‘La nef des fous: review of Dunbar’s Secrets of the Anzacs‘, Honest History, 12 May 2015

Diane Bell* reviews Raden Dunbar, The Secrets of the ANZACS: the Untold Story of Venereal Disease in the Australian Army, 1914-1919. (La nef des fous = the ship of fools.)

During World War I, millions of soldiers and women from all combatant nations became infected with venereal disease during an unprecedented outbreak of wartime sexual promiscuity. Included were at least 60 000 Australian soldiers, who were treated by army doctors for venereal infections between 1914 and 1919 in Egypt, the UK, France, and in Australia. So begins Raden Dunbar’s revelation of The Secrets of the ANZACS (p. vii).

This is a story that needs to be told. It’s a story that bites hard in this, the centenary year of the Anzac landing at Gallipoli and associated celebrations. It’s a story that illustrates the age-old adage of truth being the first casualty of war. It’s a story that reaches into the lives of many Australians who fought, concealed and suffered, who were variously spurned and celebrated, humiliated and honoured. It reaches into the lives of the commanding officers, medicos, journalists, politicians and feminist campaigners who confronted the folly of adopting a punitive moral approach to what would eventually come to be managed as a medical problem. Like a whisper in a forsaken canyon, the story reverberates through the lives of the families of soldiers, their descendants and communities, is deflected by military codes of conduct and class privilege, and is heard in snatches on national and international stages.

VD hospital, Langwarrin (Australian War Memorial A03402)

VD hospital, Langwarrin (Australian War Memorial A03402)

Dunbar’s interest in telling this story was sparked by reading Bad Characters, historian Peter Stanley’s account of the hidden aspects of the Australian Imperial Forces (AIF).[1] Drawing on a wide range of sources, Dunbar sets out the dilemma that the VD outbreak in Egypt in 1915 constituted for the military. The AIF hospitals needed beds for the casualties of Gallipoli, so the malingering VD patients were ‘back loaded’ onto boats bound for Australia. But this is just the beginning of the story.

Details of Dunbar’s great uncle’s war years spurred Dunbar on to explore the context in which Ernest Dunbar, born in Scone in the Hunter Valley of New South Wales, enlisted as John Dunbar and was sent to the front. Wounded at Gallipoli, he was sent to convalesce in Alexandria and, with back pay in hand, explored the out of bounds ‘Sister Street’ where he contracted gonorrhoea. Along with some 274 other ‘patients’ he was sent home on the troopship A18 Wiltshire to the newly established ‘facility’ for VD patients at Langwarrin, on the Mornington Peninsula, Victoria.

After six weeks of brutalising treatment, the ‘cured’ soldier was sent to retrain. He absconded and a warrant was issued for his arrest. While the authorities pursued John Dunbar, Ernest reenlisted as John Beech and was sent back to the field where a German mustard gas shell landed him in an English hospital. As Beech he recorded the lives of young soldiers in sketches that enliven the book under review and now hang in the Australian War Memorial.

As John Beech, too, Dunbar returned to France but, this time, shell shock and ‘trench feet’ saw him returned to Australia. He now needed an army pension to survive but first his multiple identities and deeds had to be reconciled: Ernest Dunbar to his family, absconder John Dunbar to the Army and artist John Beech to the public. Dunbar ‘confessed’ to his various aliases; his wounding at Gallipoli and gassing at Passchendaele were now part of the one record.

However, Raden Dunbar’s great uncle did not live to enjoy the ‘benefits’ that were due him from his service. In late 1924 he was diagnosed with both heart disease and cancer. He died on 25 January 1925, just ten years after he first volunteered and five years after his discharge in Sydney. He never married. John Dunbar lies today where he was buried as a pauper in an unmarked grave in Cheltenham Cemetery, Victoria.

