‘Anzac and Anzackery: speech to Kogarah Historical Society, 14 May 2015′, Honest History, 9 June 2015

I acknowledge the Gadigal People of the Eora Nation, the traditional custodians of this land, and their elders past and present. I want to start by showing you an extract from a letter.

We have seen enough and lost enough to realise what a horrible, disgraceful thing war is. Sometimes when one sees some fine young chap with a ghastly wound one wonders whether any quarrel between any nations is worth bothering over to the extent of killing even one human being … What awful foolishness it seems, and the individual only counts as an instrument to direct and pull the trigger of a rifle or some other machine.

That letter was written at Gallipoli on 1 July 1915. Now here is an extract from another document.

On 25 April 1915 a new world was born. A new side of man’s character was revealed. The Spirit of ANZAC was kindled. It flared with a previously unknown, almost superhuman strength. There was a determination, a zest, a drive which swept up from the beaches on Gallipoli Peninsula as the ANZACs thrust forward with their torch of freedom. As they fell, they threw the torch to those following so their quest would maintain its momentum.

That Torch of Freedom has continually been thrown from falling hands, has kindled in the catchers’ souls a zeal and desire for both our individual liberty and our country’s liberty. That desire has been handed down with the memory and burns as brightly as the flame which first kindled it.

Those words were written in Brisbane in the 1980s.

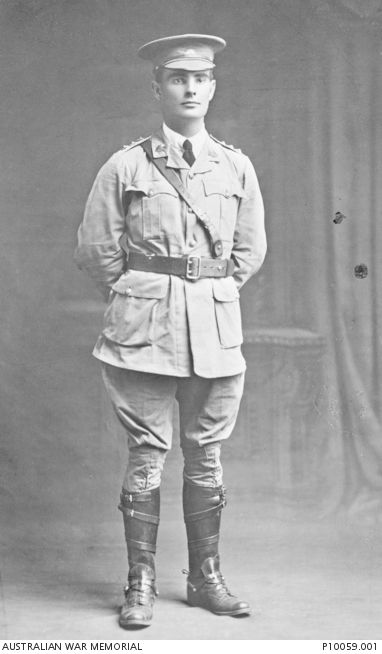

Captain Syd Campbell, 8th Light Horse (Australian War Memorial P10059.001)

Captain Syd Campbell, 8th Light Horse (Australian War Memorial P10059.001)

The letter I showed you first was written by my great-uncle, Captain Syd Campbell, of the 8th Light Horse, to his sister, Hetty. Thirteen days after Syd wrote the letter – and before Hetty read it – Syd had both legs shot off while he was swimming in Anzac Cove. He died on a hospital ship and was buried at sea.

The other extract comes from a piece called ‘The Spirit of Anzac’. It was written by Colonel Arthur Burke OAM (Retired) who served in Vietnam but who was not at Gallipoli. Colonel Burke has for many years been President of the Anzac Day Commemoration Committee of Queensland.

Study in contrasts

My talk today is called ‘Anzac and Anzackery’ and it contains a lot of contrasts – contrasts of the sort that emerges from those two documents that I’ve just shown you. Essentially, I want to distinguish between two types of commemoration – Anzac and Anzackery. The author Michael McGirr, writing in 2004, put the difference well, I think.

Creeping Anzacism [is] … the way in which the remembrance of war is moving from the personal to the public sphere and, with that, from a description of something unspeakable to something about which you can never say enough … [T]he commemoration of war has changed from a quiet remembrance of other people to an unrestrained endorsement of ourselves.

So, on one hand, there is commemoration that is built around individual stories like those of Syd Campbell, which are essentially, private, family stories which are poignant in an understated way, but which carry their own innate drama. On the other hand, there is the sort of shouting, overblown, jingoistic commemoration – even celebration – that is exemplified by Colonel Burke.

That second form of commemoration – the Colonel Burke style – is what our group, Honest History, and others have come to call Anzackery. We didn’t invent the term; it’s been around for nearly 50 years. It was coined by Geoffrey Serle, who served in World War II and later became a distinguished historian and wrote a biography of Sir John Monash. Geoff Serle was a no nonsense sort of guy and he would have had great fun with Colonel Arthur Burke.

