‘Watching the neighbours’ (review of Wesley), Honest History, 13 October 2015

Derek Abbott* reviews Michael Wesley’s Restless Continent: Wealth, Rivalry and Asia’s New Geopolitics

Robert Burns enjoined us to see ourselves as others see us; Michael Wesley would also have us see others, the nations of Asia, as they see themselves and their world. He has produced an ambitious, relatively short but dense book that seeks to provide an informed understanding and more nuanced discussion of this extensive and complex region.

Robert Burns enjoined us to see ourselves as others see us; Michael Wesley would also have us see others, the nations of Asia, as they see themselves and their world. He has produced an ambitious, relatively short but dense book that seeks to provide an informed understanding and more nuanced discussion of this extensive and complex region.

The dramatic growth of Asia has created a new world in which economic power has shifted away from the North Atlantic. The challenges this poses for political allegiances and international legal, economic and trading structures can be seen as an opportunity or a threat to the established order.

Restless Continent invites the reader to consider the continuities in the region’s history, the social and political impacts of rapid development and the legitimate interests of those countries. Manchu emperors, ancient Korean (or is it Chinese?) and Indian Kingdoms, European colonisers, Meiji Restoration, Indian independence, the fall of Saigon and contemporary statistics on economic growth, urbanisation and tertiary education are woven together with regional geography to explore the overlapping sensitivities, pressures and linkages that make up Asia.

Far from being a monolith, Asia is a region deeply riven by old rivalries and conflicts to which rapid economic growth has added new internal and intra-regional stresses. At the same time it is bound together by strong economic and commercial linkages, geographic realities and common interests in maintaining and expanding the conditions that underpinned its economic rise.

The states that comprise modern Asia have largely emerged from the post-colonial era, their boundaries often reflecting ‘lines on maps’ rather than ethnic or cultural divisions; disputed border areas are legion and populations often include ethnic and religious minorities. These minorities – for example, Tamils in Sri Lanka, Moslems in India, ethnic Chinese throughout Asia – have been the target of communal violence or worse. Disputes between Japan, China and Korea over the interpretations of Japan’s colonial rule and of that country’s actions in World War II are well known. Indian independence and partition has left a legacy of nuclear-armed antipathy, disputed frontiers and vulnerable religious minorities in South Asia.

Beneath that relatively recent history there are deeper currents originating in the relationships of the pre-modern era that can surface to disrupt contemporary state-to-state relations. China’s neighbours bridle at any implication of cultural superiority: in 2004 China and the Republic of Korea were embroiled in a dispute over the ‘correct’ description of the ancient Koguryo kingdom (37BCE-688CE); Malaysia and Indonesia dispute the sources of Malay culture; Thailand, which traditionally viewed its neighbours as inferiors, or sources of tribute at best, resents Cambodia’s claims to a uniquely ‘Cambodian’ past; Thailand competes with Vietnam for influence over Laos and Cambodia. Japan, having successfully isolated itself from Chinese influence and resisted European colonialism, adopted some of the colonial powers’ attitudes and came to view its neighbours with a measure of contempt; that these neighbours had succumbed to Europeans during the colonial period was proof of their inferiority.

Internal stability is perhaps the highest priority of most Asian leaders. Economic growth has not removed underlying social tensions and has brought with it new challenges. Memories of the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997 remain fresh – shrinking economies and a sharp rise in poverty scared rulers across the region. Urbanisation not only makes huge demands in developing the necessary infrastructure but also concentrates large numbers of people in cities where the dependence on government is much greater than in rural societies and the failures of government are immediately visible. Cities demand services and infrastructure – food, housing, water, energy, health and education, transport. Their reliability and quality is a visible and immediate test of the capacity of government and, potentially, of its legitimacy.

