‘Turks did the heavy lifting: a longer look at the building of the Atatürk Memorial in Anzac Parade, Canberra, 1984-85: Part II’, Honest History, 25 October 2016 updated

This is a revised and extended version of an article published in April 2016 and based mainly on the files of the then National Capital Development Commission (NCDC). Most of what was in the earlier article appears here also but this longer article draws upon new sources and makes revisions accordingly.[1] Translations by Dr Burçin Çakır, Glasgow Caledonian University. The article is in two parts; the first part is here.

Agreement between Australia and Turkey is finally reached – or is it?

At the election on 1 December, the Hawke Government was returned, despite a small swing against it and the loss of a few seats. The election campaign had diverted Australian officials from many projects, including the Anzac Cove renaming and related matters. As we noted in a companion article, Turkish Ambassador to Australia, Faruk Şahinbaş, became frustrated around this time by the delays on the Australian side in coming to an agreement on the deal for reciprocal renaming and memorial-building.

By March 1985, however, the deal was almost nailed down. Şahinbaş felt able to take umbrage at the heavy-handed satire of Canberra Times columnist, Alan Fitzgerald, who suggested the Atatürk precedent might lead to other former enemies of the Queen demanding memorials in Canberra.[2] (There had been similar concerns in Turkey about what Pandora’s boxes might be opened by the Anzac Cove renaming: see Part I.)

Şahinbaş (Turkish Embassy, Canberra)

Şahinbaş (Turkish Embassy, Canberra)

Fitzgerald’s piece had followed an article by Frank Cranston noting that the renaming deal was moving towards completion and concrete expression. Şahinbaş responded to Fitzgerald’s outburst by sending him a copy of Uluğ İğdemir’s 1978 booklet Ataturk ve Anzaklar (Ataturk and the Anzacs) and drawing his attention to Atatürk’s (reputed) words of 1934.

Despite the scepticism of people like Fitzgerald, Şahinbaş’s assiduous work was paying off. What had happened during the summer of 1984-85 to get to this point? Official Canberra seemed by November 1984 to have accepted the ‘stone with plaque and inscription’ Atatürk Memorial option, though it was still unclear where the stone would go on the War Memorial grounds or across the road between Fairbairn Avenue and Creswell Street. One of those involved on the Australian side recalls that a monument or memorial of some sort had always been seen as the principal reciprocal gesture, even if the size and shape of the monument changed over the period of negotiation. However, other evidence suggests the Australians did not finalise the package until late January 1985.

An important piece of evidence here is a note for file by the then National Secretary of the Returned and Services League (RSL), Ian Gollings, recording contact with Giff Jones and Margaret Fanning of Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C).[3] The note is undated but its placement in the (rather untidy) RSL files suggests it dates from late January 1985. According to the note, Jones advised Gollings that the Turks had agreed to the Anzac Cove renaming and that there would be a ceremony there on Anzac Day 1985. Australia would be reciprocating with the Albany, Western Australia, and Lake Burley Griffin renaming and was to ‘[n]ame the area near the AWM as Ataturk Gardens’. A senior Turkish official would come to Australia and there would be a ceremony in Canberra on Anzac Day ‘when a plaque will be unveiled in the area of the Ataturk Gardens’.

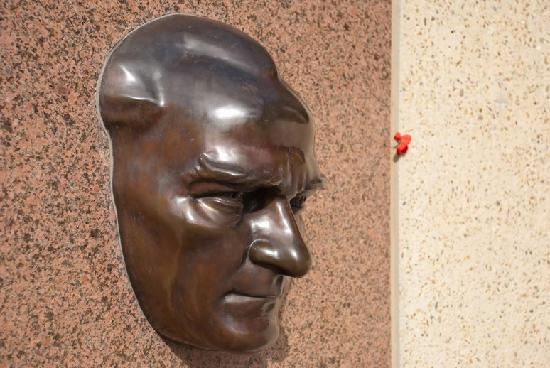

There was no mention in Gollings’ note of the plaque being attached to a monument or even a stone but other evidence suggests the Australian side were committed to something like this around this time. Şimşir’s detailed account (using the files of the Turkish Embassy in Canberra) records that Ambassador Şahinbaş met John Bowan of the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) on 22 January to discuss a proposal from the Australian Embassy in Ankara, following that Embassy’s discussions with the Turkish government. The proposal was that Turkey would provide a brass plaque bearing a depiction of Atatürk’s head and the text in English of his reputed words. The memorial would be placed on the Fairbairn Avenue-Creswell Street site, to be designated as ‘Kemal Atatürk Memorial Garden’.[4]