Colonel Burke’s little essay is a good example of Anzackery but it is by no means the only example of the genre. Recent Australian prime ministers – both sides – have been good at it, too. Here’s something from Kevin Rudd in 2010.

For Australia, our identity has been etched deeply by what we call ANZAC. For nearly a century … ANZAC has occupied a sacred place not far from the nation’s soul. It shapes deeply our nation’s memory. It shapes deeply how we see the world. A hundred years later, it shapes too what we do in the world. Neither religious nor secular, whatever our beliefs are, ANZAC is profoundly spiritual – inspiring pilgrimages still to that far-off place where our modern-day pilgrims drink deep from the well of national memory … I believe each generation of Australians has a duty to pass this torch to the next.

Prime Minister Rudd and Therese Rein, Anzac Day, Canberra, 2009 (Zimbio/Getty Images/Mark Nolan)

Prime Minister Rudd and Therese Rein, Anzac Day, Canberra, 2009 (Zimbio/Getty Images/Mark Nolan)

The current Director of the Australian War Memorial, Dr Brendan Nelson, is good at it also. He is a master of hyperbole and Anzackery is all about hyperbole. Here is something Dr Nelson said in February this year. He was speaking at the official opening of the refurbished World War I galleries at the Memorial.

In these First World War Galleries, our nation reveals itself in the men and women whose story it tells. It is who we were and who we are. Facing new and uncertain horizons, it is also a reminder of the truths by which we live, how we relate to one another as Australians and see our place in the world … Every nation has its story. This is ours.

Story. Singular.

Now, at the other end of the lake in Canberra, the National Museum of Australia carries the slogan, ‘where our stories live’. Stories. Plural. And the Museum has been running a program about the ‘defining moments’ in Australian history. Moments; plural.

Now, I admire the vigorous marketing strategy of the War Memorial but I think the National Museum’s take on our history is a little closer to the mark. Stories rather than story. Plural rather than singular. Complex rather than simple. Lots of stories rather than one big, bloody, sentimental, maudlin story.

That broader approach certainly appeals to us at Honest History. Our motto is ‘Not only Anzac but also … also lots of other strands of Australian history’. Of course, Anzac is important, wars are important in our history, not so much because of what Australians have done in wars but because of what wars – all of our wars – have done to Australia and to Australians.

But there are many other parts of our history that are important, as well. And they are important not only as pieces of our past but for how they have shaped us today and for what we make of them in the future. That’s what Honest History is basically about.

But back to Dr Nelson. Dr Nelson also emphasises the emotional connection that he thinks we need to feel with the men and women who died in uniform. At the Senate Estimates Committee hearing earlier this year, Dr Nelson was talking about the Afghanistan exhibition at the Memorial and he said, the exhibition was ‘extraordinarily powerful’. He went on: ‘There is immense emotion revealed in that exhibition’.

Maybe so but there is very little in that Afghanistan exhibition that encourages the visitor to think about why Australians were there, what were the historical forces leading to us being there, and whether it was all worth it. So, emotional perhaps but not very useful. As my colleague – but not relation – Alan Stephens said last year, ‘when it comes to the responsibility of explaining why we went to war, and what it has meant, Afghanistan, like so many other galleries in the Australian War Memorial, misleads by omission’.

So, the emotion quotient shouldn’t be the sole or the main criterion when we look at war. I agree with Dr Nelson about the emotions that war, and particularly death in war evoke but I would also like to leave some room for reason when dealing with war and its implications. Dr Nelson has a colleague on the War Memorial Council, the author Les Carlyon, and Les Carlyon said a perceptive thing at the opening of the refurbished galleries at the Memorial back in February.

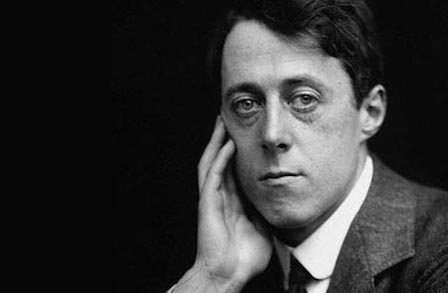

Peggy Noonan (Salon)

Peggy Noonan (Salon)

Carlyon told a story about Peggy Noonan, who was President Reagan’s speechwriter, when she was writing a speech for Reagan to make at the anniversary of D-Day (1984) and people were saying to her: ‘It’s got to be like President Lincoln’s Gettysburg address – it’s got to make people weep’. And Noonan got tired of people telling her this and eventually she said: ‘The Gettysburg address doesn’t tell you to weep – it tells you to think’.

