‘War in the long run’, Honest History, 12 May 2015

Derek Abbott* reviews William Philpott’s Attrition: Fighting the First World War

The historiography of World War I is a bitterly contested area: a necessary war to defeat Prussian militarism; a senseless slaughter; blundering donkeys leading heroic lions; sleepwalking politicians; the defence of democracy or capitalists fighting for markets; the new world rescuing old Europe from its folly. A good bookshop will provide your explanation of choice.

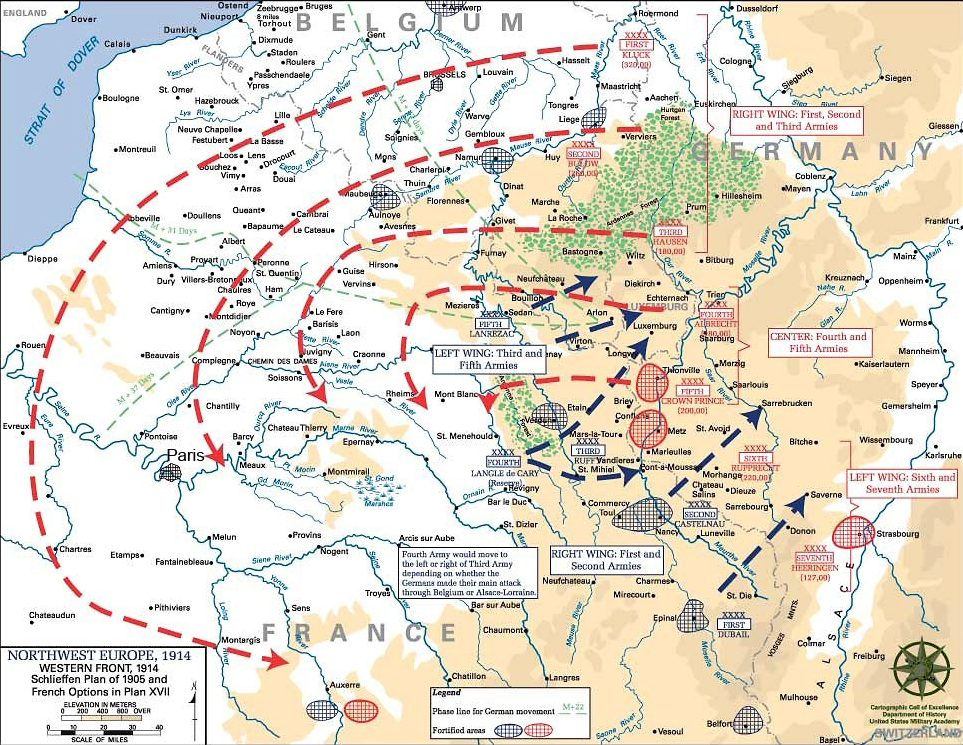

William Philpott’s single volume history of the Great War, Attrition, is a welcome contribution to the realist camp, providing a cool analysis of how the war was fought and why the Allies won. The continental powers all maintained large armed forces and viewed war as an acceptable response to both international and domestic problems; smarter diplomacy in the late summer of 1914 might have delayed, but would not have avoided, war. In the absence of the quick, decisive German victory foreshadowed by the Schlieffen Plan, attrition – the wearing down of the resources of the combatant powers – was the inevitable and necessary means of fighting a war involving modern industrialised powers.

Schlieffen Plan of 1905 and French options (Wikimedia Commons/Soerfm)

Schlieffen Plan of 1905 and French options (Wikimedia Commons/Soerfm)

The war was a process of learning at many levels – military, material, economic, administrative and psychological – as the realities of siege warfare on extended fronts became apparent. The Allies won because they mastered all of these elements (and had the necessary resources) to a greater extent than the Central Powers. This was, says Philpott,

a war of national survival, in which effective mobilization of men, manufacturing and shipping determined success or failure, home fronts sustained armies and navies, mass armies had to be broken in battle and popular will to victory had to be engaged and sustained … (p. 347)

Philpott argues that by about the end of 1915 the Central Powers’ only hope was that the alliance facing them could be broken up and individual countries forced out by heavy defeats – that the French would lose the will to fight after Verdun or the British would be starved by unrestricted submarine warfare. The strategy succeeded to a degree with Russia but too late to achieve a decisive victory and by that stage the United States was engaged and the battles of manpower and material were decisively lost.