The head in place (Trip Advisor)

The head in place (Trip Advisor)

On 25 January 1985, Bowan wrote to Şahinbaş confirming their discussions. The mention of the Atatürk head is important: this seems to be the first time Australia came close to Turkish General Üruğ’s specifications of May-June 1984. Şahinbaş was clearly pleased, as he reported to Ankara that Australia was prepared to ‘give the name of the great Atatürk to the two most exclusive places of the federal capital’, at both ends of Anzac Parade (‘the most prominent avenue in Canberra’, as Şimşir described it) – the Memorial Garden and a section of Lake Burley Griffin – as well as to the stretch of water in Albany. The Atatürk Memorial, Şahinbaş said, would be ‘a concrete and permanent work of art that will continuously remind us of the friendship of the Turkish nation and the Australian nation’.[5]

The Foreign Ministry in Ankara responded quickly and positively:

It is essential that the monument to be erected in the Atatürk Memorial Garden by the Australian government (including the name of the great Atatürk) be built properly. The Atatürk relief profile to be placed on the monument will be sculpted in Turkey. Thus, we need to know roughly the size and shape of the monument to determine the proportions [of the relief]. We also expect that a monument with an inscription bearing Turkish and English versions of Atatürk’s statements about the Anzacs and a relief profile of Atatürk will be erected at Anzac Cove at Gallipoli.[6]

The final push – with an unexpected twist

Timing now became an issue and the timeframes were tight indeed. On 5 February, Giff Jones of PM&C advised RG Gallagher of the Department of Territories and Local Government (DTLG) that the Prime Minister wanted ‘the plaque’ in place by Anzac Day.[7] The next day, the same message came to NCDC Commissioner, Tony Powell, from DTLG secretary, John Enfield: the Prime Minister’s ‘personal interest’ dictated haste.[8]

A week later, on 15 February, the Prime Minister himself wrote to Gordon Scholes, the new Minister for Territories, asking Scholes to take ‘personal responsibility’ for the project.[9] As to what the project was, the letter referred to ‘a memorial plaque to Atatürk and surrounding garden’. There was nothing explicitly about a bas relief head though that could have been comprehended by the word ‘plaque’. (This seems to be what Bowan and Şahinbaş had in mind three weeks earlier.)

The evidence around this period, however, suggests there was still some uncertainty as to exactly what was in train. Hawke told Scholes that the NCDC thought the Fairbairn Avenue-Creswell Street site might create a traffic hazard as people crossed Fairbairn Avenue from the War Memorial but the site would have to do. (Many years later, there is a pedestrian crossing there.) Other sites had been tried out on the Turks – for example, the shore of the lake – but discussions with Şahinbaş had made it ‘clear that the Turkish Government places considerable store on the fact that the location proposed to them is in the general region of the War Memorial and Anzac Parade’.[10] (This proximity is a consistent theme in Şahinbaş’s cables to Ankara.)

It is worth noting, too, the anticipated consequences of giving the Turks a site other than near the War Memorial. The Prime Minister told Scholes that Şahinbaş had stressed ‘that any change would place the arrangements that have been negotiated in doubt’. In other words: no site near the Memorial, no Anzac Cove renaming.

Hawke also told Scholes that the Australian War Memorial had vetoed any recognition of Atatürk within the grounds of the Memorial, perhaps next to the Lone Pine, because of its policy ‘not to name features after individuals’. However, a letter from Jim Flemming, Director of the Memorial, to Tony Powell of the NCDC said the objection was that Atatürk was not Australian.[11] Despite discrepancies on the Australian side over such points the word was still ‘full steam ahead’. ‘I cannot emphasise too highly’, Hawke told Scholes, ‘that no effort must be spared to ensure the successful completion of these arrangements in time for the ceremonies on 25 April’.