That’s about this balance between reason and sentiment, between thought and emotion. (We will come back to that point a little later.)

Dr Nelson has also been fond of saying that ‘the soul of Australia’ can be found in the War Memorial. I’m not enough of a theologian to know whether souls can be divided but I think most Australians would like to think that our soul can be found in lots of places as well as the Memorial.

Anyway, back to Anzackery. We will see a lot of Anzackery over the next four years, particularly in this year, 2015, one hundred years since that famous invasion of the Ottoman Empire. For that reason, it seems important to know how to identify it. How to identify Anzackery. So, what I want to do now is to present a number of contrasts between Anzac – which I’ll present as the dignified commemorative ideal – and Anzackery – the bloated caricature of commemoration.

Private and public

First of all, as I’ve suggested already, Anzac should be mostly private. Anzac, the way I see it, is essentially about the private, within-family, remembrance of – and caring about – people who have suffered in war, both those who have been killed and not come home and those who have come home but who are injured in body or mind – and those who live with the memory of the dead and the reality of the presence of the living.

If we think about that famous couple of lines by Laurence Binyon – ‘they shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old’ – Anzac is really about both groups of people who go off to war, those who don’t come back – the forever young – and those who come back and grow old. And it’s also about the families of both of those groups. So, four groups altogether.

Laurence Binyon (Poetry Foundation)

Laurence Binyon (Poetry Foundation)

For families who are directly affected by war, commemoration isn’t parades and wreaths and speeches by politicians; it is something they live every day and every week – forever and down through the generations. It is the reparation that families pay for the decisions that governments make to send men and women to war.

It is, for example, the bundle of letters and newspaper clippings that I found in my mother’s belongings after her death, which showed the efforts she had made to find out what had happened to her brother, who went missing in action flying in Burma 50 years before. It is the five decades that my father and his siblings spent, not knowing the circumstances of the death of their brother after the fall of Singapore. It is the PTSD that my father and my aunt suffered – privately – from their experiences in World War II.

Anzackery, on the other hand, is public, very public. It’s marches and flags and hymns and speeches. Nowadays it’s also projections of pictures of Diggers onto buildings, it’s battlefield tours and Gallipoli cruises, it’s boys and girls on their gap year, wrapping themselves in Australian flags at Anzac Cove or getting drunk in the streets of Canakkale and shouting ‘Aussie, Aussie, Aussie, Oi, Oi, Oi’ – not knowing or caring that this ‘patriotic’ chant was pinched, with very little alteration, from Welsh rugby crowds.

It’s also a huge range of Anzac memorabilia and knick-knacks, it’s the prime minister describing the troops going off to Iraq (for the third time) as ‘the proud sons of Anzacs’. (James Brown, a former soldier, says many modern soldiers hate being compared with the Anzacs.)

It’s ministers and prime ministers and war memorial directors making emotional speeches to nostalgic audiences about the Anzac legend, it’s Anzac football matches in whatever code you fancy, and it’s 12 year-old children recording the names of dead soldiers for playing on a continuous loop in the Roll of Honour cloisters at the War Memorial. (The War Memorial says this will help these children connect with the dead.)

Anzackery is sentiment and it’s nostalgia and it’s nationalism – which people think is patriotism but which is really jingoism. Anzackery tries to make sense out of it all – out of war and its effects – to comprehend things that are not really comprehensible.

The American historian, Drew Gilpin Faust, said this about the aftermath of the American Civil War but it could apply to any war.

The war’s staggering human cost demanded a new sense of national destiny, one designed to ensure that lives had been sacrificed for appropriately lofty ends. So much suffering had to have transcendent purpose, a “sacred significance”…

1865: collecting bones after the Battle of Cold Harbor (Wikimedia Commons/Library of Congress/John Reekie)

That’s a similar sentiment to the one you see on the King’s Penny or Dead Man’s Penny that the families of the dead received after the Great War. The script around the outside reads: ‘He Died for Freedom and Honour’. No need to question what the war and the death was all about or whether it was worth it; the King has given us the answer. ‘He Died for Freedom and Honour.’

