‘Settling in for the long haul at Gallipoli’, Honest History, 22 February 2015

Peter Stanley* reviews episode 2 of Gallipoli (Channel 9), ‘My friend, the enemy’. Episode 1 reviewed. Episode 3. Episodes 4 and 5. Episodes 6 and 7.

The big Turkish attack of 19 May and the resultant truce of 24 May animate the drama of episode 2 of Endemol-Channel 9’s Gallipoli. Well, I say animate, but it all seems rather lacklustre, to be honest. Despite the magnitude and span of the book that inspired the series, Les Carlyon’s Gallipoli, Endemol’s version seems rather cramped. The first word I wrote on my pad while viewing was ‘unconvincing’. The trenches are travesties, the noises are muted, the details continually seem wrong; the horror, for all that the production’s ‘Prosthesis’ and ‘Bodies’ teams have tried, seems less convincing than the reality that I’ve imagined from photographs and documents. I don’t say that the producers haven’t tried; but I have to say that it isn’t working for me.

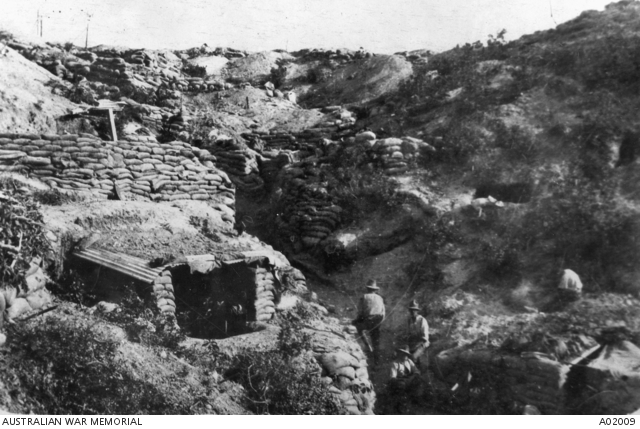

Quinn’s Post, c. May 1915 (Australian War Memorial A02009)

Quinn’s Post, c. May 1915 (Australian War Memorial A02009)

The fictional battalion to which the little gang of four who carry the burden of the drama belong is now holding Quinn’s Post. Now, I know a bit about Quinn’s Post because I wrote a book about it: Quinn’s Post, Anzac, Gallipoli, published in 2005. In the way of the book trade these days it may as well never have existed. You can buy a digital version of it, but it’s literally out of print and public libraries tend to chuck out anything more than five years old.

Anyway, Gallipoli’s Quinn’s is different to the Quinn’s I imagined from the records I consulted. In the first month or so of the campaign, Quinn’s was a chaotic place of front-line trenches too shallow for safety (the Australians holding them could not be compelled to dig them deep enough and they paid for that laziness by suffering casualties from snipers). In Endemol’s Gallipoli men seem to stick their heads over the parapet at will but suffer no consequences. In reality, the volume of bullets and bombs coming over the Australian parapets there compelled men, trying to retaliate, to lob jam-tin bombs virtually at random and to fire rifles by holding them up over the sandbags and firing blind.

The racket at Quinn’s hardly ever ceased but in Endemol’s Gallipoli they all seem to knock off at dusk so the characters can have chats that edge the plot along. No one seems to be especially exhausted or frightened though Dave Klein’s admission that he knowingly kills his first man on 19 May (three weeks into the campaign) at least hints at the varying reactions to the demand that soldiers kill easily and often. This is a truth, well presented.

Most disappointing, though, is the production’s failure to evoke the intensity and terror of the great Turkish attack of 19 May, when waves of Ottoman troops came on, in close-packed ranks at a seemingly unstoppable jog-trot, chanting ‘Ul-lah! Ul-lah! Ul-lah! – something a Turkish soldier alludes to in talking to Tolly during the 24 May truce. Not only do the Turkish attackers in the program not chant terrifyingly like this but there aren’t nearly enough of them – and they actually weren’t stopped by rifle fire from the infantry holding Quinn’s but by machine-guns on the flanks, scything them down in great heaps until even the Turks’ resolve gave way and the survivors refused to attack again. I know it can’t be easy to find extras who look like Ottoman soldiers in rural Victoria but, if you want to convince us, you’ll have to try harder. As I say: not the Quinn’s I wrote about.

