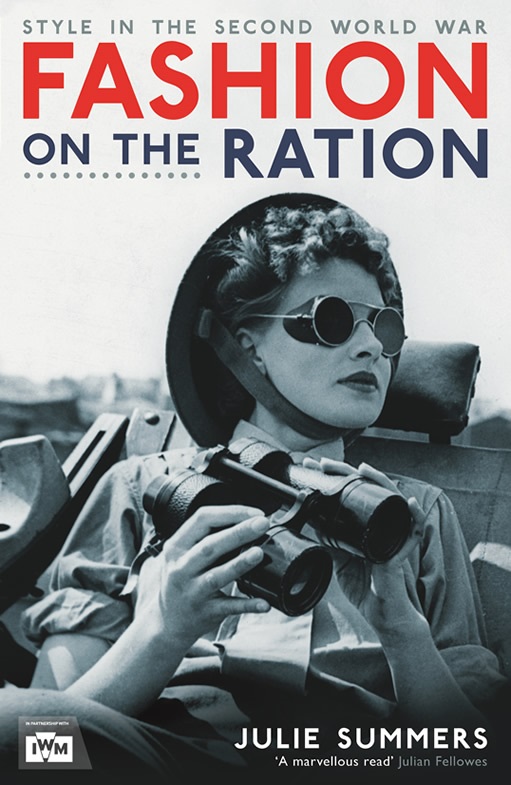

‘Finding a thing to wear during World War II’, Honest History, 1 September 2015

Janet Wilson* reviews Fashion on the Ration: Style in the Second World War by Julie Summers

This book accompanied an exhibition at the Imperial War Museum in London; the exhibition closed on 31 August. It showed photography, posterns, newsreels, advertisements, magazines and letters, plus some of the garments made and sold during the rationing period. It was based on the collection of wartime utility clothing gathered by Frederic A. Sharf in Boston. The book is an engaging and rewarding read, packed with information and anecdotes drawn from diaries, letters and published sources, and containing photographs of garments from the exhibition.

By April 1940, there was in principle agreement in the British War Cabinet for the introduction of a scheme for standard clothing and footwear to minimise the consumption of fabric for civilian clothing. The entire wool clip from Australia and New Zealand, and most of South Africa’s, had been bought by the government for military use and for the export trade, leaving little over for civilian clothing. By October 1940, the need for parachutes meant that raw silk was no longer available for civilian use and the consequent limited supply of hosiery gave the women of Britain the first taste of austerity.

By April 1940, there was in principle agreement in the British War Cabinet for the introduction of a scheme for standard clothing and footwear to minimise the consumption of fabric for civilian clothing. The entire wool clip from Australia and New Zealand, and most of South Africa’s, had been bought by the government for military use and for the export trade, leaving little over for civilian clothing. By October 1940, the need for parachutes meant that raw silk was no longer available for civilian use and the consequent limited supply of hosiery gave the women of Britain the first taste of austerity.

While the Blitz continued, secret plans were being made by the Board of Trade to estimate the clothing needs of the population in wartime; many women’s organisations were consulted and were in favour of rationing. Churchill was as opposed to clothes rationing as he had been to food rationing, not wanting to see the public in rags and tatters, but Summers relates how the decision to launch rationing coincided with the hunt for the Bismarck, when Churchill was otherwise preoccupied.

Summers approaches her topic chronologically and gives an excellent description of the fashion scene leading up to the war, including the involvement of top designers like Norman Hartnell and Hardy Amies with designs for paper patterns, and garments for the mass market which were designed to raise the profile of the utility scheme. Women’s magazines were also influential in setting the style.

When rationing was introduced from 1 June 1941 the aim was to cut clothing consumption to two-thirds of the pre-war level. Initially 60 coupons were allocated per adult per year: 7 for a dress or skirt; 14 for a winter coat; 3 for knickers, corsets or an apron. Anomalies abounded: eight coupons for men’s trousers, unless they were made of corduroy, in which case you needed just five, and hats were not rationed at all, along with furnishing fabric and blackout material. Although the scheme was applied universally it was much harder for the lower paid who tended to have fewer clothes to begin with, unlike the well-off, who had massive wardrobes that would last them the year.

The bureaucracy to administer the scheme was enormous and the description of goods complex: one coupon would buy a pair of men’s half hose (not woollen) or a pair of ankle socks not exceeding eight inches from point of heel to top of sock when not turned down. Special coupon arrangements were made for children during growth spurts, for school uniforms and for second-hand clothing.

With the fall of Singapore in February 1942 the number of coupons was reduced and further regulations relating to design were introduced to save even more cloth: the number of seams and pleats in women’s garments was limited, turnups on men’s trousers were outlawed (and debated in the House of Commons) and boys under 13 years of age could not wear long trousers.