Those words may have been a great comfort to some families but they are words which are very much open to question. Questioning these comforting ideas isn’t easy, though. The young journalist, Kate Aubusson, who made the recent ABC documentary, Lest We Forget What?, said she grew up feeling it was somehow un-Australian not to go for this sort of stuff in a big way.

The American musician and social commentator, Michael Stipe, would have agreed with her. He said this: ‘More and more, what we “feel” about collective history seems like something manufactured, and kind of pumped into us, rather than a real emotion’.

The ABC presenter, James Valentine, hit the same note last month. He said: ‘I’m being told repeatedly what I should feel. Exactly how solemn I should be, which parts of the story I should mark and what lesson I should draw from them …’ I wonder if he saw the irony that the ABC, as the official Anzac broadcaster, with its platoon of presenters at Gallipoli, at the Dawn Service, on the evening news, was playing a leading role in telling him how he should feel.

Individuals and the mass

Let’s get back to the Anzac ideal. Secondly, Anzac, as I see it – the ideal – would focus on individuals, individual soldiers, individual families, individual tragedies. Earlier, I quoted Michael McGirr’s remark that Anzac commemoration had drifted away from ‘quiet remembrance’ into something noisier, much more boastful, more self-indulgent, more narcissistic.

Narcissism? This is what he said: ‘People now seem to believe that in looking at the Anzacs they are looking at themselves. They aren’t. The dead deserve more respect than to be used to make ourselves feel larger.’ That’s what he meant by narcissism.

I suggest we need to get back to quiet remembrance of individuals, to think about what war did to these individuals and to their families. We may need to do some research, to find out some details about these individuals. My friend and colleague, Peter Stanley, last year published a book, Lost Boys of Anzac, about 101 Australians who came ashore on that first Anzac Day in 1915 and who died on the same day.

Peter discovered lots of new information about these men and their families. Indeed, half of the book is about what happened afterwards, about the stories of the families, mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers, who tried to find out what had happened to their son or brother at Gallipoli. Because Gallipoli was chaotic and men died and fell in ditches and their bodies were never found. Someone’s brother, someone’s son. Both Turkish and invaders.

Peter’s key message was this: ‘They [the Lost Boys] should no longer remain as abstractions in Anzac Day addresses’. They were real people, with characters, flaws and strengths. They were not embodiments of an Anzac legend, not superheroes. In other words, they were human beings – like us.

The next example I use here might be a surprise; but it is certainly an example of individuals who died in one of Australia’s wars. We could try to find out more about the individuals who died in massacres like the Waterloo Creek and Myall Creek massacres on the Gwydir River in 1838. They were Indigenous Australians; 50 of them were killed at Waterloo Creek and 30 (unarmed) were killed at Myall Creek. Some of them were warriors, some were women and children. At Myall Creek, according to the testimony at the trial of the perpetrators, Indigenous children were beheaded with swords.

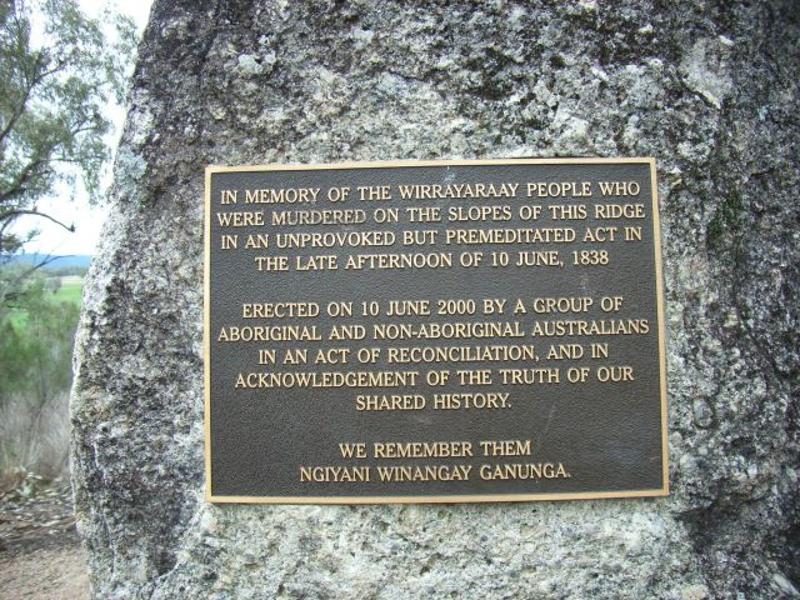

Myall Creek Massacre memorial (Baseline NSW)