There was to be more dickering – and a degree of disappointment for Şahinbaş. Around this time, Hawke met Şahinbaş, who would have passed on the recent Ankara response and his own pleasure at progress. Now the Prime Minister told Şahinbaş that one Canberra memorial to Atatürk was enough.[12] This was despite Hawke’s letter to Scholes stating that there had been agreement with the Turks that ‘part of the northern foreshore of Lake Burley Griffin will be named after Ataturk’. Thus a section of Lake Burley Griffin is to this day known as ‘Gallipoli Reach’ rather than ‘Atatürk Reach’; Şahinbaş did not achieve his ‘Atatürk at both ends of Anzac Parade’ vision, after all.

Scholes (Wikipedia)

Scholes (Wikipedia)

The action now moved to the NCDC. The NCDC files on the final stages of the Atatürk Memorial saga are a little disorganised but they disclose concerns about delays, strike action and a strong feeling that the Prime Minister’s wishes about Anzac Day could not be met. There were also some turf issues between DTLG and NCDC. The Turks remained centrally involved.

An NCDC note for file – undated but some time in March – mentions strikes in Canberra affecting the landscaping works for the memorial garden. Of more concern, though, were the delays in the delivery from Ankara of the bas relief head of Atatürk. PM&C, however, were disinclined to press Şahinbaş.[13] (What we now know from the Turkish Embassy files, via Şimşir’s article, suggests Şahinbaş would not have been averse to giving Ankara a nudge: he was always the main force behind the deal.)

By early April, the NCDC’s Michael Grace had seen and photographed the stone plinth being worked upon in the workshop of Melocco Brothers, Annandale.[14] His photograph shows a template of the text in place but Grace was worried about the missing head. ‘The space above the text is for ATATURK BAS-RELIEF which PM&C advise me today is “on its way”’, said Grace hopefully. ‘This is what the Turkish Ambassador has told PM&C.’

Grace had been keeping his superiors informed and his apparent concern about the deadline had affected NCDC Commissioner Powell, who hand-annotated a note from Grace:

There is no indication that PM&C have made the P.M. aware that the April 25th date is no longer achievable but perhaps that has been set aside because of the desire to now keep any opening date clear from April 24 this being a significant date for the Armenians.[15]

Was someone in Prime Minister and Cabinet trying to use the Armenian Genocide as a means of denying the Prime Minister his wish to have the tribute to Atatürk unveiled on Anzac Day, the day after the anniversary of the beginning of the Genocide? The National Archives and PM&C say there are no relevant PM&C files surviving so we are unable to further research these final hectic days from these files. Unfortunately.

Halefoğlu (Biyografi.net)

Halefoğlu (Biyografi.net)

As it turned out, despite the concerns, the Atatürk Memorial was unveiled on 25 April in the presence of the Turkish Minister for Foreign Affairs, Vahit Halefoğlu. There was tight security because of recent activity by ‘Armenian terrorist groups’. Pro- and anti-Turkish government demonstrators shouted at each other. Halefoğlu was the first Turkish Minister to visit Australia and Şimşir’s article makes clear the importance that the Turkish government placed on the visit: there was much more involved than a bas relief head on a plinth. The same applied to Australia: Hawke told Scholes in February that the unveilings in Canberra and Turkey on 25 April ‘will be a most important and symbolic event for Australia and for Turkey’. (More on that in a moment.)

Did anyone check that the words were Atatürk’s or was it not an issue?

Neither the Turkish or the Australian side questioned whether the words used on both the Anzac Parade and Ari Burnu memorials were actually Atatürk’s although the Turkish side at least knew there were two different versions of the words and ensured that the version that proclaimed ‘no difference between the Johnnies and Mehmets’ prevailed. If any of the Turks knew of the Gallipoli veteran Alan Campbell’s role in embroidering the words they kept it quiet in the interests of Turkish-Australian relations. After all, as Şahinbaş told his superiors, the Campbell-doctored version was the one that had become accepted in Australia.

