‘The eighties in nine chapters’ (review of Bongiorno), Honest History, 1 December 2015

Janet Wilson* reviews The Eighties: The Decade that Transformed Australia by Frank Bongiorno

__________________________

Among the words and phrases that entered the lexicon in the 1980s are these, in no particular order: Australia Card, safe sex, hackers, Star Wars, power dressing, The Age tapes, AIDS and HIV, efficiency dividends, APEC, structural adjustment, the clever country, nouvelle cuisine, the HR Nicholls Society, Sanctuary Cove, urban renewal, and the Doug Anthony All Stars. In this excellent description and dissection of the 1980s Frank Bongiorno discusses all of them. The questions that climaxed in the 1980s (personal intimacy, national identity and Australia’s economic future) remain unresolved, along with the tensions between globalisation and national sovereignty, the American alliance and our geographic position in Asia, settlers and Indigenous Australians and, above all, how to reconcile efficiency and productivity with the need to maintain social justice ideals and a reasonable standard of living.

Among the words and phrases that entered the lexicon in the 1980s are these, in no particular order: Australia Card, safe sex, hackers, Star Wars, power dressing, The Age tapes, AIDS and HIV, efficiency dividends, APEC, structural adjustment, the clever country, nouvelle cuisine, the HR Nicholls Society, Sanctuary Cove, urban renewal, and the Doug Anthony All Stars. In this excellent description and dissection of the 1980s Frank Bongiorno discusses all of them. The questions that climaxed in the 1980s (personal intimacy, national identity and Australia’s economic future) remain unresolved, along with the tensions between globalisation and national sovereignty, the American alliance and our geographic position in Asia, settlers and Indigenous Australians and, above all, how to reconcile efficiency and productivity with the need to maintain social justice ideals and a reasonable standard of living.

Bongiorno defines the 1980s as the years between the election of the Hawke Government in March 1983 and Hawke’s defeat by Keating in the Caucus ballot in December 1991. Bongiorno himself was 13 or 14 at the beginning of this period and 21 or 22 at its end; unlike many others who have written of the period it is because he was neither one of the players nor in the Parliamentary Press Gallery that he is able to reflect on the decade from a fresher perspective.

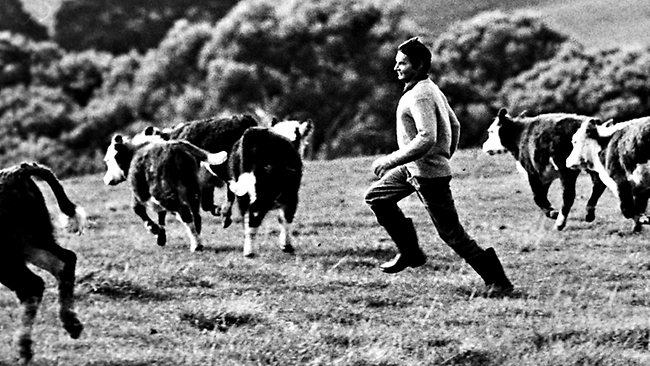

The book’s nine chapters take a thematic approach rather than a strictly chronological one and Bongiorno begins (in a chapter called ‘A good run’) with the Ash Wednesday fires in Victoria and South Australia, the campaign for the 1983 election and a comprehensive and sympathetic account of the Combe-Ivanov saga, which began over dinner at the Russian diplomat’s home on election eve, 4 March 1983. The chapter then covers the drought and, at some length, the story of Cliff Young’s run in the Westfield Sydney-Melbourne Ultramarathon. Cliff was ‘the farmer who lived with his old mum, grew spuds, and trained in gumboots while herding cows’ (p. 29). For Bongiorno he was ‘the hero who emerged from farm and forest to remind the nation of its soul’ (p. 31).

The second chapter deals with the float of the dollar, with Alan Bond’s career, including his real estate venture at Yanchep, north of Perth, with the Western Australian state government’s support; to increase Yanchep’s appeal he arranged for some of the starkly white sandhills to be painted green for the photo ops. Later sections of the book cover race relations, the debates about land rights and the roles of Geoffrey Blainey and John Howard in elevating anxiety about Asian migration. It was too early for Pauline Hanson to feature, but events and comments of the last couple of weeks show that little has changed.

Christopher and Pixie Skase (Daily Telegraph/Rennie Ellis)

Christopher and Pixie Skase (Daily Telegraph/Rennie Ellis)

In the ‘Deal makers’ chapter Bongiorno deals in depth with the complex manoeuvrings of the big players (Robert Holmes à Court, Kerry Packer, Alan Bond) the publication of BRW’s Rich Lists and the debate over media ownership. Among the less well-remembered rogues and the members of the white shoe brigade whose careers he describes is John Friedrich, who took over the National Safety Council of Victoria in the early 1980. The Council collapsed in 1989 and Friedrich’s considerable frauds were uncovered. Bongiorno’s description of the scope of the NSCV’s assets at the time typifies his marvellous style which brings to life, and brings humour to, otherwise dry situations: not only did the organisation have 22 helicopters, 10 aeroplanes, a midget submarine and ‘much else that was shiny, flashy and expensive’ (p. 140), there was also a fleet of dogs to be parachuted into search areas and a flock of pigeons in training for search and rescue missions.