Myall Creek Massacre memorial (Baseline NSW)

So victims of war are not just people in uniform. We tend not to know the names of the individual Indigenous victims although Henry Reynolds describes these wars as arguably our most important conflict. The latest research suggests that there were more than 60 000 Indigenous men, women and children killed in these wars between 1788 and 1928 – that’s 1928 – which is about the same number of Australian men in uniform as were killed in World War I.

There were many more incidents and battles and skirmishes like the ones at Myall Creek and Waterloo Creek and the one at Coniston in the Northern Territory in 1928. What’s significant about Myall Creek, though, is that it is said to be the only case – the only case in 140 years – where white settlers were tried and punished for their crimes.

Let’s look at another individual. Here’s a quote from an individual soldier of World War I.

I was at the front for thirteen months, and by the end of that time … [t]he war had become an everyday affair; life in the line a matter of routine; instead of heroes there were only victims … [T]here was no rhyme or reason in all this slaughtering and devastation; pain itself had lost its meaning; the earth was a barren waste … Most people have no imagination. If they could imagine the sufferings of others, they would not make them suffer so.

The soldier’s name was Ernst Toller. He served in the German Army in France in 1915 and 1916. Regardless of the number they are given or the uniform they wear, soldiers are individuals.

Anzackery, on the other hand, is big on numbers, it looks at the mass, not the individual. When the prime minister made a statement just before he left for the Gallipoli commemoration this year he used some well-known figures – nearly 9000 dead men – dead Australians – at Gallipoli and 18 000 wounded, and 62 000 killed throughout the war.

Public figures also often make something of the proportions; depending on how you slice it – whether you take it as a proportion of 18 to 40 year-olds or 18 to 50 year-olds – somewhere between 42 per cent and one-third of eligible Australian males enlisted. But they’re all just numbers, the more you obsess about them, the more you analyse them, the more you obscure the individual and the family stories.

There’s one big number statistic that is worth remembering, though. Marina Larsson, who wrote a book called Shattered Anzacs, about the aftermath of the Great War, makes the point that, with 62 000 dead but more than 200 000 returning home wounded and shell-shocked, there were many more families after that war living with mentally or physically damaged former soldiers than there were families dealing with the grief of bereavement.

Yet it is clear where the commemorative attention falls, even a century on. We relentlessly, repetitively commemorate the dead, yet we are only now, against considerable resistance from the Defence bureaucracy, starting to digitise the repatriation files from the Great War so that we can research the lives of those returned men through the 1920s, the 1930s and so on.

Consequences and avoidance

Thirdly, and flowing on from the previous point, Anzac, as I see it, deals with the consequences of our national decisions to go to war. As I said earlier, the reparations that families pay. When the soldiers of the Empire came home after the Armistice that ended the Great War, they were promised, or they expected, homes for heroes, land in soldier settlement programs, decent jobs so they could support their families, and no more wars, since they had just fought the war to end all wars.

Roddy family, soldier settlers, of Lacmalac, near Tumut, NSW, c. 1941 (Australian War Memorial P07129.002)

Roddy family, soldier settlers, of Lacmalac, near Tumut, NSW, c. 1941 (Australian War Memorial P07129.002)

Just reciting that list makes you realise that the consequences of that war were not dealt with particularly well. The soldier settlement program is a good example: small, remote blocks with poor soil and little water; families living in tents or shacks till they could manage to build a house; struggles to make a block pay and to pay the block off; drought; debt. More than half the soldier settlers after the Great War had walked off their blocks by 1938.