Nor do we know whether anyone in Canberra knew that the key clause in the translation of Atatürk’s words had been produced by the Australian, Campbell, working with Uluğ İğdemir of the Turkish Historical Society, and had been available in English in this version since the publication of İğdemir’s Ataturk ve Anzaklar (Ataturk and the Anzacs) in 1978. We noted above that Şahinbaş had sent this booklet to the cheeky journalist Fitzgerald and in 1981 Ergün Pelit, Counsellor at the Turkish Embassy, had pressed it on the sympathetic journalist, Frank Cranston.

If İğdemir’s work had become the Turks’ favourite handout, Campbell, the central figure in İğdemir’s story, was remarkably inconspicuous in the story of the Anzac Parade memorial. Nowhere in Simsir’s long article does Campbell’s name appear; nor do the NCDC files mention him or İğdemir. None of the Australians involved at the time and questioned many years later can recall Campbell’s name either, though İğdemir’s booklet is clear as to Campbell’s role: İğdemir dedicates the booklet to Campbell and Campbell’s portrait is on page 1.

Apart from his imaginative contribution to the Atatürk words, Campbell was an example of a particular type of Australian Great War veteran, the man who had a soft spot for Turkey. While 1980s official Australia might not have given a high priority to relations with Turkey, some Australians felt warmly towards the old enemy.[16] This probably facilitated the reception and consolidation of the poignant ‘Atatürk words’ beyond official Canberra.

Did this mean though that everyone accepted the words as genuine? The NCDC files hint at a lack of attention to whether the words to go on the memorial were really Atatürk’s and, as the compressed timeline spooled out, a slide towards assuming they were his. Perhaps those involved took the view that has been taken since (including by some historians) that the words were so memorable that their provenance did not matter or, on the other hand, that such great words just had to come from a great man. Or perhaps these officers were just pushed for time.

It is much more likely, however, that the question of the words’ authenticity never arose. Some Australians involved at the time certainly do not remember any question being raised as to whether the words were genuinely Atatürk’s. They took the words on trust; they had no reason to believe they were not authentic. Şimşir’s account also records no misgivings on the Turkish side. Turks might have disagreed over how Atatürk’s words should be translated – with or without the Campbell-İğdemir gloss – but they had no doubt that Atatürk had said something memorable about enemies lying dead and equal side by side.

Campbell ( from İğdemir, page 1)

Campbell ( from İğdemir, page 1)

On 31 January 1985, the Australian Embassy in Ankara sent a cable to PM&C: ‘We have seen the proposed text and consider it a satisfactory version of Atatürk’s saying’.[17] There is no indication of what checking the Embassy undertook – there was almost certainly none – but the words the Embassy had seen presumably came from the Turkish government, given that John Bowan in the PMO a few days earlier had referred to text being supplied by the Turks. While the words included Campbell’s clause they were clearly now ‘owned’ by Ankara.

The next day in Canberra, Gallagher of DTLG was perhaps a little more cautious than the Ankara Embassy officer, referring to ‘the saying attributed to Atatürk’ (emphasis added).[18] Three weeks later, Michael Grace at the NCDC had heard from PM&C that the text had arrived from Ankara.[19] He described it as ‘a quotation attributed to Kamal [sic] Atatürk dictated by PM&C officers over the phone 19 February 1985’ (emphasis added). When Commissioner Powell sent the memorial plans to Sir Anthony Synnot, Chair of the Australian War Memorial Council, he also said ‘attributed to Atatürk’ (emphasis added).[20]

If the use of the word ‘attributed’ indicated some caution at the NCDC this attitude did not survive further iterations. The Commission’s media release included this sentence: ‘This tribute was written by Atatürk in 1934 in connection with the anniversary of the Gallipoli battles’.[21] The note from Giff Jones at PM&C a week later said, ‘The words inscribed on the Memorial are Atatürk’s tribute to those Anzacs who did not return from Gallipoli’.[22] Nothing about attribution, no caution, no questions. Simple. When the Australian Acting Minister for Veterans’ Affairs, Gordon Scholes, spoke on Anzac Day, as the Memorial was unveiled, he said, ‘The inscription on the memorial is Atatürk’s own moving tribute to those Anzacs who did not return from Gallipoli’.