Sketchbook of John Beech (Dunbar) (Australian War Memorial ART94463)

Sketchbook of John Beech (Dunbar) (Australian War Memorial ART94463)

This is but one of the remarkable stories presented by Raden Dunbar of the overwhelmingly naïve, unprepared, gung-ho larrikin lads who served with distinction but whose medical condition had far-reaching social and economic consequences. It was an offence to conceal VD; its victims were guilty of misconduct. As punishment, their pay was stopped for the duration of their treatment, a brutal regime of injecting and syringing with toxic cocktails. Without explanation, families at home found themselves denied the allotted portion of their provider’s pay. Further, because pre-marital and extra-marital sex was deemed to be the indulgence of moral weaklings, the afflicted were to be shunned by society and designated as sinners by the church.

In Chapter One we meet Lieutenant-General Sir William Birdwood, who ordered Major-General Bridges to stop the VD outbreak. Birdwood in turn called upon Captain Charles Bean, the newspaper correspondent accompanying the AIF, and together they pursued the methods of Birdwood’s mentor Lord Kitchener of Khartoum. Preferring the austere puritanism of Kitchener to the more pragmatic acknowledgement of the need to ensure their soldiers were fit to fight, they instigated a regime of physical training, chaplaincy-led lectures, and sobriety-Christian chastity pledges. Of particular interest for contemporary debates regarding ‘embedded journalism’ are the shifting sands of the story, as Bean records what he sees and then writes articles fit for purpose.

In Chapter Two Dunbar sets out the dilemma faced by James Barrett, who was prepared to advocate for prophylactics, and John Brady Nash, who assumed the unenviable task of selecting which patients would be sent home, as they shaped regimes at the isolation-detention barracks at Abbassia. This was not at all the contribution to the war effort that these medical men had anticipated.

Chapters Three and Four trace the human dramas, tinged with comedy, of the voyage of the Wiltshire, which Dunbar labels ‘la nef des fous’ and the subsequent conditions of the ‘inmates’ at the isolation-detention barracks at Langwarrin, dubbed a ‘concentration camp’. Managing the ‘story’ of the facility was a PR nightmare as breakouts, courts-martial, parliamentary discussions and media stories alerted locals to the presence of ‘infected men’ in their midst. Parents and wives began arriving at the gates of the camp. Slowly, under the new commandant, General Williams, the criminalisation of the men shifted to more humane medical treatment, with wholesome social activities, landscaping of the grounds, an ornamental fountain of Venus, a shower block with hot water, a military brass band, and visits from locals. By December 1916 escapes and absences had practically stopped.

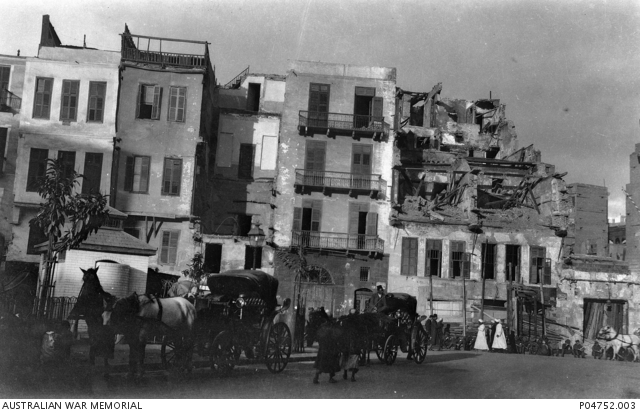

Ruined building in Cairo’s Wagh-el-Bukh district, April 1915, the result of a riot by Australian and New Zealand servicemen in Egypt (the Battle of the Wazza), partly caused by resentment at VD cases (Australian War Memorial P04752.003/Joseph McMaster)

Ruined building in Cairo’s Wagh-el-Bukh district, April 1915, the result of a riot by Australian and New Zealand servicemen in Egypt (the Battle of the Wazza), partly caused by resentment at VD cases (Australian War Memorial P04752.003/Joseph McMaster)

Chapters Five to Eight detail the tangled web of Ernest Dunbar’s life and show that his story was far from unique. There is the remarkable Maurice Buckley who, having contracted VD, was on his way back to Australia a mere month after arriving at the front. He deserted and then, as Gerald Sexton, returned to fight and went on to to win a VC. We are introduced to Albert Crozier, who changed his name to Michael Willis and successfully enlisted once the minimum height was lowered from 5’6” to 5’2”. He lived a life that lurched in fits and starts and ended in an accident deemed his own drunken fault.