Then, Bruce Scates at Monash University has been working for some years on a project called ‘100 stories’ and some of the stories he wanted to tell about the aftermath of war were so doleful, they said so much about how men, women and children in those days after the Great War suffered from what they were going through and from our failure as a society in those days to deal with the consequences of war, they were so powerful and so damning, that the Department of Veterans’ Affairs decided to pull out of Professor Scates’s project. ‘Aren’t there any positive stories?’ That was the plaintive question that one of the public servants involved in that process put to Professor Scates. There was even a bit of a bargaining process about the proportion of good news stories that might be included to balance the horrific ones. But it didn’t get very far.

Are we are any better today at dealing with those consequences? The fact that organisations like Soldier On and Mates for Mates have had to be set up to deal with the aftermath of our more recent wars suggests we aren’t doing much better at the government level. Yet we are spending over $500 million on commemorating the centenary of Anzac and the great bulk of that money is going to projects like cleaning up the dioramas at the Australian War Memorial, refurbishing the various looming monuments in our capital cities and building new monuments in suburbs and towns, in New Zealand and on the Western Front (that one will be a multi-million boost to the economy of Northern France to build an interpretive centre – which is a sort of high tech museum).

We are very good at dealing with the consequences when the consequences are dead soldiers. We have well-honed rhetoric about ‘the fallen’, ‘making the supreme sacrifice’, ‘dying for freedom and honour’ and ‘nation-defining moments’ occurring in the midst of blood and slaughter. But we mumble and we dissemble about the living consequences.

The Australian War Memorial has many pictures of facial injuries suffered in the Great War but it prefers to keep most of these pictures locked up. We are surprised to find out – this is an exhibit at a current exhibition at the Museum of Melbourne – that one survivor from World War I spent the remaining 43 years of his life ‘living’ in a bed with wheels. Or that the last mentally deranged men from that war were still around, living in secure wards, in the 1980s.

‘They shall grow not old, age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn …’, as Laurence Binyon said. And he goes on, ‘We will remember them’. We’ve certainly remembered them – the ones who will never grow old – but we often haven’t done all that well by the men – and women – who have grown old in our midst. And some veterans of Vietnam and Iraq and Afghanistan reckon we aren’t doing well all over again.

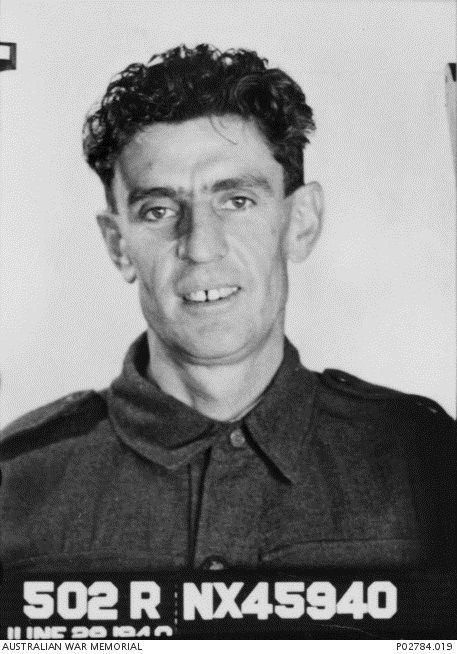

Private William Cant, 2/29 Battalion, one of 145 men massacred by Japanese, Parit Sulong, after Battle of Muar (Australian War Memorial P02784.019)

Private William Cant, 2/29 Battalion, one of 145 men massacred by Japanese, Parit Sulong, after Battle of Muar (Australian War Memorial P02784.019)

Honesty and euphemism

Fourthly, Anzac is – or should be – honest; it avoids euphemism. I’ve just touched on this point but I’ll say some more about it. When talking about men and women who die in war, Anzac – the honest approach – would say ‘dead’ or ‘killed’ rather than ‘fallen’. If it used the word ‘sacrifice’ it wouldn’t say ‘made the ultimate sacrifice’. It wouldn’t even use the active voice; it would use the passive voice as in ‘they were sacrificed’. Those euphemisms – ‘fallen’, ‘sacrifice’ ‘the glorious dead’ (the prime minister used that one last month in France) – are the essence of Anzackery.