The reader is repeatedly brought back to the home front and issues of recruitment, industrial production, access to resources (the advantages of empire and sea power) and home front morale as the determinants of victory. The last, morale, became increasingly important as the war dragged on. President Wilson’s offer to mediate a negotiated peace in early 1917 and later the publication of his Fourteen Points stimulated debate on war aims in all the belligerent countries. The Western Allies’ democratic systems of government were to prove more capable of accommodating and responding to popular disquiet and outright opposition to the war than were the authoritarian and increasingly fragmented systems of their opponents.

The author emphasises the very high casualties the French incurred early in the war – August to November 1914 was arguably the worst period of the war in terms of casualties for the French – so that as early as the beginning of 1915 a manpower crisis was already emerging. This forced the British into a large-scale commitment on the continent which the politicians had, generally, not foreseen and with which they, particularly Lloyd George, were never comfortable.

Carnaby Street, London, shop sign, 1964 (Victorian and Albert Museum/Pat Hartnet) **

Carnaby Street, London, shop sign, 1964 (Victorian and Albert Museum/Pat Hartnet) **

Philpott identifies Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, as being absolutely clear sighted about the nature of the war, its probable course and the level of the commitment Britain would ultimately have to make. ‘[T]he British would have to roll up their sleeves and wade into the mass armies brawling on the continent’ (p. 67). At Dunkirk in November 1914 Kitchener promised Joffre and Foch ‘one million trained English [sic] soldiers by July 1915’ (p. 66).

It is in this context of a growing awareness of the demands that the war was going to make on Britain that her politicians (and some of her military leaders) looked for alternative, second front strategies, including the forcing of the Dardanelles by the Royal Navy. This was a very ‘British’ approach: use the Royal Navy to harry the enemy on the periphery in the hope of achieving disproportionally great results from a limited investment, while leaving the continental powers to slog it out on land.

Kitchener was not enthusiastic about the use of land forces in the Dardanelles; Joffre, the French commander-in-chief, was not consulted on the French commitment because his government anticipated, correctly, that he would oppose it. General Sir Ian Hamilton

was given to understand that the 29th Division [the only regular infantry component of his force] was only on loan and that his operation would always be one of “limited liabilities”, not only to avoid splits in the coalition but also because of the need to contain and then to engage and defeat Germany and Austria … (p. 85)

A dispiriting set of instructions. The campaign rapidly became one of attrition. The Ottoman army, fighting on terrain that favoured defence, had short lines of communication and significant reserves. To overcome these advantages, the Allies were unwilling to commit the numbers, the equipment or the resources, and they lacked the tactical refinement.

As befits a general history Attrition provides brief sketches of the main campaigns of the war, without providing any new insights into the actual conduct of the fighting. It gives due acknowledgement to the contributions of the Allies’ Dominions and colonies, not simply in providing troops but also in the very large numbers of workers recruited (dragooned?) into labour battalions, transport regiments and factories, particularly in France. Is this the first history of the war in which the index contains more page references to ‘women, role in war’ than to ‘Ypres, Battles of’?

The ordinary Australian reader might be bemused, or outraged, to read that the Allied forces (French, British and ANZAC) sent to Gallipoli are characterised as ‘an ad hoc force of largely second rate formations … scraped together’ (p. 85) and that the index contains no entry for Monash or Villers-Bretonneux. Such are the constraints of writing a single volume history.

Joffre inspecting Romanian troops, 1916 (Wikimedia Commons/SFCAR/G Ionescu et al)

Joffre inspecting Romanian troops, 1916 (Wikimedia Commons/SFCAR/G Ionescu et al)

Philpott’s approach, emphasising as it does all the elements that need to be developed and brought together to win a war, is a useful corrective (particularly at this time) to history which emphasises, indeed mythologises, individual soldiers’ stories or makes sweeping, often jingoistic, generalisations about national character. Individual or collective heroism is, of course, well worth recording – and such factors may be important in seizing a trench, winning a skirmish or even a battle – but it is the long-run factors that ultimately win wars.

* Derek Abbott is a retired Senate officer, with a history degree from Aberdeen University. He was a research assistant to Oliver McDonagh and Barry Smith at ANU and has a long-standing interest in military history

** I was Lord Kitchener’s Valet was a London clothing shop of the 1960s, specialising in military-style uniforms. There was also a popular song. The adaptation of the famous recruiting poster indicates how history is turned into myth, then is turned to all sorts of uses. Kitchener was very close to his aide, Captain Oswald Fitzgerald, who went down with him when their ship was torpedoed in 1916.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.