General Birdwood swimming at Anzac Cove, May 1915 (Australian War Memorial G00401)

General Birdwood swimming at Anzac Cove, May 1915 (Australian War Memorial G00401)

In my review of episode 1 I expressed relief that at least we hadn’t seen any Hollywood heroism. Sadly, that wasn’t long coming. In episode 2 there is a ludicrous scene in which the sergeant organises his men to silence what I gather the producers think of as an Ottoman ‘machine-gun nest’. Bevan (the elder brother) volunteers to storm it – alone – while his comrades give what the sergeant calls ‘covering fire’. In doing this deed, Bevan slips and twists his ankle so the 17-year-old Tolly races out, kills the crew and disables the gun. Such an act would have merited at least a Distinguished Conduct Medal – I know because I nearly wrote a book about DCMs on Gallipoli once – but in fact the entire scene is simply incredible, in the literal meaning of that much abused word.

To sum up, no-one emerging from Quinn’s could have lived for a more than few seconds and there were no machine-guns in what the Anzacs called Turkish Quinn’s – like their enemies’ guns they were located on the flanks. The little scene is, of course, supposed to further the brothers-in-war plot that has so far failed to ignite but surely Christopher Lee could have found something more credible?

I am beginning to feel increasing sympathy for the series historical adviser, Dr Dayton McCarthy, who must be realising that he will be held responsible for aspects on which he was neither consulted nor perhaps listened to. I have the feeling that, if he did appear on location, he must have found many details already beyond correction, such as the way brand-new sandbags appear to have been plonked on top of trench edges plainly dug by JCBs. Other details, such as men smoking filter-tipped cigarettes, may have escaped him.

I have the feeling that the producers may not have welcomed too much ‘advice’, even when they could have used it. This is not to say that the series does not at times convince by its look – the trench-sides are realistically smeared with blood (from bomb-wounds) but too often the production team have given us an impression of what they imagine Gallipoli looked like rather than what it was like. I think Dayton McCarthy ought to be commended for the amount he got them to get right rather than merely be wigged for the remaining mistakes. And Dr McCarthy was working essentially alone. ‘Additional research’ for the series was undertaken, the credits inform us, by Rachael Turk, who, it turns out, is a superbly qualified drama producer but who has no relevant historical knowledge or experience.

The series theme (as the Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett character said in this episode) that ‘our commanders are very little men’ continues, of course. In episode 2 the generals are shown to be remote from the reality on the peninsula, even when they visit the trenches (in uniforms that look straight from the dry-cleaners). The generals are moral pygmies in Carlyon’s universe. Except that in the case of Birdwood, who ought literally to be a little man, he is played by the six-foot-plus Anthony Phelan as a beefy chap.

The generals’ indictment in this episode is to be reluctant to countenance the idea of a cease-fire (actually suggested by the Turks, not a front-line Australian officer). Walter Braithwaite (played splendidly as a stage villain by Nicholas Hope, contemptuous of the supposedly doddering Hamilton) represents senior officers’ reservations, though Anzac sector commanders such as John Monash, who was responsible for Quinn’s, also deprecated the idea of a truce. Paradoxically, except that the corpses should be stiffer, more bloated, black and maggot-blown, the depiction of the 24 May truce is quite well done, albeit with too few flies, which are cheaper than extras but harder to direct.

Mustafa Kemal inspects Turkish perimeter defences, Gallipoli, 1915 (Australian War Memorial A05288)

Mustafa Kemal inspects Turkish perimeter defences, Gallipoli, 1915 (Australian War Memorial A05288)

A curiosity of this Gallipoli is that Charles Bean is so absent. He has had two appearances, each of a line in the first two episodes, but if the International Movie Data Base is correct, that’s all we’ll see of him. This, too, is in accord with Carlyon’s prototype. Carlyon disparaged Bean as a writer and as a mere counter-of-bullets (and he did count them – it’s how we know how heavy and constant the fighting at Quinn’s was) while shamelessly quoting and paraphrasing him: a back-handed compliment if ever there was. The TV-mini-series version of Carlyon’s book – which this series is – naturally also diminishes Bean’s part in the story. This could be salutary – as well as recording the Australian experience of Gallipoli, Bean could not help writing himself into it, and not necessarily productively – but it seems in this case that Christopher Lee may have adhered too slavishly to Carlyon’s text, in the process perhaps throwing out the baby with the bathwater. Either way, this is the last we’ll see of Charles Bean, meaning that we will never learn why he was depicted in civilian clothes when he actually wore an officer’s uniform minus rank badges.

Gallipoli’s viewing figures seem to be declining, with viewers falling off even more rapidly than those who abandoned Carlyon’s wordy tome half-way. Episode 3’s trailer suggest that the inevitable nurse is to make an appearance, as in last year’s mini-series Anzac Girls unfeasibly younger and more attractive than her historical prototype.

* Peter Stanley of UNSW Canberra is President of Honest History. Among the 27 books written by Professor Stanley are several on Gallipoli, including Quinn’s Post, Anzac, Gallipoli (Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2005)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.