‘Men alone at the Dardanelles’, Honest History, 24 February 2015

Peter Stanley* reviews episode 3 of Gallipoli (Channel 9), ‘A man alone’. Other episodes reviewed: episode 1; episode 2; episodes 4 and 5; episodes 6 and 7.

Episode 3 of the Endemol-Channel 9 series Gallipoli is entitled ‘A man alone’. I watched it alone; my wife would rather have faced reconciling our cheque stubs than more Gallipoli. Or was I the man alone because the rest of the country was watching the Oscars?

The ‘man alone’ seemed to refer to poor, ineffectual Ian Hamilton, already aware, six weeks into the campaign, that his adversaries are gathering – and he’s not thinking of the Turks. The man alone could surely not be young Tolly Johnson, could it? He’s hardly a man; more the Holden Caulfield of Anzac Cove. His moody adolescent silences (on which the director loves to dwell) are, it turns out, not only prompted by his unrequited jealous desire for his brother’s sweetheart, Celia, but are perhaps founded on more immediate concerns. His understandable apprehensions of mortality are, it seems, fuelled by a visit to a fortune-teller in (presumably) Cairo. (You can find bare-breasted, belly-dancing French women with a snake pretty much anywhere in Ashfield or Newtown or from wherever Tolly hails in Sydney today: thus has Australia changed since 1914.)

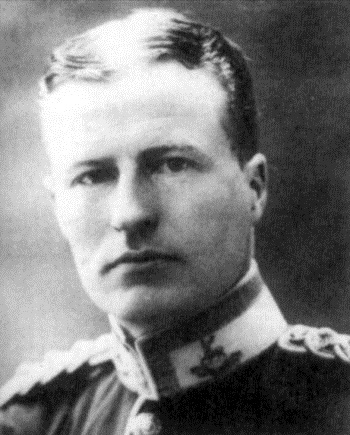

Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett (Wikimedia Commons)

Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett (Wikimedia Commons)

That all of the quartet of Tolly, his older brother Bevan, their irritating larrikin mate Cliff and the bespectacled Dave have survived unscathed so far – five or more weeks into the campaign – is at the very least surprising. Statistically, one of them will die on Gallipoli, two will be wounded and the survivor be evacuated sick. We’ll have to see if their odds decrease as the episodes pass but locating the action in episodes 2 and 3 at Quinn’s Post should have shortened them. Christopher Lee’s advisors at the War Memorial must have told him how deadly Quinn’s was and our heroes have been at Quinn’s for several weeks. It was reputed to be the most dangerous place in the Anzac line.

Presumably, Lee needed to keep the quartet together, perhaps to establish them as characters, regardless of their historical likelihood of survival. The scenes of Cliff, with casual bravado, bowling fizzing bombs into Turkish trenches a few metres away rings hollow. Quinn’s was a place of trauma, where men came out of a shift in the foremost trenches declaring that they would endure a season in hell rather than another hour there. Cliff still thinks it’s all a lark. (Again, his mates are still standing firing over the parapet; at Quinn’s that would have been suicide.)

The pivotal action in episode 3 is that the brooding, tongue-tied Tolly (now a lance-corporal, oddly promoted over the heads of older, more assured men) and his mates are selected to make a night attack on Dead Man’s Ridge, fifty or a hundred yards to the north. Attacks and raids were made from Quinn’s – a couple by Australians (mostly the despised Light Horsemen, who in this Gallipoli are the butt of increasingly tedious jibes) and by New Zealanders, though in this version of Anzac the ‘NZ’ seems silent. (In this, a major Australian production has once again chosen to deliberately slight our closest neighbour and supposed partner in the sacred enterprise of Anzac. Perhaps the lack of a pre-release deal with a New Zealand network sacrificed the historic relationship. So much for telling the story straight.)

Anyway, Tolly and his mates are depicted creeping along a wash-way, accompanied by the clink-clank noise that we now know is added by the Foley artists and not an actual sound; here it’s loud enough to wake a dozing Turkish sentry. Exactly on what historical prototype this scene is based is an open question. It was literally impossible to leave the front line at Quinn’s in any more than ones or twos without calling forth a storm of bombs and rifle and machine-gun fire. In reality, Dead Man’s Ridge could not be reached on foot from Quinn’s without the attackers clambering down and up a corpse-strewn gully and attracting a storm of fire in the process. But Tolly’s mob seem to be able to sally out at will along a convenient ditch. The point of the scene seems only to have been to get Tolly wounded but there would have been several more convincing options available to the writer. (Oddly, the wound Tolly seems to have suffered is a puncture wound, not a gunshot wound. This has all been too little thought out, and in the writing, not so much in the execution.)

