Diane Bell*

‘Miles Franklin and the Serbs still matter: a review essay’, Honest History, 1 December 2015

[Publication details of the work reviewed: Vladiv-Glover, Slobodanka. (Editor). (2014). ‘Writings from the Balkan Theatre of War by Miles Franklin (Extracted from the Archives of the Mitchell Library)’, Transcultural Studies: A series in interdisciplinary research, Special Issue, ‘The Serbs and Miles Franklin in World War 1 in documents, fiction and commentary, Vol. 10, No. 2: 1-108.]

These comments of a camp cook upon experiences gained as a voluntary member of the army of the British Red Cross are submitted unpretentiously for what they are worth as a document of the war.

Thus begins Stella Miles Franklin’s remarkable Nemari Ništa (It Matters Nothing): Six Months with the Serbs (p. 1).[1] . Franklin is writing of the period July 1917 to February 1918. Bulgarian and Austro-German forces had advanced into Serbia. The allied forces and the Serbian army were pushing back. Readers familiar with the shifting fortunes of the Serbs during World War I to the present will be interested in Franklin’s encounters with the various nationalities and her observations on their attitudes to religion, territory, women, character, class and manners.

Miles Franklin at the Scottish Women’s Hospital Camp, Ostrovo, c. 1917 (Looking for the Evidence/Jennifer Baker)

Miles Franklin at the Scottish Women’s Hospital Camp, Ostrovo, c. 1917 (Looking for the Evidence/Jennifer Baker)

Writer, feminist, nurse, housemaid, cook, journalist, secretary, workers’ rights advocate, supporter of the arts in Australia, Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin’s (1879-1954) contribution to the Australian literary canon is profound: My Brilliant Career, All That Swagger, My Career Goes Bung, On Dearborn Street, Some Everyday Folk and Dawn. Her influence in shaping Australian writing lives on in the annual Literary Award, established in 1967 through her Will, and the more recent major literary Stella Prize that specifically celebrates and encourages women’s writing. And now, from the archives of the Mitchell Library, Sydney, we have in print Franklin’s Six Months with the Serbs plus a four-act play of the Balkan Front Today, which is similarly based on characters from this sojourn. These are manuscripts that repay careful reading, require contextualisation and raise several critical questions.

Why was Franklin working in a hospital in Macedonia during World War I? She had been working in the United States since 1906. Her brilliant career was going bust. Her biographer Jill Roe writes:

Declaration of World War I in Europe clarified some things for Franklin: she finally rejected marriage, which she considered ‘rabbit’ work and, unnerved by American chauvinism, she reasserted her nationality. Faced by mounting ideological or personal conflict within the league [National Women’s Trade Union League of America], she took three months leave and sailed for England on 30 October 1915, vaguely envisaging war-work.[2]

From there Franklin endured several less than satisfying jobs and published a number of pieces in the Sydney Morning Herald but her finances were strained. In June 1917 she accepted the role of cook as a voluntary worker for the Scottish Women’s Hospitals at Ostrovo, Macedonia, and with keen eye for detail began her documentation of World War I.

As an anthropologist I found Franklin’s approach compelling. She is doing a kind of participant-observation fieldwork and she is interested in comparative materials. She is in tune with the rhyme and rhythm of the people and place and she is reflexive. Her egalitarian self rebels against the classism of the British officers while the image of the Serb as ‘noble savage’ enhances their eugenic standing. Her feminist self lampoons foolish male pride while her feminine self delights in male chivalry. Her belief in education as fundamental to postwar peace is set against her analysis of the privilege offered by a Cambridge or Oxford pedigree.

Franklin’s prose charms and beguiles the reader. Australian imagery and sensibilities pervade her sketches: ‘I inwardly chortled like a kookaburra’ (p. 4); on boarding the boat for France ‘for all the world like sheep in a shearing shed awaiting sorting for the great yearly upheaval’ (p. 5); of the lull in the war they were ‘like a billabong left by a receding flood’ (p. 28); on being bitten in the mouth after swallowing a wasp, she felt like a ‘poisoned dingo’ (p. 48). Her humour is delicious: the Serbian custom of kissing is compared to an ‘Anglo-Saxon man who would rather face a cannon than a kiss from one of his own sex, though cases of isolated bravery are on record’ (p. 75).

Franklin in the field

So, to begin with the content and Franklin’s modest opening words that she is offering the document ‘for what it’s worth’, to which I’d respond, ‘A great deal’, and not only as a document of World War I.

Franklin takes us on her journey into the field. We travel with her from London through France and Italy to the ‘American Unit’ (so named in honour of its US donors) of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals at Ostrovo, Northern Macedonia. The stories of lost luggage and humourless bureaucrats resonate. We share her excitement, curiosity and apprehension. In 12 astute sketches, we are introduced to the characters, complexities and calamities of life in this 200-bed tent hospital. Franklin ranges widely: she depicts the drone of not too distant big guns as a ‘pleasing orchestra’ less deafening than those endured in Chicago or New York (p. 28); explores the culturally diverse neighbouring hamlets in the Macedonian countryside; enjoys days and nights out with various local and visiting characters; calibrates the seasons against the changing hues of Mt Kaimacktchalan; suffers the oppressive heat of summer and winter ills such as chilblains; and becomes a victim of the all too prevalent mosquito-borne malaria.