We learn of Richard Waltham who, unlike others on the Wiltshire, was from a well-off, well-educated family of professionals. He had worked as a licensed surveyor, was promoted to corporal, and then disgraced as VD-infected. On his way home he met Harold Glading, a printing machinist. Both co-operated in their treatment and arrived in Australia ‘cured’. They returned to fight in Egypt, where Richard was killed in circumstances that remained obscure to his parents who persisted in the belief that he had been at Gallipoli. Harold’s peacetime life was plagued by illness. His widow’s unsuccessful quest for repatriation benefits is a tortuous tale of confusion, pride and ineptitude. How, one wonders, would metadata retention regimes cope with these men, their families and their name changes?

In the final two chapters, Dunbar turns to the reception of the news of VD in the AIF by the Australian public. Dr John Cumpston, wartime director of quarantine, had compiled the statistics. Moral crusaders, prohibitionists, the RSL and patriotic upholders of the heroic legend were outraged. Sir James Barrett reassured the public that only 13 per cent of mobilised soldiers had been infected, a rate lower than that in the general civilian public and sure evidence that his adoption of prophylaxis had been effective. In retrospect, the story of Major Conder, architect of the transformed Langwarrin, becomes one of the triumph of science and sympathy over righteous indignation.

Dunbar acknowledges that this is a multifaceted tale and he is frank as to what he has excluded. There is no analysis of why the outbreak of what Dunbar termed ‘wartime promiscuity’ occurred or why so many Australians became infected. There are clues: the first contingent arrived just before Christmas 1914 and leave was generous, as were Australian allowances. The soldiers were young. They had the time and means and the crowded cluster of brothels, bars and dance halls of the Wasa’a was nearby.

Some men were infected before they left Australia, some were infected on the way. There was no certain way of protecting oneself and the prophylactic ointments, applied as a thick film to a man’s genitals, may have offered some hope, but the mercury and silver could not have been in the long-term health interests of either the men or their partners. The vulcanised rubber condoms were not popular among the sexually active soldiers. Details provided in Appendix B regarding preventing, curing, and testing for VD are graphic and sobering.

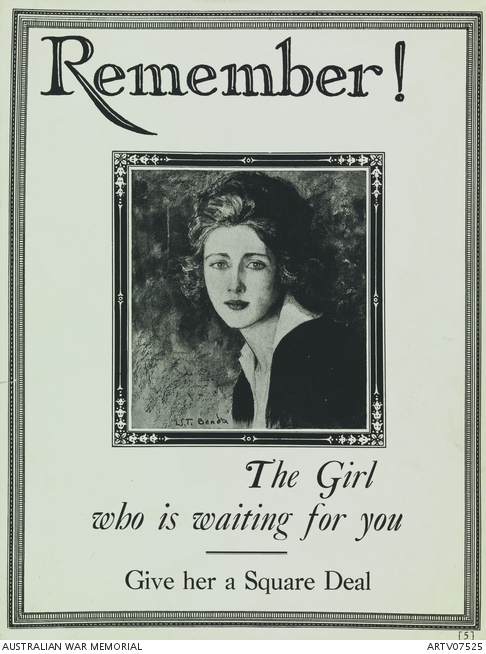

VD education poster, Social Hygiene Division, United States Army, 1918; similar campaigns for Australians seem to have been lacking (Australian War Memorial ARTV07525/WT Benda)

VD education poster, Social Hygiene Division, United States Army, 1918; similar campaigns for Australians seem to have been lacking (Australian War Memorial ARTV07525/WT Benda)

Dunbar does not delve into the legalised brothels developed by the French during the Napoleonic Wars and accepted by the British military authorities for much of the Great War. In these brothels, known as maisons tolérées, prostitutes were registered and frequently checked by doctors for signs of disease. At a practical level this regulation of the ‘sex trade’ was rationalised as an ‘outlet’ for heterosexual men, as providing ‘safer’ work conditions for the many women left without male support, and as protecting civilians from sexual assaults.[2]

Clare Makepeace has explored the multiple meanings and consequences of the varied access to and use of brothels according to rank and marital status for British soldiers. She ‘considers how warfare may have transformed heterosexual behaviour, particularly with regard to the use of amateur or professional prostitutes’.[3] Officers and enlisted men accessed different institutions: red lamps for men; blue lamps for officers. Officers were granted leave to visit prostitutes in Amiens and Paris but were disgraced if seen in public with these women. Along with married men, officers enjoyed greater privacy in the treatment of VD.