The main objective from the Australians’ point of view was the renaming of Anzac Cove and the nailing down of whatever quids pro quo this objective required. The authenticity or otherwise of Atatürk’s words was not considered – and there is no evidence that anyone thought the provenance of the words needed checking.

Why all this mattered more to the Turks than it did to the Australians – to the extent that Ankara considered paying for the Canberra memorial

One sentence stands out from the NCDC files. On 19 February 1985, Michael Grace of the Commission recorded a conversation with Margaret Fanning at PM&C: ‘She confirmed that the Turkish Ambassador is adamant that his Government provide the plaque(s) for this Memorial’ (emphasis added).[23]

The reference to ‘plaque(s)’ presumably means the bas relief of the head but it could also include the template which Grace observed in Melocco Brothers workshop and which was apparently used when engraving the words onto the stone. (The NCDC files show the text of the words had been available in Canberra for some time but that it had come from Ankara.[24])

Either way, the contemporary word ‘adamant’ is interesting as an indication of the anxiety of the Turkish government to control the process. Şimşir’s article, using the Turkish Embassy files from early February 1985, shows that Ambassador Şahinbaş even discussed with the foreign ministry in Ankara the possibility of Turkey paying not just for the Anzac Cove monument but for the Canberra one as well.[25]

Şimşir, May 2016 (Wikipedia)

Şimşir, May 2016 (Wikipedia)

Ankara told Şahinbaş on 5 February that it preferred that Australia pay for the Canberra memorial and Turkey for the one at Ari Burnu – this would be ‘a sign of mutual cooperation and friendship’ – but if Australia did not want to pay for the Canberra memorial, Turkey would: ‘Otherwise’ said the foreign affairs ministry, that is, if Australia was reluctant, ‘the costs will be borne by us.’ (Aksi takdirde masraflar tarafımızdan karşılanacaktır.)

That Turkey considered paying for the Anzac Parade memorial indicates the degree of frustration Şahinbaş – and Ankara – felt at the slow pace of the Australian response. Hawke’s letter to Scholes of 15 February, however, and the Hawke-Şahinbaş meeting around this time indicates the Australian side was finally picking up the pace; Şahinbaş may no longer have felt the need to pursue the financing proposal. At any rate, Şahinbaş was able to report to Ankara on 28 February that Australia would not expect Turkey to pay for the Canberra memorial. There is no evidence that Turkey had actually raised with the Australian side the possibility of Turkey paying. (UPDATE 26 October 2016: The then Commissioner of the NCDC, Tony Powell, has advised Honest History that the complete works were paid for from the NCDC’s budget.)

The payment question aside, it seems clear that most of the heavy lifting was done by Turks right from the moments in mid-1984 when Ambassador Şahinbaş started to calculate what degree of revised Australian nomenclature would suffice to honour Atatürk and General Üruğ intervened and decided that a monument was indispensable. On the other hand, there is considerable evidence that – with the exception of a couple of action officers in the NCDC – Australian official attention to what was happening was intermittent, superficial and confused. In a busy, fairly new government, building a monument on Anzac Parade was not a priority issue, except insofar as it involved delivering on a prime ministerial undertaking about the Anzac Cove renaming.

Why were the Turks so keen though? Turkish political and diplomatic motives were crucial in 1984-85. The Turkish coup of 1980 had ended years of instability in the country yet left Turkey seeking to shore up its Western networks. Ambassador Şahinbaş regularly told his superiors in Ankara that the renaming deal would enhance Turkey’s standing in Australia, a small but significant Western nation. As we noted earlier, the visit of foreign minister Halefoğlu was seen as significant in building relations with Australia – and, by extension, with the West as a whole. The minister stressed Turkey’s important role in the Western world and, in the Middle East, its geostrategic importance to the Iran-Iraq conflict and the situation in Lebanon. He and his Australian counterpart, Bill Hayden, welcomed the further development of friendly relations between their countries.[26]

Even more than it was reaching out to the West, though, the 1980 junta was reaching back to Atatürk.[27] One of its first acts was to revive the early Republican Kemalist doctrine. Only Kemalism (Atatürkçülük) could foster national unity and modernity to reach the level of Western nations, bring the divided nation together after instability in the 1970s, and restore the authority of the state. The regime launched a massive campaign with Kemalist books and educational materials, streets, roads, buildings and airports named or renamed after Atatürk, Atatürk’s portrait on mountainsides and in classrooms, offices, homes and public places.