Five members of the Scottish Women’s Hospital unit (Looking for the Evidence/Jennifer Baker)

Five members of the Scottish Women’s Hospital unit (Looking for the Evidence/Jennifer Baker)

Sketch 1: Our camp

Franklin’s evocative description of the hospital camp is of a hive of activity: hard physical labour like carrying water; a mere day a month free, plus a half day a week and three to four hours rest on most days; appalling summer conditions with flies, lack of shade, and 115 Fahrenheit in the poorly located ‘cook-shack’. But, as Franklin notes with her inimitable wry humour, ‘a matter of climate is of little import to an Empire saver’ (p. 19).

Sketch 2: Recreation

The kitchen where Franklin toils is a ‘flourishing social centre’, a cuppa always at the ready regardless of rank, religion or region. In their free time the sestra (nurses or sisters) swim in Lake Ostrovo and might be glimpsed ‘dancing a spirited reel on the shores in their bathing tights’ (p. 24). Of her language learning, she writes, ‘The Serbian women must be great to produce such sensitive affectionate men’ (p. 27) as teachers.

Sketch 3: The plight of the Serb

The weary Serbs, who had been part of the retreat from Serbia, remind Franklin that there had been during that earlier period a lull such as she is enjoying. Many Serbs pine for their homeland. Depression, frustration and resignation shape their lives. Franklin appreciates that, unlike the men there for the duration, her service is limited. She can leave. She notes the pragmatism marking the futility of war for the Serbs, who are discharged only to return to the front, in their quip: ‘Nemari ništa (Nothing matters). I have been here a long time, it is well that I go to the front now and others have my place’ (p. 29).

Sketch 4: Camp characters

Franklin’s pen portraits of her co-workers, patients, visitors and neighbours show her at her astute and affectionate best: of the Matron she writes, ‘not a button, nor a string, a thermometer, nor a tongue depressor in that hospital escaped her observation’ (p. 32); of Guya, the natural genius with machinery, she says he is equally capable of mending fine jewellery, a Primus stove, or rebuilding a new car from old (pp. 33-4); of Urosh Ružitchić, a young multi-lingual Bosnian medical student, she notes he has little time for his fellow educated Serbs, who in his view promise but do not deliver (p. 40).

Sketch 5: Malaria

By late summer, malaria became endemic with as many of a quarter of the staff down at any given time. Malaria recurs, complicates recovery from other conditions, is treated with painful quinine injections, and accompanied by hair loss. Franklin eventually succumbs and even her stoicism is tested by the injection that renders her partially disabled for three months such that she sews standing up (pp. 49-50).

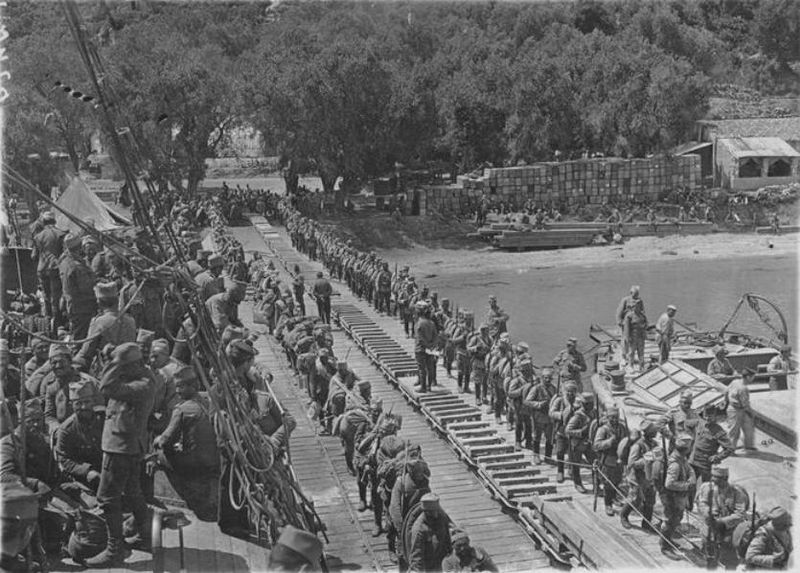

Serb soldiers boarding French ships for Salonika, Spring 1916 (Wikimedia Commons/Chemins de memoires)

Serb soldiers boarding French ships for Salonika, Spring 1916 (Wikimedia Commons/Chemins de memoires)

Sketch 6: Our highway of chance villages – Vodena-Voz

Franklin depicts the huddled unkempt villages living in fear of the comitadji[3] where ‘pathetically weather beaten’ Balkan women engage in the communal labour of winnowing and washing. ‘The sanitary conditions are described in Leviticus’, writes Franklin as she notes, ‘I loathe primitiveness that has no redeeming features’ (p. 52) and reflects that these local conditions are context for the exploitation of like peoples in the US and Canada.