Anzac, in the way I see it, on the other hand, wouldn’t make big claims like ‘they died for our freedom’. It would simply say ‘they died serving a government policy’ and then it would go on to question whether that policy made sense then or makes sense now. When we hear that mantra, ‘They died for our freedom’, it’s usually a sign that someone is trying to stop us asking difficult questions about what they really died for.

Anzac, as I see it, doesn’t turn soldiers into superheroes or saints, dying for grand causes. Anzackery does – or tries to. You even find euphemisms in quite sober books of military history. My uncle, Hector Charles Stephens, is listed in his battalion history as dying during guerilla operations in Malaya in 1943. Now, you may recall that the war in Malaya was pretty much over by February 1942, with the fall of Singapore. What actually happened to my uncle and about a dozen others – we found this out 50 years later – is that they were separated from their comrades after the Battle of Muar (where 300 Australians were killed in a single day) and they wandered around in the jungle for more than a year after that, most of the time without weapons, living on handouts from the local Malays (who were often on the verge of betraying them to the Japanese), and occasionally getting help from Chinese guerrillas.

What happened to them next? Gradually they killed themselves or, like my uncle, they died of disease. One of them survived and was rescued by a British submarine in 1945. (He told his story in a book and that was how we found out, 50 years on, what had happened to Uncle Hec.) So much for the euphemism, guerilla operations.

Anzac, in my view, and to say again, doesn’t have room for soldiers who are gods. It allows for human frailties and failures and fear. For knaves and villains as well as for saints. And for people who stumble around in the jungle, dying of disease, and not looking much like soldiers at all. Lots of mess and confusion and uncertainty. Just like real life.

Peter Stanley won a share of the Prime Minister’s History Prize a few years ago for a book called Bad Characters: Sex, Crime, Mutiny, Murder and the Australian Imperial Force. You heard the word ‘mutiny’: there were mutinies among Australian soldiers in France in 1918, just as there were among French soldiers. These guys had just had enough. You heard the word ‘murder’: Australian and New Zealand soldiers murdered a couple of hundred Palestinian Arab civilians at Surafend in 1918. They were retaliating for the killing of a fellow soldier; they had also had enough of war.

They are awkward facts amid the heroism and the bravery. Anzac, though, in my view, doesn’t try to suppress debate or discussion because of some sensitivity or some imagined injury to people today. Anzackery on the other hand, does try to suppress and disguise.

At Honest History, one of our favourite Anzackers is Brigadier Andrew Nikolic, federal member for Bass in Tasmania. When the ABC early last year published a piece on the launch of our Honest History website – it was a scrupulously balanced piece but it included Peter Stanley talking about the unsoldierly exploits of some Australian soldiers in the brothels of Cairo – Brigadier Nikolic accused the ABC of lacking ‘situational awareness’ for broadcasting such material in a year when we were starting to commemorate the centenary of World War I.

Another champion Anzacker is Senator Michael Ronaldson, the federal Minister for the Centenary of Anzac. (It’s his job.) In August last year, when the ABC (again) ran an item that suggested Australian soldiers in New Guinea in 1914 might have massacred some Germans and some New Guineans under German command, the Minister attacked the ABC for being ‘insensitive’ towards the surviving relatives of those Australian soldiers.

Now you can argue about timing and taste – as you could with the recent case of Scott Mcintyre of SBS – but you – or at least I – get the feeling that there is more behind the reactions of people like Nikolic and Ronaldson than simply some concerns about the niceties. My colleague, Frank Bongiorno, a historian at ANU, reminded us recently that ‘[t]here is a long history of contention over the significance and meaning of the Anzac legend’. The problem is that, if you decide that you would rather not be part of that tradition you can buy quite a lot of trouble for yourself. Professor Bongiorno continued:

To question, to criticise – to doubt – can become un-Australian … Anzac’s inclusiveness [trying to include everyone within the tradition] has been achieved at the price of a dangerous chauvinism that increasingly equates national history with military history, and national belonging with a willingness to accept the Anzac legend as Australian patriotism’s very essence.

So, if you are an Australian patriot you are expected to accept the Anzac legend. Or in Brigadier Nikolic’s terms, even if you have misgivings you need to display ‘situational awareness’. We at Honest History have translated that term – situational awareness – as ‘pipe down, pull your head in, keep your awkward opinions to yourself, while the rest of us have a good old patriotic celebration’.