The Gallipoli story was central to this period and rhetoric about it addressed both national and international audiences; Atatürk, his military reputation boosted ex post facto by the new Turkish republic with the help of his former enemies, was inextricably linked to Gallipoli and thus to the Anzac countries.[28] New history textbooks from the Ministry of Education stressed the bravery of Turkish soldiers, the leadership of Atatürk and the ideals that Turks should adopt from this period of their history. Gallipoli also was becoming an important tourist destination, of great interest to the Turkish government in that regard.

Most importantly, the new Turkish Constitution of 1982 was built around an idealised image of Atatürk. The preamble of this document referred to ‘the concept of nationalism introduced by the founder of the Republic of Turkey, Atatürk, the immortal leader and the unrivalled hero, and his reforms and principles’. İğdemir’s Turkish Historical Society had become a government body in August 1983. Under Article 134 of the Constitution, Turkish cultural institutions, including the Society, were tasked ‘to disseminate information on the thought, principles and reforms of Atatürk, Turkish culture, Turkish history and the Turkish language’. (In 2016, there are moves to wind back these provisions.)

The ‘Atatürk words’ commencing ‘Those heroes that shed their blood …’ were redolent of compassion and forgiveness. They presented an attractive image of the Great Leader that was still relevant 50 years on from when he was alleged to have said them and 70 years on from Gallipoli. Kemalist military men like President Evren and General Üruğ and diplomats like Şahinbaş were committing to promoting the Atatürk legacy at home and abroad to benefit the Turkish state.

Abroad, at a time when Turkish relations with Western countries were patchy (poor with Europe, reasonable with Reagan’s America), there was a strong incentive to use the ‘Atatürk words’ to support diplomacy with an American and British ally in the Southern Hemisphere. The ‘Atatürk words’ – and the monuments in Canberra and Turkey on which they were inscribed – were just as much about Turkish foreign policy (to which Australia responded) as they were about commemoration. (Commentators in 2016 noted that Atatürk’s legacy had been ‘a key reference for [Turkey’s] historically close ties to Western democracies’.)

Conclusion

Turkish efforts in 1984-85 found a ready market in an Australia that was, after a lull of some decades, becoming more interested in the events of 1915 and had a prime minister who appreciated the Anzac story, the story Australia shared with Turkey. The outcome was a memorial standing at the top of Anzac Parade, at the other end of which was a stretch of water that had almost become Atatürk Reach, and next to a road that might have been called Atatürk Avenue, beneath a mountain that might have been called Mount Atatürk, in a suburb that might have been called Gelibolu.

The Atatürk Memorial showed not only that Australia had succeeded in influencing the nomenclature of Turkish geography to commemorate Australians but much more that Turkey (particularly through Ambassador Şahinbaş and General Üruğ) had succeeded in planting in the middle of Canberra a conspicuous monument bearing portentous words. The Atatürk Memorial in turn symbolised the embedding of the Atatürk myth in Australia as a central pillar of the Anzac legend. This outcome was so important to the Turks that they even considered paying for the Memorial themselves.

Atatürk idealised (Ebru News)

Atatürk idealised (Ebru News)

Notes

[1] Conversations and correspondence, May-September 2016: John Bowan, former adviser to Prime Minister Hawke; Margaret Fanning, former officer of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet; Ian Gollings, former National Secretary of the Returned and Services League; Philip Peters, former Australian Ambassador to Turkey (1984-87); Bilâl N. Şimşir, ‘Kanberra’da Atatürk aniti tasarısı’ (‘The Atatürk memorial project in Canberra’), Atatürk Araştirma Merkezi Dergisi (The Journal of the Atatürk Research Center), XVII, 51, 2001, pp. 633–726.