One striking feature of all Franklin’s sketches is the cultural diversity of the people with whom she comes into contact in the surrounding Macedonian villages. There are the Turkish populations, with reports of massacres of Christians in their precinct five years ago, and the veiling of women that contrasts with the entirely different headdresses of the ‘Roumanian’ (p. 52). Franklin details the poultry, the sacred sweet basil, and mud oven doors sealed with dung (p. 53). She and her companions fear nothing as they roam through the villages, secure in the knowledge that their ‘big brothers, protective, chivalrous’ Serb soldiers, are omnipresent.

Franklin extols the virtues of Serbian manhood from their physique, dignified bearing, exquisite teeth, blue eyes, fair skin tanned by sun, dark hair, and absence of ‘bulge at back of head’ as with the British (pp. 21-2). She contrasts Serbian civility with British snobbery: if a British officer is on board, the sisters would not be offered a lift whereas the Serbs would turn around in order to accommodate the Englesky (English) sisters with an accommodating Nemari ništa (It matters nothing) (p. 56-8).

On half days spent in Vodena (Edessa) the sisters mingle with Greeks, Turks, and ‘refugee gypsies’ (p. 62) and enjoy the voz (train) where they might find themselves riding with pigs or explosives; where kindly Serbian soldiers take the nails from their boots to fasten blankets to shield the sisters from chill winds and hold a lighted candle to illuminate their way (p. 65); and where Russians and Serbs sing in harmony, while Annamites (French Chinese) hit high notes.

Sketch 7: Society, hospitality

Franklin writes of the Senegalese and Arab road builders (‘French subjects’ she notes) with their twice daily prayers (p. 69); the daily movement of flocks, herds and ox carts; and armies that ‘streamed back and forth’ (p. 69): ‘Men and mules forever’, summarises Franklin (p. 70). She playfully dubs the French who speak only French as ‘continentular’ (continental+insular, p. 72). What is it all for? asks Franklin. Perhaps the ‘strategists and spies knew. We did not, and could not. So we dropped into the Balkan trance wherein we did our appointed work, took our pleasures and ceased to fret’ (p. 71).

Sketch 8: Femininity, at the front

‘To the Serbs we were all Sestre [sister, nurse]’, declares Franklin who revelled in the sisterhood of company of the camp (p. 84) and took a relativist stance on the ‘suffocating headdresses’, ‘frightful clothes and limited lives’ of Macedonian women on whom they gazed ‘pityingly’ while recognising that the returned stare was one of derision for Franklin and her cohort ‘lost alike to God and man’ (p. 86). The curious mixture of cultural relativism, ‘noble savage’ romanticism, and eugenics that underpins this sketch cries out for close reading by scholars of Franklin’s oeuvre, early 20th century social philosophy, and feminist theorising.

Sketch 9: Music in Macedonia

Franklin, who had dreamed of a singing career[4] is attuned to ‘the most soporific of lullabies’ in the guns that roar like a cataract; delights in the bugles, the brook-like goat and cow bells in the background; cherishes the reed flutes, mandolins, a real piper, and local concerts; and concludes that the gramophone is as necessary to convalescents as a physician (pp. 88-92).

Sketch 10: In the order of the day

Franklin measures seasonal changes against the mountains. In autumn, ‘Kaimacktchalan wrapped himself in clouds for days at a stretch and mist and drizzle shut the nearer landscape from us’ (p. 94). In winter, ‘mountains clear cut on a rose and pink which deepened to wonderful blues as the sun came up clear and splendid in a cloudless sky’ (p. 98). Franklin chronicles the daily routine. She writes graphically of her bout of malaria; longingly of hot baths; proudly of the improvisations and economies for keeping warm in unrelenting cold and wet. Franklin captures the drama with, ‘Hot water bottles froze if they got to the edge of the stretchers’ [i.e. sleeping frames] but the Serbs ‘stripped to the buff washing outside their tents’ (p. 98).

St Elijah chapel, Kaimacktchalan, commemorating Serb soldiers killed in battle, 1916 (Wikipedia)

St Elijah chapel, Kaimacktchalan, commemorating Serb soldiers killed in battle, 1916 (Wikipedia)

Sketch 11: The position of the Serb

This sketch might be renamed ‘In praise of Serbs’. Franklin enumerates their virtues: the security they provided against attacks by ‘Bulgars and wolves’ (p. 100); the wisdom of a young Serbian officer unselfconsciously presenting a lecture in his fractured English, ‘While the British subject is distinguished by an over-devil-opp-ed conscience, the Serb has preserved his soul’ (p. 100). Perhaps, Franklin muses, ‘if the Serb and the British could get together, and the Serb modify his soul by a little of British conscience, and the British learn from the Serb not to be so surreptitious about his soul, something would have been gained’ (p. 100).

