Those heroes that shed their blood

And lost their lives…

You are now lying in the soil of a friendly Country.

Therefore rest in peace.

There is no difference between the Johnnies

And the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side

Here in this country of ours…

You, the mothers,

Who sent their sons from far away countries

Wipe away your tears,

Your sons are now lying in our bosom

And are in peace

After having lost their lives on this land

They have become our sons as well

Ever since the unveiling in April 1985 of monuments at Anzac Cove in Turkey and in Anzac Parade in Canberra, a paragraph – one version of it is above – attributed to Mustafa Kemal Ataturk has been central to commemoration in Australia and, to a lesser extent, in Turkey and New Zealand. These words are reasonably well-known in other countries as well.

Ataturk memorial, Canberra (Wikipedia)

Ataturk memorial, Canberra (Wikipedia)

The provenance of the words has always been a little uncertain. Various dates (1930, 1931, 1934, 1935, 1936) have been given for when Ataturk said them. In some versions, he made a speech which included the words. Another story has him dictating the words for delivery by one of his ministers, usually named as Sukru Kaya. (We have found at least two dates for when this speech is supposed to have happened.) A persistent version, apparently unsupported by evidence, is that Ataturk wrote a letter to ‘Anzac mothers’.

Then, there are a number of versions of the words, partly because of differing translations from Turkish to English. Even in English there are two versions, one of which can be traced to a 1953 interview of Kaya in Turkish, the other growing from correspondence in 1977-78 between the semi-official Turkish Historical Society and a retired Australian soldier, Alan Campbell. The latter version – with the equal Johnnies and Mehmets words suggested by Campbell and accepted by his Turkish contact – is the one promoted during the early 1980s by the Turkish government and the one which appears on both the monuments shown here.

Some references say the words are merely ‘attributed’ to Ataturk; others are more confident. Research by Honest History and its associates has been unable to find (yet) any evidence prior to 1953 (Kaya’s recollection of an undated conversation with Ataturk) of the words being composed by Ataturk or anyone else. (Ataturk died in 1938.) Turkish language Master’s and doctoral theses merely cite Kaya’s recollection.

Honest History as a coalition is founded on the simple proposition that honest history as a concept is history robustly supported by evidence. Once we began in mid-2014 to look at the evidence supporting the ‘Ataturk words’ our doubts gradually grew about the robustness of evidence in this small but significant corner of Australian (and world) history.

Our opinions as historians and people interested in the practice of history do not preclude us recognising the comfort that the ‘Ataturk words’ have given to many people. We know that, regardless of the evidence that we produce, some people will prefer to ignore it. That is their right; there are plenty of examples in religion and custom where myth persists because it is comforting.

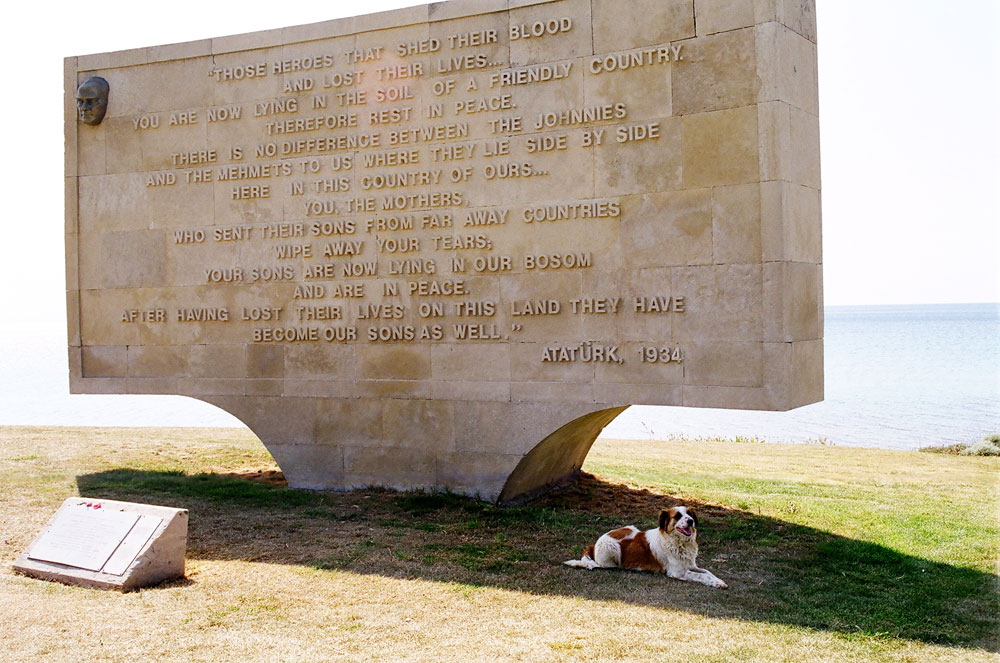

Ataturk memorial, Ari Burnu Beach (Australian Government)

Ataturk memorial, Ari Burnu Beach (Australian Government)

Some of these people have said that it ‘doesn’t matter’ whether Ataturk came up with the words. We disagree for two reasons: putting the name of Ataturk, the father of modern Turkey, under the words gives them weight that they would otherwise lack; more importantly, evidence matters and we are in the evidence ‘business’. We go where the evidence leads; that is what history is about.