[2] Alan Fitzgerald, ‘Gelobolu Plaza? Hitler Gardens?’, Canberra Times, 8 March 1985, p. 2; Şimşir pp 667-69.

[3] Note for file, undated, initialled by Gollings, Box 955[27], 3/1989(1), E1-15: Gallipoli Legion of Anzacs – RSL Ex-service Organisations Conference, 1981-89, RSL Papers, NLA MS 6609.

[4] Şimşir, pp. 654-56.

[5] Bowan to Şahinbaş, 25 January 1985, NCDC 84/1626/1/22; Şimşir, pp. 656-57.

[6] Şimşir, pp. 657-58.

[7] Jones to Gallagher, 5 February 1985, NCDC 84/1626/1/30.

[8] Enfield to Powell, 6 February 1985, NCDC 84/1626/1/30 (sic).

[9] Hawke to Scholes, 15 February 1985, NCDC 84/1626/1/59.

[10] Frank Cranston wrote on 2 March that ‘there was some bureaucratic opposition to the idea of changing a significant feature in the Australian capital to conform with the Government’s agreement with Turkey’. He said also that the Gallipoli Legion of Anzacs (see Part I) had proposed naming the forecourt of the new Parliament House ‘“Gallipoli Plaza’, or “Gelobulu Plaza” if the Turks prefer their version’. Cranston also recorded that Turkey ‘recently sought clarification of the Australian agreement to reciprocate with a similar gesture’. This was probably a reference to Şahinbaş keeping up the pressure on his Australian interlocutors, including Hawke.

[11] Flemming to Powell, 21 February 1985, NCDC 84/1626/1/122.

[12] Undated note for file, NCDC 84/1626/1/125.

[13] Undated note for file, NCDC 84/1626/1/166

[14] Grace to J. Mackintosh, NCDC, 5 April 1985, NCDC 85/596/1/140.

[15] Powell to M. Latham, Deputy Commissioner, NCDC, on Grace to Powell, 12 March 1985, NCDC 84/1626/1/125 (sic).

[16] See, for example: David Stephens, ‘More on the Australian pilgrimages to Gallipoli, 1960 and 1965’, Honest History, 26 April 2016.

[17] DFAT Ankara to PM&C File no. 84/0962, 31 January 1985, NCDC 84/1626/1/27.

[18] Gallagher to Grace, 1 February 1985, NCDC 84/1626/1/24.

[19] Grace, note for file, 19 February 1985, NCDC 84/1626/1/189.

[20] Powell to Synnot, 20 February 1985, NCDC 84/1626/1/70.

[21] Draft media release, 18 March 1985, NCDC 84/1626/1/129.

[22] Jones to NCDC, 26 March 1985, NCDC 84/1626/1/162.

[23] Grace, note for file, 19 February 1985, NCDC 84/1626/1/190.

[24] See notes 5 and 17 above.

[25] Şimşir, p. 661.

[26] Şimşir, pp. 698-702.

[27] General references in English relevant to the following paragraphs: Feroz Ahmad, The Making of Modern Turkey, Routledge, London & New York, 1993, ch. 9; Kerem Öktem, Angry Nation: Turkey since 1989, Zed Books, London & New York, 2011, ch. 2; Erik-jan Zürcher, Turkey: A Modern History, IB Tauris, London & New York, 2004, ch. 15.

[28] See Ayhan Aktar, ‘Mustafa Kemal at Gallipoli: the making of a saga, 1921-1932’, MJK Walsh & A Varnava, ed., Australia and the Great War: Identity, Memory and Mythology, MUP Academic, Melbourne, 2016, pp. 149–71. Aktar describes how Charles Bean, his British war historian counterpart, CF Aspinall-Oglander, and Winston Churchill cooperated to build up the then Mustafa Kemal’s military reputation in the 1920s: it was easier to justify defeat at Gallipoli if it could be shown there had been a ‘man of destiny’ calling the shots on the Ottoman side. The new Turkish regime took up the theme with alacrity. By the 1930s there were also diplomatic imperatives, as Britain cultivated President Atatürk.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.