However, Franklin is quick to add the caveat that it would be ‘daringly ridiculous’ to generalise on the basis of limited knowledge gleaned from ‘exiled remnant war-weary, dispirited men, wrecked by malaria and phthisis [TB] and cut off from their normal surroundings’ (p. 101). ‘Our best are dead, you can have no idea of the real Serb’ was the opinion of thinking Serbs whom Franklin met. In her view, through the torture of five years fighting, the Serbs had held onto their ‘clean self-respect, their national pride, their spiritual sensitiveness, their simple honesty, their tender affectionateness. Such a people may be exterminated but never conquered’ (p. 101).

Franklin casts herself as sharing their primitive and unlettered character and depicts worldliness as a taint, the ‘progress of modern machinery’ as the genesis of inequality. Her vision is for Serbians to ‘evolve in their own way free from dictation’ (p. 104). Schools of snobbery she casts as divisive. ‘Relatives can get along much more comfortably with different religions than with a different manner of drinking soup,’ Franklin contends (p. 105).

Franklin writes approvingly of the school of dentistry and school for refugee children in Vodena as the ‘bravest nucleus of educational enterprise’ (p. 105). In her vision there would be mobile schools that could return home with the children; the well-educated young men of Cambridge, Edinburgh and Paris could teach without alienating their students. Similarly, great hospitals could train nurses.

In many ways Franklin’s Serb is the noble savage: simple, primitive reared in far solitude (p. 103). In other ways Serbia, the little, happy, self-sufficient country, could be the new Europe, freed of the chains of old Europe. Franklin’s biographer Jill Roe discerns the ‘glimmering of a new ethical position’ that Franklin sought in leaving the US: ‘From old empires, new nations might arise’.[5]

Sketch 12: S bogom! (Goodbye)

‘When again?’ asks Franklin, would her comrades all live through such times, with such company and genuine affection. In her farewell roll call of the names of her mates, the last is to ‘Franky Doodle’. This is the name under which she enlisted and no doubt yet another example of Franklin’s playfulness with names. We have ‘Frankie’ from Franklin and ‘Doodle’ to evoke Yankee Doodle who, in the words of one of the versions of the rhyme, ‘went to London just to ride the ponies.’ Franklin had left ‘Yankee-land’ for London before she rode off to war service.[6]

From manuscript to publication

In the Preface to this Special Edition of Transcultural Studies, the Series Editor, Slobodanka Vladiv-Glover, dedicates the publication to Stella Miles Franklin and her literary testimony to the Serbian soldiers in World War I (p. iii) and relates how the publication came about (p. iv).

The present publication project was triggered by an inquiry to me from a colleague who is an American Slavic Scholar and cultural historian, who asked whether I could check the Mitchell Library for material on Stella Miles Franklin and her war-time involvement with the Serbs. I passed on her request to my Sydney friend and colleague, Ms Mirjana Djukić (BA Hons, Belgrade University, Grad Dip LIS UTS Sydney). After some delays, the relevant manuscripts were found and scanned, by which time there was a new development. The Serbian Ambassador to Australia, HE Mr Miroljub Petrović, requested my collaboration on the organisation of an event at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra in October 2014 to commemorate 100 Years of World War One by highlighting relations of the Serbian Army and Australian volunteers in the Balkans. The name of Stella Miles Franklin came up. From there to the realisation of the publication of her war-time novel and drama was just a matter of intense editorial work. Credit must go to my two collaborators: Mirjana Djukić, for extracting the manuscripts from the Mitchell Collection, ordering them and scanning them, and to Ms Jenela Bogdanović (BA Monash University) for typing the multilingual (English, Serbian and French) manuscripts into word documents.

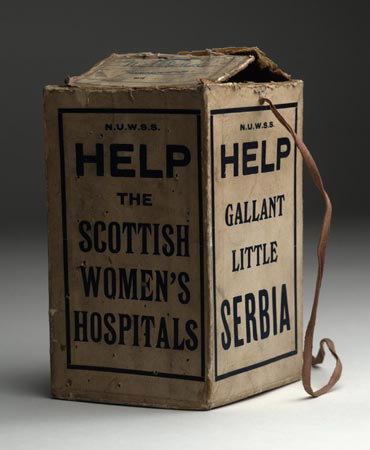

Collection box for Scottish Women’s Hospitals (Looking for the Evidence/Jennifer Baker)

Collection box for Scottish Women’s Hospitals (Looking for the Evidence/Jennifer Baker)