We ask readers to do three things in relation to the ‘Ataturk words’. First, not to confuse comforting myth with evidence-based history; secondly, not to let wishful thinking lead to finding evidence where there is none (for example, in the greetings that Ataturk sent to a visiting British delegation in 1934, greetings which demonstrably do not include the words); and, thirdly, not to set evidentiary standards that they would not apply to themselves, particularly by demanding evidence that the words were never said anywhere (a standard which History 101 students know is impossible to attain).

The best we can do is challenge evidence that the words were said or written at particular times and ask others to provide evidence to the contrary. It really isn’t good enough for those confronted with evidence that the words could not have been said or written on a particular date in, say, 1934, to say ‘it must have been in 1935 or 1936’. They need to provide the evidence; to do otherwise is, again, to confuse wishful thinking for the practice of history.

Finally, while our work has been greatly assisted by Turkish colleagues, it should not need saying that we take no position in Turkish domestic politics or on issues affecting Turkish-Australians or people of other ethnicities in Australia. What all or any of these interests make of our work is up to them.

So far we have just summarised the issues in general terms. Now for some evidence. The links below are arranged with the most recent material first. Readers who wish to trace the story as it has developed should start at the bottom and work up. In each case, there is a sentence or two on what the item includes and sometimes a hint on how it relates to other material in the collection.

A couple of the items are only indirectly about the ‘Ataturk words’; they are all about the use of evidence. There is a lot of material here to absorb and there will be more. Honest History does not apologise for that; spending time and effort on absorbing evidence is surely preferable to the perpetuation of myth. Isn’t it?

To finish, Honest History has said many times that the words commencing ‘Those heroes that shed their blood …’ contain admirable sentiments. Remarks about settling issues between nations without the spilling of blood are much more admirable, though. For example, there are some other Ataturk words: ‘Yurtta sulh, cihanda sulh’ (‘Peace at home, peace abroad’). Those words are worth repeating.

______________________________

The Atatürk memorial at Anzac Cove has been restored but the words – though moving – are still dubious

The outcome of the refurbishment process mentioned below 16-18 June: the historically insupportable Atatürk words commencing ‘Those heroes’ reappear at Anzac Cove.

From Turkification to Islamisation: Turks and the history of the Gallipoli campaign (25 July 2017)

Ayhan Aktar from Istanbul Bilgi University takes a historical view of how Turks – with some help from non-Turks – have constructed and reconstructed the history of Gallipoli and of Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk).

Damage to the Atatürk Memorial at Gallipoli: what will happen next? (16-18 June 2017)

Our post has before and after pictures. Paul Daley in Guardian Australia wonders if Turkish Islamism is to blame. The official version is that ‘renovation’ or ‘refurbishment’ is planned. Hundreds of comments on the Guardian article. Watch this space. We offer some options for what happens next.

The Honest History Book and Atatürk (27 April 2017)

Chapter 7 of The Honest History Book is ‘Myth and history: The persistent “Atatürk words”‘, by David Stephens and Burçin Çakır; edited version published in Fairfax as ‘”Johnnies and Mehmets”: Kemal Ataturk’s “quote” is an Anzac confidence trick’ (24 April 2017).

A second Atatürk memorial in Wellington, New Zealand, gives these dubious words more currency in the Land of the Long White Cloud (25 March 2017)

(NewsHub)

(NewsHub)

We link to a couple of recent articles regarding the unveiling of a new Atatürk memorial in Pukeahu Memorial Park. New Zealand journalist, Tony Wright, uses the word ‘fraud’ to describe this latest example of Atatürkery. Honest History itself suggested to the New Zealand minister involved that she needed to do some research on provenance. There is also a note here about the history of the original 1990 Atatürk memorial just outside Wellington; political and trade issues were just as prevalent there as they were in Australia five years earlier.

Turks did the heavy lifting: a longer look at the story of the Atatürk Memorial, Canberra, 1984-85 (October 2016): Part I; Part II

Two articles on the building of this memorial revise and extend an article published in April 2016 and based mainly on the files of the then National Capital Development Commission. Most of what was in the earlier article appears here also but these two articles draw upon new sources, particularly the recollections of some people who were involved on the Australian side and, secondly, a long article in Turkish, based upon the archives of the Turkish Embassy in Australia during 1984-85.

Part I traces the development in 1984 of the deal whereby part of Turkey was renamed Anzac Cove in exchange for Australian concessions. It contrasts the committed approach of the Turkish side with a rather haphazard approach in Australia. Part II tracks the completion of the process, due to hard driving by the Turks and a late rush from the Australian side. The evidence is that the Turks at one point considered footing the bill for the Ataturk Memorial in Canberra. The article concludes that the building of the Memorial (and the matching one at Ari Burnu in Turkey) was just as much to do with Turkish foreign policy as with commemoration. The ‘Ataturk words’ played their part.