The assumptions about male sexualities embedded in these practices were riven through with class privilege, a facet of VD not probed by Dunbar. Comparative case materials put paid to the notion that promiscuity was a working-class problem. Penicillin may have replaced the toxic cocktails but sexual hierarchies remain part of military culture.

Dunbar’s story has male as ego. Women appear as ‘feminists’, family and temptresses. The long-term social and health costs to the partners and families of men who had been infected, treated and discharged are acknowledged but not explored in any detail. What of the children born to men who had been ‘cured’ by months of toxic anti-VD cocktails? What of the sexual partners who may or may not have known of the infections? What of lives lived in disgrace, denial, and disability? Dunbar says that, ‘In Australia, many children living in institutions for the blind, deaf, and disfigured had been infected before birth with the venereal disease of a parent’ (p. 8) but offers no reference.

What of the women who were infected in the brothels? What impact did the toxic paste men plastered on their penises have on the women’s health? Who were these women? Did they have children and, if so, what happened to them? I wanted to hear more of Ettie Rout, the remarkable New Zealander feminist campaigner who understood the problem was best addressed with medically-based strategies, not with moral injunctions and shaming, but whose contribution to stemming the tide of infections was erased by the guardians of national honour.

Dunbar tells us Rout’s story has already been covered elsewhere by Jane Tolerton[4] and he focuses on Rout’s collaborator James Barrett. Dunbar documents the tactics deployed by Barrett but says little of the collaboration between Barrett and Rout. How did they work together? This is the context for the struggle of the generation of leaders for whom loyalty to King and Country was manifest in honorable behaviour, for whom VD was a scourge visited upon those of poor character.

VD education placard, United States Army, c. 1918 (Australian War Memorial ARTV07551)

VD education placard, United States Army, c. 1918 (Australian War Memorial ARTV07551)

For Dunbar, the book is simultaneously a ‘cautionary tale’ to young men of today and a letter to his teenage self. It is a work that needed a severe edit. Frequent repetitions detract from the power of the story and possible lines of analyses. There are many stories of personal courage embedded in these war years but they are sometimes lost as Dunbar floods us with ‘facts’, such as how many were on each ship and at whose command and urging.

I am not suggesting these are not important facts but I think there could be a time line, a chart, or a graphic that could encapsulate the data and then the struggle that was generating the statistics would be clearer. This struggle is one of relevance today. Read and reflect: how much does a country at war want to know of what is being done in its name? How much should be withheld in the name of the safety of the troops on the ground? At what point does the suppression become a harm in itself? Who tells the story?

* Diane Bell is a writer, anthropologist and social justice advocate. She is Professor Emerita of Anthropology at George Washington University, DC, USA and Writer and Editor in Residence at Flinders University, South Australia. She currently lives in Canberra, Australia, where she continues as an independent scholar to work on Native Title projects and writing. She has published widely on matters of anthropology, history, law, religion, the environment, feminist theory and practice. Her award-winning books include Generations: Grandmothers, Mothers and Daughters (1987), Daughters of the Dreaming (1983/1992/2002), and Ngarrindjeri Wurruwarrin: a World that Is, Was, and Will Be (1988/2014).

[1] Peter Stanley. (2010). Bad Characters: Sex, Crime, Mutiny, Murder and the Australian Imperial Force. Pier 9: Sydney.

[2] See: John H. Arnold and Sean Brady (Eds.). (2011), What is Masculinity? Historical Dynamics from Antiquity to the Contemporary World, Palgrave Macmillan: NY, NY; Mark Harrison. (1995), ‘The British Army and the problem of venereal disease in France and Egypt in the First World War’, Medieval History, Vol 39: 133-158.

