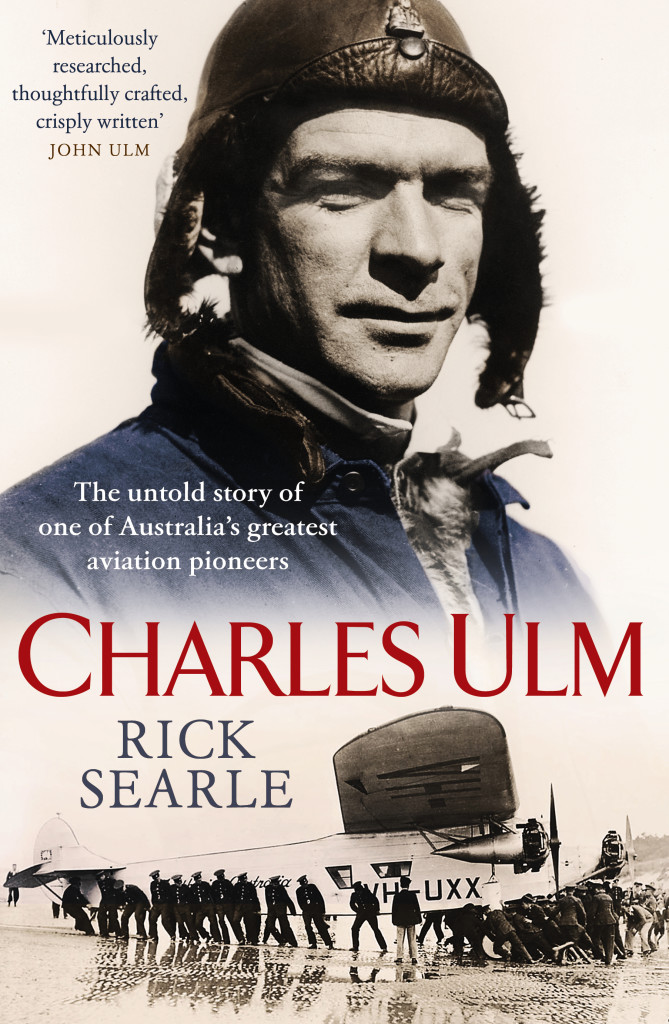

John Myrtle reviews Charles Ulm: The Untold Story of One of Australia’s Greatest Aviation Pioneers by Rick Searle

More than 80 years after the death of Charles Ulm, it is remarkable that only now do we have a detailed biography of this significant pioneer of Australian aviation. It comes in this book by Rick Searle, a freelance writer and film maker.

More than 80 years after the death of Charles Ulm, it is remarkable that only now do we have a detailed biography of this significant pioneer of Australian aviation. It comes in this book by Rick Searle, a freelance writer and film maker.

One reason for this gap is that Ulm’s name has often been associated with and over-shadowed by that of Charles Kingsford Smith, who is generally acknowledged as the pre-eminent pioneer Australian aviator. Historically, Ulm was not a pioneer aviator but, as Searle’s biography demonstrates, he had vision and determination that established him as a genuine pioneer of Australian aviation.