In reasonably open democratic societies, such as South Korea, Japan or India, failures in these areas, for example the Fukushima nuclear disaster, present immediate political problems but democracy and the opportunity to seek redress also provide a means of managing popular concern. In authoritarian regimes, such as China or Vietnam, such failures present a more fundamental challenge. The internet and the smart phone have greatly reduced the capacity of regimes to control information and suppress dissent. Thirty years ago a disaster, such as the recent Tianjin chemical explosion, could have been covered up, information would have been limited and the response to the incident managed locally. Now such an event is known nationwide and provokes debates about the competence of the government.

Development has achieved remarkable reductions in poverty but also created an expectation of continuing improvement that, if frustrated, can add to social tension. A key factor in the success of the ‘Asian tigers’ has been the investment in tertiary education. In recent years the capacity of societies to provide satisfying and well-remunerated employment has gone into reverse. South Korea is the prime example, with ‘a debilitating skills surplus and problems of underemployment, producing an escalating drag on economic growth and mounting social problems’. More broadly, the failure of once rapidly growing economies to sustain their growth and move to high income status, and the disappointed expectations that this embodies, provides a continuing threat to stability.

The emergence of Asia is already disrupting established international organisations and practice. The developed world wishes the emerging economies of Asia to be ‘good international citizens’, to fit into pre-existing institutional and legal frameworks that regulate trade, finance, migration, even armaments. This is not how regional players necessarily see the world, despite having benefited from some aspects of the existing international order.

When [Asian states] look at today’s world, they see an oligopoly: a set of institutions, properties and understandings designed to preserve the privileges of the western elite that originated them … global institutions and settlements seem to be used regularly to advance the interests of the developed nations.

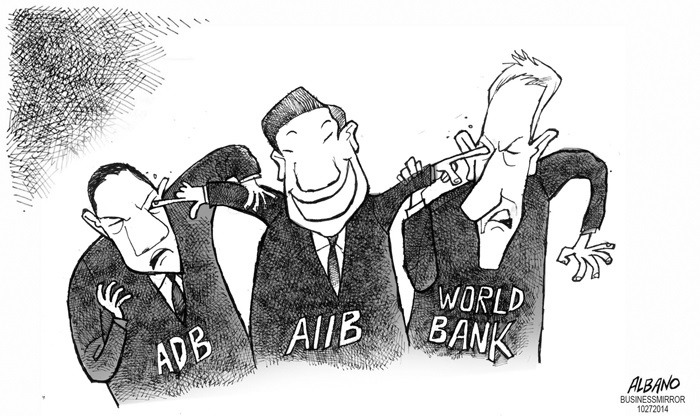

One response has been to create alternative agreements and institutions drawing in participants from beyond the region; for example, the so-called BRICS bank formed by Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa in 2014 was a product of ‘frustration with the lack of reform of the Bretton Woods institutions’ while China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) directly challenges the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank.

Albano cartoon 2014 (Zerohedge/Deusnexus)

Albano cartoon 2014 (Zerohedge/Deusnexus)

There is also an increasing willingness, particularly on the part of the larger and wealthier countries, to be more assertive, most obviously over disputed sea-bed boundaries in the South China Sea, but also to develop military capabilities which can project power along vital trade routes and apply pressure to other countries in the region with which they may be in dispute.

Wesley identifies four ‘overriding preoccupations’ of Asia’s powers. Access to global goods, exploited by the developed nations on their paths to growth but increasingly constrained by environmental and other regulation; respect for nations’ sovereignty; a voice in international institutions which reflects wealth and population, not historical contingency; and assurance, the need for ‘existential security’. As to the future, he puts his money on ‘robust globalism – preferably modified to better reflect non-western preferences’ which would engage the new Asian economies but at the same time protect smaller states from being drawn into spheres of influence of China and India.

As Australia puts the reductionism of three-word slogans and a ‘goodies and baddies’ approach to complex issues behind it, it is to be hoped that Restless Continent finds a wide readership, not only among policy makers but also with a general audience seeking an understanding of this complex continent and the history which shapes it.

* Derek Abbott is a retired Senate officer with a history degree from Aberdeen University and a long-standing interest in military history. He has reviewed books for Honest History on World War I and Serbia’s Great War and popular resistance in World War II.