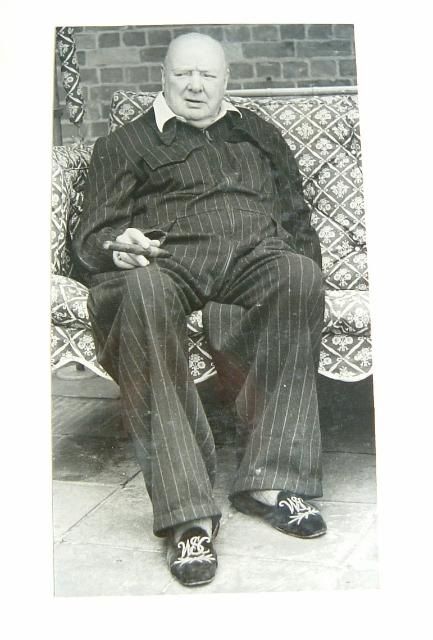

Churchill’s contribution to fashion (Churchill Central/Churchill Archives/Broadwater Collection)

Churchill’s contribution to fashion (Churchill Central/Churchill Archives/Broadwater Collection)

Summers presents impressive statistics showing the saving in cloth the utility look achieved from the end of 1941, as well as the labour saved by limiting the number of buttons on suits, shirts and dresses. She deals with women in uniform and there is a chapter devoted to underwear, and corsets in particular (‘Supporting Britain’s women’), in which she describes the ingenuity with which women faced the shortage of elastic and unpicked downed pilots’ parachutes to make knickers out of the silk. Another chapter describes how women managed with the shortage of cosmetics.

In the chapter dealing with ‘Make-do and mend’ (an objective much more achievable in an era when most women could sew – it was only the very rich or the poorest who couldn’t turn a collar or darn a sock) she quotes from the Board of Trade’s Make-Do and Mend booklet published to instruct women on how to make clothes last longer and how to unpick and remake, unravel and re-knit. The Women’s Institute published an article suggesting members could use a wire brush to collect hair from dogs, then spin the hair in the usual way; collies, sheepdogs and Pekinese were preferred, whereas poodle, Labrador and spaniel hair was problematic. The last chapter of the book describes the situation for demobbed servicemen and women and the way the British fashion industry gradually recovered, even though clothes shortages continued for some years after VE Day.

The author captures the atmosphere of early enthusiasm for doing one’s bit for the war effort. People managed relatively well until 1943-44 when shortages were even more acute and when even the women’s magazines stopped offering cheery advice but tried to persuade their readers not to despair. Perhaps the manufacture of a Clarks’ shoe with a hinged wooden sole was the last straw. The book is peppered with interesting stories of how people managed when soap and shampoo were unavailable, of the scheme devised by Barbara Cartland to establish a wedding-dress lending service, and some familiar ones like the hazards of painting legs and drawing a seam up the back when the only stocking options available were baggy lisle utility numbers.

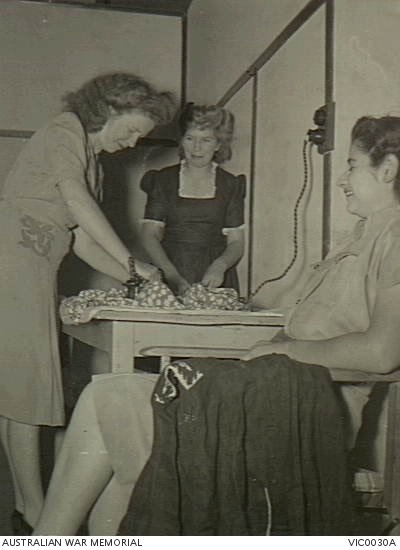

In Australia, clothes rationing was not as neatly handled as in Britain, being preceded by a quota system to reduce weekly sales to 75 per cent of the previous year. The intention was to curb hoarding but the fear of shortages meant shops were subject to stampedes and shopping frenzies. In June 1942, rationing was introduced and, in common with Britain, designs were introduced to save fabric. John Dedman, the Minister for War Organisation of Industry, a dour Scot at the best of times, modelled the Victory suit for men, but little could enhance the appeal of this single-breasted suit with no waistcoat, no trouser turnups nor button on the sleeves.

‘WAAAF personnel’ ironing their civilian clothes, YWCA Leave Hut, Mildura, Vic., c. 1943 (Australian War Memorial VIC003oA)

‘WAAAF personnel’ ironing their civilian clothes, YWCA Leave Hut, Mildura, Vic., c. 1943 (Australian War Memorial VIC003oA)

In 1943, the Commonwealth Rationing Commission published its booklet New Clothes from Old, which gave detailed instructions and patterns for transforming old clothes into new outfits, including cutting the pieces carefully to avoid worn areas. The booklet included a message to the women of Australia from Prime Minister John Curtin urging them to patch and mend and suggesting that ‘the darning needle is a weapon of war’. The booklet also contained the slogan, ‘Give Tojo a blow, make, mend and sew’. This aspect of wartime social history is covered by Kate Darian-Smith in On the Home Front: Melbourne in Wartime 1939-1945 (Oxford, 1990) and in Michael McKernan’s All In: Australia during the Second World War (Nelson, 1983).

* Janet Wilson was formerly a researcher in the Politics and Public Administration Section of the Parliamentary Library, Canberra.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.