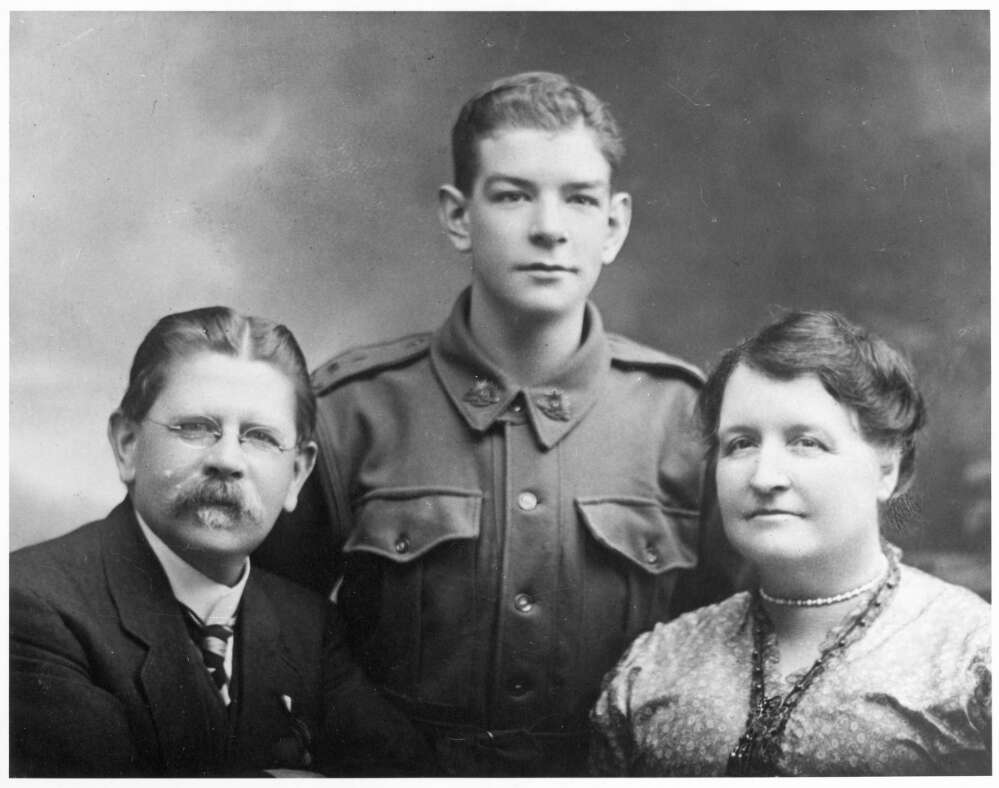

Charles Ulm was born in Melbourne on 18 October 1898. While he was still young his family moved to Sydney. He was a restless spirit and left school at the age of 14, commencing work as a clerk in a firm of stockbrokers. Such was his restlessness that, when the war came in 1914, he forged the signature of a parent and joined up. He landed at Gallipoli in April 1915, was wounded and returned to Australia. Eight months later he re-enlisted, this time with parental approval, and was deployed to France, where he was seriously wounded and evacuated to England for recuperation. He claimed to have undertaken flight training there, but there is no official record of this.

Returning to Australia, Ulm had no verifiable flying experience and was not a licensed pilot. However, the war had shown the opportunities for aviation. Ulm was soon involved with various ventures, initially regional services in New South Wales. By 1927, he became aware of Interstate Flying Services, a company set up by two experienced wartime pilots, Kingsford Smith and Keith Anderson. The company was struggling but Ulm became business manager and reinvigorated its operations. Eventually, Kingsford Smith and Ulm fell out with Anderson, a split fuelled by Ulm’s uncompromising approach to the business.

The 1927 achievement of Charles Lindbergh in flying single-handed from New York to Paris galvanised other aviators to contemplate significant long distance flights, such as the journey from the United States to Australia. The Pacific crossing was a daunting prospect with pinpoint navigation required over long stretches of ocean. The planning and execution of the historic 1928 flight from San Francisco to Brisbane by Kingsford Smith and Ulm, with the navigation and communications support of Harry Lyon and Jim Warner, is vividly related in this biography.

Ulm and parents, 1914 (NLA)

Ulm and parents, 1914 (NLA)

There were three legs in the trip: San Francisco-Hawaii; Hawaii-Fiji, and Fiji-Brisbane. The middle leg was the most perilous as the longest non-stop overwater journey yet attempted. The Southern Cross aircraft had to be modified with fuel tanks carrying four tons (over 3500 kilograms) of fuel. A photograph in the book shows the rear cabin with wicker chairs for Lyon and Warner, with a massive fuel tank blocking all access between the pilots and their support crew. The men communicated by attaching notes to a fishing rod pushed between the fuel tanks.

Kingsford Smith’s skill as a pilot was critical to the success of the flight, while Ulm was a subordinate co-pilot. His real importance was his planning and organisational skill. He negotiated sponsorship and funding – and feuded along the way with various individuals and groups who he felt were threatening the project. The original intention had been for Kingsford Smith and Ulm to fly the final and shortest leg of the journey, Fiji-Brisbane, without Lyon and Warner, thus concluding the journey with an all-Australian crew. This led to an angry exchange between Ulm and Lyon and, while Lyon and Warner eventually resumed as part of the crew for the final leg, they had to sign a restrictive and patronising legal agreement. ‘Ulm’s mercenary, legalistic approach [in settling this dispute] had taken a sheen from the whole enterprise (Searle, p. 130).’

With the completion of the trans-Pacific crossing Kingsford Smith and Ulm were feted and amply rewarded. They received honorary commissions from the RAAF and payments from the federal and New South Wales governments. An American sponsor, Captain Allan Hancock, the owner of the Southern Cross, would gift the aircraft to Kingsford Smith and Ulm and settle outstanding debts from the flight.

Capitalising on the success of the flight, Ulm’s ambition was to build an airline to link the capital cities of Australia. The establishment of Australian National Airways (ANA) was announced in December 1928. The Sydney-based company had a nominal capital of £200 000, with Kingsford Smith and Ulm as salaried joint managing directors.

At first, ANA’s service (Brisbane-Sydney) was popular, and a daily mail service was a useful sideline. The public were attracted to a service associated with Kingsford Smith and Ulm, but Kingsford Smith was quickly bored with regular line flying and removed himself from the airline’s operations. It was Ulm who drove the operations and administration, hired the pilots and other staff, and promoted the service. Kingsford Smith’s lack of interest and involvement meant his and Ulm’s careers would follow different paths. In the words of one writer, ‘by November 1931 there were signs of disintegration in the partnership of Kingsford Smith and Ulm … It is clear that their once-cherished relationship had been souring for some time.’[1]

And there were dark clouds ahead for ANA. On 21 March 1931 an ANA aircraft, the Southern Cloud, disappeared on a flight from Sydney to Melbourne. All on board perished; the wreckage, as well as the bodies of the pilot, co-pilot and six passengers, remained undiscovered for 27 years.