I am delighted that Franklin’s accounts are now in the public domain but have some nagging concerns regarding their route from the Mitchell Library to the journal of Transcultural Studies. There is fine detail in the above paragraph but no call number for the manuscript is cited in the journal. After tooling around on Trove, I found two possible locations for a manuscript which appeared to match the one described as ‘Extracted from the Archives of the Mitchell Library’ in the ‘Table of Contents’ (p. i). Firstly: ‘Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW Location: MLMSS 6035/1-19: The title translates as ‘It Matters Nothing’. The manuscript contains corrections and additions. Each copy is signed ‘Miles Franklin Outlander’, and is illustrated by a different set of photographs. (This manuscript gives an account of her nursing experiences in Serbia during World War I.)’[7] Secondly: ‘Miles Franklin papers, mainly literary manuscripts, [1900-1954?] Microfilm – CY 766, frames 411-635 (MLMSS 445/4: ‘Ne Mari Nishta, it matters nothing’)’.[8] Which of the copies of ‘It matters nothing’ was ‘extracted’? Were any of the photographs ‘scanned’? I cannot tell from the publication.

Vladiv-Glover states that this ‘first time ever publication’ of the sketches and the play are being ‘published simultaneously in Australia and the USA by the Slavic publisher Charles Schlacks (Idyllwild, CA) and Plenum Online Publishing (Australia), with the kind permission of the Mitchell Librarian, State Library of NSW’ (p. iv). For what was permission granted by the Mitchell Library? Scanning, copying, extracting and editing are noted, but what of copyright? No further details regarding the status of the manuscript are offered in the ‘Preface’ or on the Imprint Page where Copyright appears as ‘2014 Charles Schlacks Jr, Publisher’. I remain curious regarding the conditions of reproduction of an unpublished manuscript. The Mitchell Library has confirmed what my online search had indicated: the materials were within the collection of Miles Franklin’s unpublished papers and appear in their records as ‘Series 01: Miles Franklin unpublished manuscripts, 1908-1947, undated; call number MLMSS 6035/1-19 and Miles Franklin papers, mainly literary manuscripts, [1900-1954?] call number MLMSS 445’.[9]

I sought further clarification from the Mitchell Library regarding copyright and was advised by the Librarian, that, ‘as far as I am aware, the textual manuscript materials within these collections remain in copyright. I have established contact with a representative of Perpetual Limited, who have been vested with the copyright for the material within these papers.’[10] I sought clarification via email and telephone from Perpetual Limited. I was advised the matter would need to be elevated to the lawyers and some two months later, with apologies for the delay, was informed by the Trustees that, ‘In relation to your query, Perpetual is not aware of the origin or nature of the works you refer to below and is unable to assist with your enquiry’.[11]

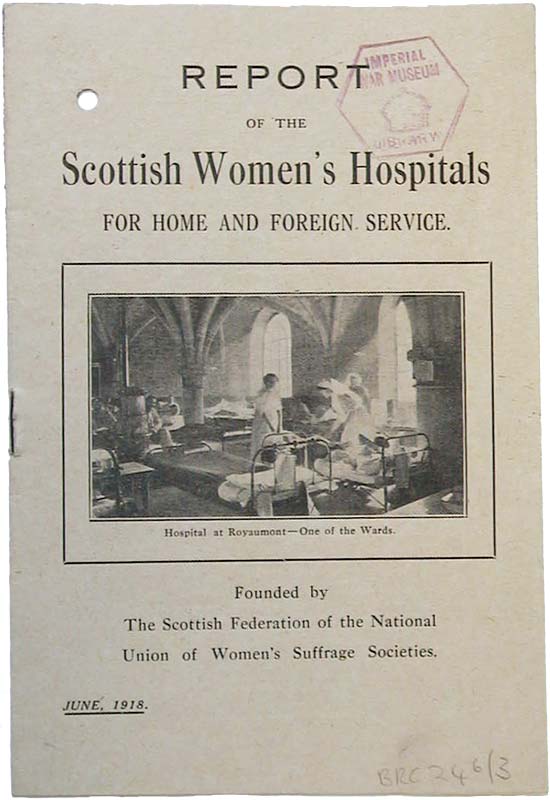

Scottish Women’s Hospitals report, 2018 (National Archives UK/Imperial War Museum)

Scottish Women’s Hospitals report, 2018 (National Archives UK/Imperial War Museum)

I pursued the 2014 Special Issue of Transcultural Studies on line at the URL on the Imprint Page, www.plenumpublishing, searched for the relevant issue, clicked on the title, and received the message: ‘This account has been suspended.’[12] (Searching for other issues of Transcultural Studies gets the same result.) I had hoped to locate details of the copyright holder but have once again been thwarted.

I have not been able to visit the Mitchell Library Archives but would be interested to view the other materials from Franklin’s time in the Balkans that Jill Roe[13] enumerates as including a ‘further four discrete and fragmentary sketches, at least two contributions to a camp magazine (yet to be traced)’, and a fragment, ‘Zabranjeno’ (Forbidden Valley) related to the play ‘By Far Kajmachtchalan’, which appears in Transcultural Studies (p. 109-147); plus post cards.