Most of these players, and others including Christopher Skase, Laurie Connell of the Rothwells Merchant Bank, George Herscu, Richard Pratt and Larry Adler, reappear in ‘The crash’, the final chapter. Here Bongiorno covers the effects of the stockmarket crash, both at an individual and an institutional level. He discusses the unravelling of the long Bjelke-Petersen era in Queensland and the establishment of the Fitzgerald Commission, the problems of the state banks of South Australia and Victoria, and the collapse of the Pyramid Building Society. He concludes with the release of Fightback! and the culmination of the conflict over leadership between Hawke and Keating in the Caucus ballot on 19 December 1991.

Bongiorno’s examination, particularly in his chapters dealing with the rising anxiety about environmental changes (which he suggests raised the prospect of a catastrophic future, rather as the threat of nuclear war had done) and the rise of the New Right and its influence on the dramatic industrial disputes of the time (Dollar Sweets, South East Queensland Electricity Board, Mudginberri and Robe River) bring back the details and implications for those whose memories falter a little. They also inform younger readers about a tipping point in industrial relations.

Ian Macphee (Psephos)

Ian Macphee (Psephos)

Bongiorno covers briefly the complicated merry-go-round of Liberal Party preselections in Victoria in 1989, around the time of the change in leadership from Howard to Peacock. These upheavals resulted in Ian Macphee, the moderate member for Goldstein, being replaced by David Kemp, one of the leading members of the New Right, the dries of the Party, and Roger Shipton being replaced in Higgins by Peter Costello. The wounded Macphee tried for preselection in Deakin, which had been vacated by Julian Beale in order to move to Bruce, where he dislodged Ken Aldred, who then turned up as another candidate for Deakin. Macphee lost to Aldred who was one of the more extreme members of the right in the Victorian Liberal Party. The liberal wing of the Liberal Party has never really recovered.

Bongiorno’s style is effective, enlivening a description of a player or event with a wry phrase or quotation. On Alan Bond boasting of his fluency in four languages Bongiorno quotes the comment of a former Bond employee that Bond could barely speak English; the author suggests that Bond’s early career as a signwriter was hampered by his poor spelling. Bond’s claim that Australia would win the America’s Cup ‘just like we did at Gallipoli’ was not reassuring to anyone who had paid more attention than he had in history lessons at school (p. 55). Again on Bond, this time on his bid to take over Castlemaine Tooheys to add to his Swan Brewery, ‘it was widely believed that one could not go broke selling beer to Australians, but Bond was already a man famous for flouting received wisdom’ (p. 124).

‘The Hawke Government’, in an earlier chapter, ‘combined an economic policy, increasingly geared towards the financial markets with a social policy that was recognisably Whitlamite – at least if you were prepared to squint a little’ (p. 56). Bruce Ruxton sported a ‘haircut that would have passed muster in Moratai back in 1945’ (p. 62). Don Lane, one of the several Queensland National Party ministers later convicted and gaoled for corruption, named Lionel Murphy in the Queensland Parliament as the High Court judge referred to in The Age tapes; Bongiorno describes Lane as one of the Queensland Parliament’s ‘most corrupt politicians in a competitive field’ (p. 101). Finally, he quotes a Brisbane architect describing Christopher Skase’s office as a ‘post-modernist Roman bath house, the stone having been mined in Brazil, polished in Italy and imported especially for Qintex’ (p. 126).

Bongiorno uses a wide range of sources, from contemporary newspaper reports to biographies and the text of television advertisements. They include Hugh Mackay’s work, allowing the author to ground his discussion on qualitative research. The book is a reminder also of the influence at that time of The National Times and the ABC’s investigative reporting, particularly the work of Chris Masters in exposing some of the dodgy dealers and dealings of the decade.

In his afterword Bongiorno challenges the frequently put view that, while the 1980s was undoubtedly a decade of excess and greed, it was also a time of necessary economic transformation. He argues that, although the rest of the English-speaking world and France experienced a ‘retreat of the state’ in the 1980s with deregulated financial markets, the internet, economic liberalism and consumerism combining to change the way international financial relations operated, the way the Hawke Government managed those changes was distinctly different; it did more than Britain and the US to retain principles of social justice by maintaining spending on social security and it was firm in its determination to keep a continuing role for unions in industrial relations.

Cliff Young training in the paddock (The Australian)

Cliff Young training in the paddock (The Australian)

In this scholarly, finely researched, referenced and indexed work Frank Bongiorno brings together the events and influences of the 1980s in an engaging and entertaining manner. Each chapter ends with a pithy summary of the events covered and a lead-in to the next. He is to be congratulated for producing such a valuable work.

* Janet Wilson was formerly a researcher in the Politics and Public Administration Section of the Parliamentary Library, Canberra. She reviewed Julie Summers’ Fashion on the Ration for Honest History.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.