The loss of the Southern Cloud was a body blow for the fledgling service, and there were other challenges for the airline, with increasing competition in passenger and mail services from other operators, particularly as the Great Depression impacted on business confidence. In February 1933, ANA shareholders voted to wind up the company and dispose of its assets.

ANA’s demise shook Ulm. Though his personal finances were depleted he continued to work on his next aviation venture, a trans-Pacific air service from Sydney via Auckland and Fiji to Honolulu. In September 1934, he registered a new company, Great Pacific Airways, with nominal capital of £500 000 and himself as managing director. Despite having little working capital, the company acquired an Airspeed Envoy aircraft. On 3 December 1934, the plane, named Stella Australis, took off from San Francisco for Honolulu with Ulm as chief pilot and a relatively inexperienced co-pilot and navigator-communications operator.

Ulm and Prime Minister JA Lyons (centre), 1934 (NLA)

Ulm and Prime Minister JA Lyons (centre), 1934 (NLA)

The aircraft never reached Honolulu and all three men perished. After Ulm’s death there was criticism of his final trans-Pacific venture, but Ernest (later Sir Ernest) Fisk, a supporter of Ulm and chairman of Great Pacific, spoke out in Ulm’s defence, stating that his objective had been ‘both patriotic and businesslike’.

The short entry for Ulm in the Australian Dictionary of Biography suggests that ‘Ulm was regarded with considerable affection by those who worked with him’. While this may have been true for a small group of close associates, the reality is that, for a larger number of pilots and other employees, he was hard driving and uncompromising in his personal relations. Throughout his life Ulm seems to have been a restless individual who had an obsession with furthering his aviation interests, often to the detriment of personal relationships.

Interestingly, both Ulm and Kingsford Smith had a close relationship with the controversial Sydney solicitor Eric Campbell, who was the founder and principal behind the New Guard movement in New South Wales in the 1930s. Campbell was Ulm’s personal and business lawyer and Ulm in turn seems to have strongly supported Campbell’s New Guard activities. The New Guard memoirs of Eric Campbell record a communication from Ulm: ‘The boys liked the part about kicking out Communists instead of being kicked out by Communists – you can count on both Smithy and me’.[2]

For researchers, there is ample evidence of Ulm’s organisational skills and his flair for promotion and publicity. Libraries such as the National Library of Australia and the Mitchell Library in Sydney, together with the National Museum of Australia, have considerable holdings of his personal papers, photographs and other documents. These provide testament to Ulm’s promotional skills and business acumen.

Searle’s biography does not say much about Ulm’s personal life. Soon after returning to Australia from the Great War, a youthful Ulm met Isabel Winter. They were married in November 1919 and their only son, John, was born in 1921. They soon separated and were divorced in 1927. Rebuilding his life, Ulm lodged in Sydney with a school teacher, Mary Josephine (Jo) Callaghan, who was to become a soulmate and later his second wife. Jo Callaghan was ‘a plain, bespectacled, academic-looking woman, regarded with universal affection’.[3]

Ulm (far left) with Ellen Rogers (centre), Jo Callaghan, and others, New Zealand, 1933 (NLA)

Ulm (far left) with Ellen Rogers (centre), Jo Callaghan, and others, New Zealand, 1933 (NLA)

The third significant woman in Ulm’s life was Ellen Rogers, a young and glamorous secretary who met Ulm in 1928 after the historic Southern Cross flight. Ulm employed Rogers when Ulm and Kingsford Smith established ANA in December 1928 and she continued to work for Ulm until his death. Even after Ulm’s death Rogers worked to preserve his legacy.[4]

This book is an important chronicle of the public Ulm, but there are other aspects of his life that remain to be uncovered. The Australian Dictionary of Biography entry on Kingsford Smith tells us that ‘his contribution to civil aviation was an effort of faith and stamina’. The same could be said of Ulm.

* John Myrtle was principal librarian at the Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra. He has produced Online Gems for Honest History, drawing upon his extensive database of references and including notes about the 1940 Canberra plane crash and the 1937 Stinson crash in Queensland, and has written a number of book reviews for us (use our Search engine). He has also explored the history of the Arthur Norman Smith lectures in journalism.

[1] Ian Mackersey, Smithy: The Life of Sir Charles Kingsford Smith, Little, Brown, Boston, 1998, p. 263.

[2] Eric Campbell, The Rallying Point: My Story of the New Guard, Melbourne University Press, 1965, p. 49.

[3] Mackersey, pp. 90-91.

[4] Ellen Rogers, Faith in Australia: Charles Ulm and Australian Aviation, Book Production Services, Sydney, 1987

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.