Genre?

My next concern arises from Slobodanka Vladiv-Glover’s essay ‘An unknown Australian war novel: Miles Franklin’s “Six months with the Serbs”’, published as ‘Commentary’ in the Special Issue of Transcultural Studies (pp. 148-168). This article raises the question of how are we to read Franklin’s Serbian sketches: history, fiction, a novel, a war documentary, a creative blurring of genre? Slobodanka Vladiv-Glover makes a case for the sketches being an ‘Australian World War One Novel’ and discusses the Balkan materials in the context of Franklin as an Australian writer of ‘the soil’, in the form of a ‘sketches of manners’.[14] ‘It is the personalized emotive point of view, described as “Australianism” which imparts unity to the sketches and gives grounds for calling Six Months with the Serbs an Australian war novel’, writes Vladiv-Glover (p. 148).

Vladiv-Glover’s essay will be of interest to Franklin scholars and, while I am in broad agreement with much of her analysis, I take issue with classing the sketches as ‘fiction’ or a ‘novel’. Vladiv-Glover writes, ‘It would be easy to mistake this fiction for actual history because it is, like history, a narrative written from a personal point of view’ (p. iii). To be sure, Franklin makes modest claims as a humble observer of Serbs during her six-month stay and no doubt she has taken licence with some of her characters, but the events recounted and the chronology are consistent with her diaries and other documentation.[15]

I have found it useful to read the manuscript as a form of creative ethnography and indeed there is a body of critical feminist theorising concerning this genre.[16] In signing up to work with the Scottish Women’s Hospitals, Franklin had undertaken not to publish anything concerning her wartime service.[17] Her ‘comments of a camp cook’ (p. 1) do not violate this undertaking but rather allow her observations to be inflected by wry humour, compassion, and a sense of shared humanity, while alerting us to critical discourses of the period and, in the context of today’s refugee crisis, offering another lens through which to view Europe, old and new.

Finally, I am not sure how to read the designation of the manuscript as ‘unknown’? Hugh Gilchrist wrote of ‘Miles Franklin in Macedonia’ in 1982.[18] Jill Roe devotes a chapter to the manuscript and its context in her biography of Franklin.[19] In his latest non-fiction book, Three Brilliant Careers, Ross Davies tells the story of celebrated writer Miles Franklin and two lifelong Australian friends, Nell Malone and Kath Ussher, who served in the Balkans with the Scottish Women’s Hospitals in World War I and later gained fame and success in their respective careers.[20] The manuscript was known but it was not known as a novel of World War I. Jill Roe considers the range of Franklin’s unpublished Balkan materials, ‘because of its documentary character’, to be a ‘significant source of information and insight into what might otherwise remain a largely inaccessible experience’.[21]

Nemari ništa (It matters nothing) is a constant refrain throughout Franklin’s account of her ‘Six Months with the Serbs’. Au contraire, it does matter.

* Diane Bell is a writer, anthropologist and social justice advocate. She is Professor Emerita of Anthropology at George Washington University, DC, USA and Writer and Editor in Residence at Flinders University, South Australia. She currently lives in Canberra, Australia, where she continues as an independent scholar to work on Native Title projects and writing. She has published widely on matters of anthropology, history, law, religion, the environment, feminist theory and practice. Her award-winning books include Generations: Grandmothers, Mothers and Daughters (1987), Daughters of the Dreaming (1983, 1992, 2002), and Ngarrindjeri Wurruwarrin: a World that Is, Was, and Will Be (1988, 2014). Her previous reviews for Honest History have been of Chris Walsh’s book Cowardice and Raden Dunbar’s Secrets of the Anzacs.

* Diane Bell is a writer, anthropologist and social justice advocate. She is Professor Emerita of Anthropology at George Washington University, DC, USA and Writer and Editor in Residence at Flinders University, South Australia. She currently lives in Canberra, Australia, where she continues as an independent scholar to work on Native Title projects and writing. She has published widely on matters of anthropology, history, law, religion, the environment, feminist theory and practice. Her award-winning books include Generations: Grandmothers, Mothers and Daughters (1987), Daughters of the Dreaming (1983, 1992, 2002), and Ngarrindjeri Wurruwarrin: a World that Is, Was, and Will Be (1988, 2014). Her previous reviews for Honest History have been of Chris Walsh’s book Cowardice and Raden Dunbar’s Secrets of the Anzacs.

_____________________

[1] In the original manuscript, Franklin writes ‘Ne Mari Nishta’ and that is how the document is referenced in the Mitchell Library. In the edited version in Transcultural Studies, Franklin’s intuitive orthographies for the words from the various languages she heard being spoken in the Balkans have been standardised. The title appears as ‘Nemari Ništa’ and is not italicised. My in-text page numbers refer to Transcultural Studies.