[3] Clare Makepeace. (2012). ‘Male heterosexuality and prostitution during the Great War: British soldiers’ encounters with maisons tolérées’, Cultural and Social History, Vol 9, No 1, 65-83.

[4] Jane Tolerton. (1992). Ettie: the Life of Ettie Rout, Auckland, London: Penguin.

Diane Bell replies to Raden Dunbar (see below)

In my opinion a book review should include a summary of the content, a critical reading of the strengths and weaknesses, and contextualise the work in the field to which it contributes. The reviewer is free to comment on why the book is of interest to him or her. This is format my review followed.

Yes I have an academic background and I urged the reader whomever that might be to engage with the book. I found the various cases studies compelling and said so. I acknowledged that the author was clear that in one book he could not address all aspects of VD in the Australian army in the war and I noted some further areas of interest.

I noted the book was written with ‘male as ego’, a comment I would make about most of the literature that addresses warfare, and I suggested what might have been pursued. It appears from the comments by the author that some of this material was edited out.

I am happy to acknowledge that my background reading and discussions with colleagues regarding the work of Raden Dunbar and Peter Stanley included a review by Kathy Evans in the Canberra Times (24/10/2014) in which quotations attributed to Dunbar appeared.

I thank Raden Dunbar for clarifying the chronology regarding his knowledge of and relationship to Peter Stanley and his work. I would now replace the sentence in my review where I wrote ‘Dunbar’s interest in telling this story was sparked by reading historian Peter Stanley’s account of hidden aspects of Australian Imperial Forces (AIF)’ with the following:

In his ‘Preface and Acknowledgments’ Dunbar states, ‘This is a subject that, although rarely described by historians, is so big that a single book like this one, could never adequately cover it’ (vii). Fortunately, for the reader there are other accounts such as that of historian Peter Stanley, the co-winner of the 2010/2011 Prime Minister’s Prize for Australian History. Dunbar tells us (below) that by the time Stanley’s book was published in 2010, much of his own draft manuscript was already written. In his ‘Preface and Acknowledgments’ Dunbar thanks Stanley for his ‘encouragement and help’ (ix). Below he tells us they did not meet until 2013. It is not unusual for researchers to be approaching similar bodies of materials from different perspectives at the same time. It is unusual to learn of the work of another while one’s own book is in draft and not to address that work. Stanley’s book appears in the bibliography but not in footnotes or index.

This review of the book appears to be the point of view of an academic who would have liked a treatment of the material that was both more academic and more in line with her own interests; If so, it’s understandable.

However, the review doesn’t seem to appreciate the book for what it is; rather, it is critical of what it isn’t!

The book was published for general readers, not just for academics. In the book’s preface, I explained that the subject of First World War VD infections of Australian soldiers is so big that a single book could never adequately cover it. Although I researched numerous aspects of the disease outbreak, they couldn’t all be included in a book for general readership, including some of the topics mentioned by Professor Bell in her review.

The original manuscript was over 90,000 words. To reduce its complexity, detail, and length, in accordance with the publisher’s suggestions, I had to omit a number of aspects of the story. This also included many of the numerous footnotes of the original version.

Jane Tolerton wrote a comprehensive, award-winning biography of Ettie Rout; Jane also launched my book in Melbourne last year. Given the publishing restrictions, I could not also repeat in my book what Jane had already published in hers in 1992, including all the details of Ettie Rout’s collaboration with James Barrett.

Finally, Professor Bell includes in her review a number of comments made in a long article about the book published in The Age last year, although she doesn’t acknowledge the source. One that was attributed to me in that article, which Professor Bell unwittingly includes in her review, is ‘Dunbar’s interest in telling this story was sparked by reading Bad Characters, historian Peter Stanley’s account of the hidden aspects of the Australian Imperial Forces (AIF)’.

I did not say that to The Age journalist, and Professor Bell has repeated the error. I began research for my book in 2008, when I uncovered Ernest Dunbar’s story. By the time I read Professor Stanley’s book after it was published in 2010, much of my draft manuscript was already written.

However, I very much appreciated the suggestions and help given to me by Professor Stanley when I first met him in 2013, and still do today.

Raden Dunbar