‘Half the world away at home’ (review of Connor, Stanley & Yule), Honest History, 15 March 2016

Derek Abbott* reviews The War at Home: The Centenary History of Australia and the Great War Volume 4, by John Connor, Peter Stanley & Peter Yule

With the demise of what Geoffrey Blainey called the ‘Three Cheers School of History’ – ‘ too favourable, too self-congratulatory’ – historians have undertaken a huge amount of research into the real experience of the Great War, not just in the trenches but also on what became known as the home front. The volume under review, a relatively short 230 pages of text (plus an extremely valuable Bibliographic Essay) is a distillation of much of that research, which provides the basis for a nuanced description of Australia’s experience. In putting the book together, the authors have produced a thoughtful and entertaining work, full of illuminating analysis and detail.

The proliferation of war memorials in Australia attests to the emotional impact of the Great War on the Australian community and the need to remember those who had died. These memorials often differ from those in other countries in that they also include the names of those who served but were not killed. The inclusion of the latter names hints at the deep divisions that the war sliced into Australian society. The gulf between those who served and those who stayed home was perhaps the deepest.

The proliferation of war memorials in Australia attests to the emotional impact of the Great War on the Australian community and the need to remember those who had died. These memorials often differ from those in other countries in that they also include the names of those who served but were not killed. The inclusion of the latter names hints at the deep divisions that the war sliced into Australian society. The gulf between those who served and those who stayed home was perhaps the deepest.

However, the war was also to isolate many Australians of German (or merely ‘foreign’) origin; the Labor Party and the community generally split over conscription; sectarian divisions between Protestants and Catholics were deepened and made more toxic; fear of the rising power of Japan exacerbated racial attitudes; the level of industrial unrest in the later years of the war divided the labour movement and hardened the attitudes of much of the wider community to that movement.

The Australia that went to war in 1914 was a work in progress. As former prime minister Paul Keating put it in 2013,

we were moving … to new ideas of ourselves. Notions of equality and fairness – suffrage for women, a universal living wage, support in old age, a sense of inclusive patriotism. And our sense of nation brought new resonances; Australian stories, poetry and ideas of our Australian-ness.

Australia’s economy sank into depression in 1893, contracting by 14 per cent from 1891 to 1895, and recovered extremely slowly thereafter. Immigration stalled (between 1901 and 1905 there was a net outflow of migrants); bank collapses weakened confidence, leading to a net outflow of capital between 1895 and 1910; the Federation Drought from 1895 to 1902 further undermined confidence and slowed recovery.

In the years immediately before the war immigration revived; agriculture, which had diversified under the impact of drought and depression, recovered; manufacturing developed. BHP began construction of the Newcastle steelworks, Sunshine Harvesters were exported throughout the world and, with the freeing of trade between the states and the imposition of protective tariffs by the Commonwealth in 1908, processing of commodities – in woollen mills and butter factories, for example – expanded. The national mood became more optimistic, ‘a world of glorious possibilities’, as Michelle Hetherington described it, opened up, tempered by an acute awareness of the vulnerabilities of Australia economically, politically and climatically.

Sunshine harvester, 1927 (Wikimedia Commons/Bidgee)

Sunshine harvester, 1927 (Wikimedia Commons/Bidgee)

If new ideas of ‘our Australian-ness’ were emerging, they were far from secure. The Great War was to set back the pursuit of those possibilities, in some cases for generations. ‘Notions of equality and fairness’ may have been central to the Australian identity but the treatment of Aborigines, White Australia, the place of women and the strength of the Orange Order suggested that equality was selective and conditional. Under the stress of war suspicion, prejudice and bigotry were to be given free rein. This volume would suggest that the war undermined the nation’s confidence in those ‘glorious possibilities’ and played to its vulnerabilities.

The most immediate impact of the conflict was on trade. The rising cost and declining availability of shipping hit all trade. Australia’s exports of base metals were largely controlled by German cartels and Germany had been an important source of manufactured imports; that trade was shut down. This led to rising unemployment and serious hardship. The economy picked up as alternative markets were found and industries supplying the Army’s needs thrived. In some areas (for example, the processing of base metals) industries were established or expanded which were to remain long-term contributors to the economy. However, mainly because of Australia’s remoteness from the conflict, there was no significant armaments industry and no real boost to the nation’s manufacturing capacity.

Peter Yule, writing on the economy, concludes that ‘[t]he impact of the Great War was overwhelmingly negative and left the Australian economy anaemic and vulnerable’. By confirming the commitment to protectionism, Imperial preference and an economy based on the export of ‘a narrow range of primary products’ the war left Australia tied to an exhausted British economy and at the mercy of a world economy characterised by the overproduction of commodities.

The decline in real incomes between 1914 and 1920 would ‘in peacetime … have been classified as a depression’. After initial support for the war and a period of industrial peace, the labour movement responded to falling real wages and rising prices with growing militancy and radicalisation. Coupled with the conscription referendums this was to split the Australian Labor Party.