[2] Jill Roe, ‘Franklin, Stella Maria Sarah Miles (1879–1954)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 8, MUP, (1981). https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/franklin-stella-maria-sarah-miles-6235

[3] See p. 41, n. 28; the term usually referred to pro-Bulgarian irregulars in Macedonia.

[4] Jill Roe, Stella Miles Franklin: A Biography, Fourth Estate, Sydney, 2008, p. 207.

[5] ibid., 2008, p 221.

[6] The song has many versions. The one I am suggesting may have been in Franklin’s ear was The Yankee Doodle Boy based on the traditional U.S. tune Yankee Doodle Dandy, penned by George M. Cohan some thirteen years before America’s entry into World War. The song was part of Cohan’s highly successful Broadway musical Little Johnny Jones. The verse I learned as a child is his: ‘I’m a Yankee Doodle Dandy/ A Yankee Doodle, do or die/ A real live nephew of my uncle Sam’s/ Born on the Fourth of July/ I’ve got a Yankee Doodle sweetheart/ She’s my Yankee Doodle joy/ Yankee Doodle came to London/ Just to ride the ponies/ I am a Yankee Doodle boy.’ <https://www.firstworldwar.com/audio/yankeedoodleboy.htm>

[7] <https://www.acmssearch.sl.nsw.gov.au/search/itemDetailPaged.cgi?itemID=100036>

[8] <https://acms.sl.nsw.gov.au/item/itemDetailPaged.aspx?itemID=423047>

[9] I am quoting from an email response from the State Library of NSW ‘IR203040’, 19 August 2015 which was further to correspondence IR202886 of 10 and 11 August 2015, all of which confirmed the two locations of the Franklin manuscript. I also spoke with staff in the State Library, 5 and 6 August 2015.

[10] Email response from State Library of NSW ‘IR203040’, 19 August 2015.

[11] Email from Perpetual Trustees, 3 November 2015, in response to my inquiry, 21 August 2015.

[12] <https://www.transculturalstudies.com/InterdisciplinaryResearch>

[13] Roe, op.cit., 2008, p. 213.

[14] Slobodanka Vladiv-Glover, Adjunct Associate Professor, School of Languages, Literatures, Cultures and Linguistics, School of Arts, Monash University, studied Russian, French and German at the University of Melbourne for a BA Honours degree, then completed an MA on the Russian 19th century novel. <https://profiles.arts.monash.edu.au/millicent-vladiv-glover/> Her perspective as a Dostoevsky and Bakhin scholar brings welcome comparative insights to Franklin’s writing.

[15] See Roe, op.cit., 2008, p. 212-223; see also Diary Entry, 11 August 1917: ‘In evening patients were entertained at simple games. How very simple the male of the species is. With him running the planet, little wonder it is being run off its axis.’ (Cited in Paul Brunton, (ed.), The Diaries of Miles Franklin, Allen and Unwin. 2004, p. xx, n. 17, from Miles Franklin’s papers, Mitchell Library: ML MSS 364/2/10).

[16] See N. Lutkehaus, ‘Margaret Mead and the “Rustling-of-the-Wind-in-the-Palm-Trees School”’, in Behar and Gordon, (eds), Women Writing Culture, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1995, pp. 186–206, regarding women’s evocative and experimental ethnographic writing; for further context see Diane Bell, Pat Caplan and Wazir Jahan Karim, (eds), Gendered Fields: Women, Men and Ethnography, Routledge, London, 1993.

[17] Roe, op.cit., 2008, p. 213.

[18] See Abstract, Quadrant, Vol. 26, Issue 8, Aug 1982: ‘Stella Miles Franklin’s reticence about her life abroad during the first World War has been a subject of speculation, and recently of study. There is no great mystery, however, about her experiences as a hospital cook in Macedonia from July 1917 to February 1918, which are candidly recalled in her series of sketches Ne Mari Nishta: Six Months with the Serb, signed “Miles Franklin, Outlander”. Largely an account of daily life under canvas in a two hundred-bed field hospital staffed by women and attached to the Serbian army in Greece, its interest today lies more in confirmation of its author’s character than in any major literary merit or historical significance.’ <https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=427653565551958;res=IELLCC>

[19] Roe, op.cit., 2008, pp. 198-224.

[20] See the blurb for Ross Davies, Three Brilliant Careers: Nell Malone, Miles Franklin, Kath Ussher, Boolarong Press, Salisbury Qld, 2015, where he claims to reveal ‘the previously untold story of celebrated author Miles Franklin and two lifelong Australian friends, Nell Malone and Kath Ussher, who met in Chicago in 1914 and reunited a year later in war-torn London’. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=_54aBgAAQBAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s .s

[21] ibid.