How some Turks would rather that Johnnies and Mehmets were not equal; how the Ataturk memorial came to Anzac Parade, Canberra, 1984-85 – a Turkish view (July 2016)

Two articles on the politics behind some imaginative rendering of words allegedly uttered by or on behalf of Ataturk and, secondly, on how Australia and Turkey struck a deal for some reciprocal commemoration.

Australian pilgrimages to Gallipoli in 1960 and 1965; how the Ataturk memorial came to Anzac Parade, Canberra, 1984-85 (April 2016)

Our Anzac updates reported some research on two instances where the alleged ‘Ataturk words’ were recited by Turkish officials to Australian visitors to Gallipoli. In the 1960 case, this research filled a gap that Honest History had noticed previously.

The other piece uses National Capital Development Commission files to tell the story of how the Ataturk memorial came to Canberra. The files suggest that most of the impetus came from Turkey, though Honest History is still researching.

Martyrs’ Day and what probably did not happen on 18 March 1934 (March 2016)

Cengiz Ozakinci, Honest History’s Turkish associate, and David Stephens look at the evidence for Sukru Kaya making a speech at Canakkale on 18 March 1934 including the words attributed to Mustafa Kemal (Ataturk) and commencing ‘Those heroes that shed their blood …’. They find the evidence lacking.

Tale of the Anzacs who took Mustafa Kemal prisoner in 1918 (January 2016)

More from Honest History’s Turkish associate, Cengiz Ozakinci, in Ankara, this time presenting evidence on both sides regarding an alleged incident in Syria in October 1918 involving Ataturk, his sword, a train, Sir Harry Chauvel and his staff officer.

No sign of Ataturk’s minister at Anzac, April-May 1934 (December 2015)

David Stephens analyses the most recent research from Turkish writer Cengiz Ozakinci, which busts a myth that Ataturk minister Sukru Kaya gave a speech in 1934 to visiting pilgrims from the ship Duchess of Richmond. The article compares this evidence with some Australian statements about the provenance of the ‘Ataturk words’ of 1934.

How Ataturk did not meet Birdwood in 1918 (September 2015)

Turkish writer Cengiz Ozakinci busts the myth that Ataturk and British General Birdwood met in Istanbul in October 1918 and held a post mortem on the events of 25 April 1915. (Translated from Turkish.)

Talking about Turkey in the 1960s: highlights reel (August 2015)

Considers two items from the RSL papers held in the National Library of Australia: the report of the world tour led by Bill Yeo in 1960 (which does not mention a key piece of evidence relevant to the ‘Ataturk words’); a 1969 letter by Sir Alan McNicoll, Australia’s Ambassador to Turkey, which emphasises differences between the Australian and Turkish attitudes to Gallipoli.

Two more articles on the ‘Ataturk words’ of 1934 (August 2015)

Turkish writer Cengiz Ozakinci argues that Ataturk associate Sukru Kaya’s 1953 rendition of Ataturk’s alleged words was heavily influenced by Kaya’s familiarity with the legends of Ancient Greece. Ozakinci also comments on an article by translation specialist, Anthony Pym, which was critical of earlier material from Ozakinci and Honest History. Pym later amended his article. (Translated from Turkish.)

Ataturk in the City of Hume, Victoria: Honest History Factsheet (June 2015)

Describes contacts between Honest History and the City of Hume about the latter’s plans for a community collection for a plaque containing the ‘Ataturk words’.

Ataturk’s famous words of 1934 questioned: Honest History media release (April 2015)

This is a summary of the findings to that date of Turkish writer Cengiz Ozakinci, Honest History and Guardian Australia journalist Paul Daley. It summarises the arguments for questioning the provenance of the ‘Ataturk words’, pointing to timelags, an important discrepancy in dates, and the creative role of the Turkish cultural bureaucrat, Ulug Igdemir, and the Queensland veteran, Alan Campbell, in 1978.

Ataturk’s ‘Johnnies and Mehmets’ words about the Anzacs are shrouded in doubt (April 2015)

Paul Daley article in Guardian Australia which traces research by Turkish writer Cengiz Ozakinci and Honest History and concludes: Until significant, non-circumstantial evidence to the contrary arises, the consolation to Anzac mothers so widely attributed to Mustafa Kemal Ataturk in 1934 can only remain historically dubious. It is testimony to the potency of Anzac mythology that it hasn’t been more fully tested until now.

Tracking Ataturk: Honest History research note (April 2015)

This lengthy article includes

- links to two articles in Turkish by Cengiz Ozakinci;

- links to translations of these articles provided by Mr Ozakinci;

- 19 other relevant sources with commentary; and

- examples of Australian recognition of the ‘Ataturk words’.