The treatment of German Australians and of enemy aliens interned in Australia suggests that Australians at both the individual and official level quickly abandoned ‘cherished traditions of liberty and legality’. The internment camps in which aliens were held were squalid and dehumanising and were recognised as being ‘inferior in practically every respect’ to the conditions of Allied internees in a German camp. The impact of internment, commercial boycotts and wild accusations of disloyalty deeply disturbed the German community.

Sackville Street (later O’Connell Street), Dublin, after Easter Rising 1916 (Wikimedia Commons/Martin & Canfield)

Sackville Street (later O’Connell Street), Dublin, after Easter Rising 1916 (Wikimedia Commons/Martin & Canfield)

The debate over Irish Home Rule in pre-war Australia had indicated the depth of religious prejudice. There is no evidence to suggest that Australian Catholics overall responded to the war any differently from the wider community. However, the response of some members of the Catholic hierarchy to the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin and the conscription referendums in 1916 and 1917 exacerbated the sectarian divide and extended it into every aspect of social life, by linking religion to loyalty and patriotism in the febrile atmosphere of wartime.

The decision to volunteer, or the side one had taken in the conscription debate, became a marker of one’s position in the Australian community throughout the inter-war years. The historian Keith Hancock had two older brothers in the AIF. Turning eighteen in 1916 he did not join up; his family felt that they had done enough. Many years later Hancock told of knocking a couple of years off his age, making him too young to have served, just to avoid the inevitable questions about his war service.

The inferior role of women, despite them having the vote and the huge contribution the largely female voluntary organisations made to the war effort, was confirmed by their wartime experience. There was no great influx of women into the workforce as occurred in Britain; even where women had necessary qualifications as doctors and nurses, for example, the government was loath to employ them. Trade unions were vigilant in minimising the substitution of female workers as men volunteered for military service. Where women were employed they were greeted with a response at once anxious and patronising. Readers of the Grenfell Record and Lachlan District Advertiser were reassured that women boundary riders on Widgiewa Station were ‘wearing a full and ample sufficiency of chest covering’.

The War Precautions Act 1914 armed the Commonwealth with draconian powers to seek out threats to security. Inevitably, those powers were abused, whether by officials accepting unquestioningly accusations of disloyalty directed against those of German descent or by the prime minister himself in directing the police and intelligence services against his political opponents or using the censors to stifle dissemination of the ‘No’ case in the newspapers. There is no evidence of enemy espionage networks in Australia. Despite this the Counter Espionage Bureau and Military Intelligence competed to find subversives, turning on political opponents of the government – the union movement, pacifists, anti-conscriptionists, sympathisers with Sinn Fein, Bolsheviks, the Kuomintang, and even Mormons and Esperanto enthusiasts.

It is easy to mock these excesses but, as Bill Gammage has written, Australia had in 1914 a largely benevolent view of government as a provider of services and regulator of employment. This view was critically undermined by the wartime experience of abuse of authority.

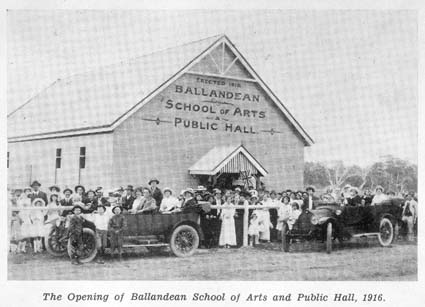

Opening of Ballandean (Qld) School of Arts and Public Hall, 1916 (NAA J2879/3296132)

Opening of Ballandean (Qld) School of Arts and Public Hall, 1916 (NAA J2879/3296132)

John Connor and Peter Stanley, writing on ‘Politics’ and ‘Society’ respectively, trace these deepening rifts. Connor, while acknowledging Hughes’ success in having Australia’s voice heard, concludes that, if Australia became a nation in the war, it was one ‘torn by class rivalry, religious bigotry and the echoing taunts of the conscription campaigns’. Stanley cautions against a wholly negative view of the war’s impact, noting that ‘Australians continued to demonstrate optimism’ and that there is evidence of post-war reconstruction ‘looking to a brighter future’. However, Stanley does quote the judgement of Judith Smart and Tony Wood that the impact of the war was ‘essentially negative, reactionary and destructive of tolerance’.

The Australia that awaited the men of Anzac as they returned home from half a world away was profoundly changed. As they negotiated their way back into a society more bitterly divided than in 1914, and sought security in a fragile economy, it was perhaps inevitable that Anzac would come to represent an ideal of equality and shared burdens, of Australian-ness.

* Derek Abbott is a retired Senate officer with a history degree from Aberdeen University and a long-standing interest in military history. He has reviewed books for Honest History on World War I, and again, Serbia’s Great War and popular resistance in World War II and the future of Asia, as well as two books by John Tognolini.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.