Diane Bell responds:

To John von Sturmer: Certainly Miles Franklin sensibilities are Australian, deliciously so: the landscape, language, larrikin, it’s all there. And, she was not alone. Amongst Franklin’s friends, colleagues and co-workers were other women born in Australia who had sought ‘brilliant careers’ inside and outside Australia; who drew on their Australian experience; who travelled widely; who were familiar with the ideas and actions of their international sisters, especially in the UK and USA; and who were part of the struggle for women’s rights, for peace, for just working conditions, and for a world in which they could live lives of purpose and meaning.

Fortunately there is an ever growing body of literature that offers a window onto the vibrant and varied community into which Franklin was welcomed in London and Chicago and its deep roots in Australia. Dip into Jill Roe’s biography, Stella Miles Franklin (2008), or Ross Davies’ Three Brilliant Careers (2015) that follows the lives and careers of trailblazing Australian women, Miles Franklin, Kath Ussher, and Nell Malone. With reference to the manuscript under review we have the matron, Dr. Agnes Bennett (1872-1960), born Neutral Bay, medical practitioner, and in 1915 the first woman commissioned as a British Officer in WWI. She is running the Scottish Women’s Hospital at Ostrovo 1916-17, during Franklin’s service (https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bennett-agnes-elizabeth-lloyd-5206).

What I find fascinating with respect to the context of Franklin’s WWI service is the ways in which she was part of the feminist debates around conscription that reached across the Atlantic and Pacific. We should note the campaigning and speeches in England and the USA of Australian friend Vida Goldstein (1866-1949), born Portland Victoria, ardent feminist and pacifist and then there was Vida’s work with Adela Pankhurst (1885-1961) who unlike her mother Emmeline and sister Chrisabel, was anti conscription. Alice Henry (1857-1943), feminist, trade unionist, born Richman Victoria, welcomed Franklin to the US in 1906. These were women who cast formidable shadows.

Why wasn’t ‘Ne Mari Nishta’ published? As I noted in the review, Franklin was not permitted to publish while volunteering with the SWH but she did seek to publish the sketches of her six months with the Serbs in April 1918. She was unsuccessful. It is important to remember that Franklin’s My Brilliant Career was rejected in Australia. On Dearborn Street and My Career Goes Bung languished in want of a publisher for decades. Why? In part I think it was that Franklin was writing across genre as were a number of women of the period. They had journalistic and literary skills; they wrote from first hand experience; they were part of the scene of which they wrote. Not the classic ‘objective’ reporter; too feminine, emotional, subjective. I prefer to see this writing as that of ‘engaged insiders’, what I have dubbed ‘creative ethnography’ in the review above. Franklin’s vivid sketches were of the moment. The war moved on. However, as I have argued, they still matter. Then there was the perception of parochialism: in the US she was too Australian, in England too American.

Diane Bell responds to Leighton View who wrote: ‘The forensic research trail is engrossing as well.’ Well, I am still on the case and will be posting further details as they become available.

The abrupt end of the online publishing trail with the message that ‘this account has been suspended’ on http://www.plenumpublishing now has a new trail and hopefully a link will be provided to the new online location at Brill Online Books and Journals at https://booksandjournals.brillonline.com/content/journals/10.1163/23751606-01002001 where the issue is now archived. Brill bought the journal from Charles Schlacks at the end of 2014. All issues from 2015 onwards belong to Brill, as do the archives from 2014 to 2006.

Should you want to read the article, it will cost you $30.00. So an unpublished manuscript is now behind a pay-wall.

Diane Bell responds to msawer: Check back later – more work for Sue Grafton.

Most interesting …. and very enlightening. The forensic research trail is engrossing as well. Grand!

Diane Bell’s rigorous scholarship and attention to detail in her review of Franklin’s social commentary highlights what Australian women writers bring to the genre. Bell has awakened me to Franklin’s strong-mindedness, intellect and energy and the not-so-sheltered life she lived with her adventurous travels. The article brings out Franklin’s unique perspective of Australian idiom and her delightful sense of humour and inventiveness of language which she used to project her distaste for the unfair and absurd in our society.

Ann Moyal provided this comment:

I found Diane Bell’s essay fascinating, excellent historically, sociologically and anthropologically, a great accomplishment in itself and a great place to bring it to the public gaze.

An interesting and considered review. I was especially taken by the suggestions of a conscious ‘Australianness’ on Franklin’s part – and wonder how characteristic this was of the age. I’ve always been intrigued by the way in which Australians, via war, encountered ‘the other’ – and worlds not Anglo. This phenomenon is intensely interesting – and must have had a powerful impact on the Australian imaginary. While the British orientation, if we can call it that, has remained very powerful and surprisingly active, even at the present time, Franklin’s text seems important in ‘re-arranging’ the ‘Australian view’. But how come it wasn’t published? Is this prejudice or merely disinterest – and if the latter, why? I wonder how Serbs – both in Australia and in Serbia – would respond to Franklin’s text now. Australians adore the ‘overseas view’ – the view from afar. I wonder how general this phenomenon is.

Fascinating detective work – like reading the latest Sue Grafton!