Let’s digress here and think for a minute of the officers in Endemol’s Gallipoli. (I mean the junior officers; we’ll get back to the generals presently.) Writer Christopher Lee’s script seems to have only one species of officer: captains. One of the words I have not written on my pad is ‘lieutenant’. This is curious, because the grade of officer most soldiers would have encountered routinely was that of the junior officers who commanded their platoons. In the Endemol Gallipoli lieutenants apparently do not exist. (To digress from a digression, in other times, in every Great War artistic iteration from Journey’s End to The Blue Max to the mini-series Anzacs, key characters were junior officers; this Gallipoli is unusual in ignoring what the army calls subalterns.)

Why have lieutenants been left out? Could it be that the producers wanted a clear distance (they probably called it a ‘space’) between the men (who they probably called ‘the enlisted men’, American-style) and the officers, so captains became the default officer; besides Sergeant Perceval the tubby unnamed captain represents authority within the unit. Or did they think that the word ‘lieutenant’ – pronounced in the AIF ‘lef’tenant’ rather than the US-style ‘lootenant’ – was too hard for lay audiences to grasp? What’s going on here? The International Movie Data Base tells me that there are at least three lieutenants introduced in subsequent episodes, so perhaps they are keeping lieutenants and captains distinct so the lay audience can tell them apart? Who knows?

General Sir Ian Hamilton, c. 1910 (Flickr Commons/Library of Congress/Bain)

General Sir Ian Hamilton, c. 1910 (Flickr Commons/Library of Congress/Bain)

That digression on lieutenants was prompted because in all the actual raids launched from Quinn’s the leaders were lieutenants, most of whom died in the attempt. In Endemol’s Gallipoli an attack on Dead Man’s Ridge is led by a 17-year-old newly minted lance-corporal. What on earth were they trying to do? If the scene was supposed to emphasise the amateurism with which the half-trained AIF took to battle it succeeded. Other than that I can’t think why it was included. But at the end of it Tolly falls with a puncture wound to the chest and the next episode seems to be set in Luna Park hospital, Cairo, aka the superbly versatile Royal Exhibition Building, Melbourne.

Gallipoli the series seems to me to be losing its way. In Carlyon’s grand narrative of the campaign (which fed off the drama of tragedy and failure) nothing much happens between the 24 May truce and the August offensive (hence the focus on journalist Ashmead-Bartlett’s shenanigans in this episode). The series feels, too, as if it’s bridging more significant surrounding episodes, having opened with the confusion of the landing and the drama of the 19 May attack and the truce. Tolly’s wounding will take us to Egypt, presumably killing a month or two before the narrative returns to the peninsula.

I have a suspicion that seven episodes is too many to sustain this arc; viewing figures for episode 3 are down another ten per cent. The series is supposedly being hailed by critics – it’s leaving them ‘breathless’ according to Endemol’s Facebook site, though the critic they quote, from the Australian Women’s Weekly (‘bold, stark and honest’), is hardly Cinema Papers or Australian Historical Studies. On the other hand, Channel 9 needs a popular audience, and one that sticks with it to the end. And we all know how it’s going to end, don’t we?

* Professor Peter Stanley of UNSW Canberra is President of Honest History.

Morning Peter, thankyou for your reply to my question about mules in the comments on episode 1.

I’m grateful to be able to learn more on not only Gallipoli but the complete WW1 subject, and as you have helped me in the past I hope you don’t mind me asking questions. You may recall I first asked questions after reading your book “Bad Characters” some time ago, after I had found out my grandfather was charged and found guilty of desertion, though he had been in British Red Cross facilities, CCS, hospital and rehabilitation, following a German gas attack in 1918.

The education has cemented my beliefs that the history does not require an adulterated, probably profit driven, fantastic interpretation of what was basically one of the greatest debacles in world events. The more I read, and the more I speak to people, the more I am convinced everyone has a story. I will look forward to reading your book on the Indian Army, I feel sure it will further consolidate my ongoing education. All the best, thanks for the opportunity. Robert.

Peter, you are entertaining me with your analysis and verbiage, but as with my unanswered questions relative to episode 1, I must ask, have you sighted any donkeys yet, and as an exserviceperson, I don’t mean the denigrated Sirs? Robert.