Let’s move on to what I think should be another characteristic of Anzac, and that’s a preparedness to bust myths. We have a vision of Australians as iconoclasts, people who are prepared to cut down tall poppies.

Ataturk memorial, Be’er Sheva, Israel, carrying famous (but different) words (Pikiwiki/Avishai Teicher)

Ataturk memorial, Be’er Sheva, Israel, carrying famous (but different) words (Pikiwiki/Avishai Teicher)

OK, here’s a myth to consider. Some people here will be familiar with the words that are sometimes known as Ataturk’s letter to the Anzac mothers. (This is Ataturk, the father of modern Turkey, formerly Mustafa Kemal, one of the heroes on the Ottoman side at Gallipoli.) In the most familiar translation from the Turkish, Ataturk’s words go like this:

Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives … You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side here in this country of ours … You, the mothers, who sent their sons from far away countries wipe away your tears. Your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace after having lost their lives on this land.

We ran an item on our Honest History website in March and it referred to some research Peter Stanley and I had done last year which argued that there never was an Ataturk letter to the Anzac mothers. Instead, we suggested there was a speech in 1934 that Ataturk had helped write but which had been delivered by one Sukru Kaya, who was Ataturk’s Interior Minister.

This was pretty unremarkable research; a number of other people had come to a similar conclusion. We put a post on our website about this research and we tweeted a link to the post. Lo and behold, back came a tweet from a gentleman called Mustafa Armagan, a very distinguished Turkish historian, and he said, ‘But, it’s a fake!’ and he gave us a link to an article in the March edition of a leading Turkish magazine, Butun Dunya, by another distinguished Turkish writer, Cengiz Ozakinci.

To cut a long story short, we got some translations done – there was a second article in April – we exchanged a few emails and tweets with Mr Ozakinci, we began working with Paul Daley from Guardian Australia and we found, pretty much, that Ataturk’s famous words were indeed – a fake. Mr Kaya did not make a speech in 1934, including the famous words written out for him by Ataturk. Kaya did make a speech in 1931 that Ataturk helped him with but that was a very different speech, in which there was no suggestion that Johnnies – our blokes – were as good as Mehmets, their blokes. (That is the key line in the famous words.)

The words about Johnnies and Mehmets being equal were actually composed by an old Anzac, Alan Johnston Campbell, of Brisbane, who in 1978 wanted to improve the translation he had received from the Turks of some words in a Turkish guidebook dated 1969. The Turks didn’t object to the doctoring of the words, the words went onto the old Gallipoli Fountains of Honour in Roma Street in Brisbane – they were the new fountains in 1978 – and they are the words that have come down to us. So that when you look, for example, at the new Ataturk memorial in Hyde Park in Sydney, with Turkish and English words side by side, the Johnnies and Mehmets sentence in the English version is not at all an accurate translation of the equivalent Turkish sentence. (The accurate translation is ‘You are side by side, bosom to bosom with the Mehmets’. Nothing about ‘no difference between’ Johnnies and Mehmets.) And this dodgy translation has gone all round the world onto monuments, into books, into political speeches, and so on.

But where, you may ask, did the rest of the famous words come from – that is, the words other than the Johnnies and Mehmets – the ‘made in Queensland’ words? On the balance of probabilities, our research suggested that Sukru Kaya made them up – 15 years after Ataturk died – in an interview with a journalist in 1953. Kaya had been one of Ataturk’s closest associates when Ataturk was alive. He may have taken account of something he recalled Ataturk saying – though we have found no evidence of Ataturk saying anything that closely resembles the famous words.

Detail of Ataturk memorial, Canberra, with the famous words (Wikipedia)

Detail of Ataturk memorial, Canberra, with the famous words (Wikipedia)

But Kaya also had a personal score to settle in 1953 and some political motives, he was 70 years old, he had been out of public life for 15 years, he was probably in a highly emotional state, because right at that time was when they were moving Ataturk’s remains into his massive new mausoleum in Ankara. Masses of people were crying in the streets; it was the sort of adulatory atmosphere which very likely contributed to a bit of poetic licence by Kaya, Ataturk’s old comrade.

But, to repeat, we have found no evidence at all that Ataturk was involved in composing the famous words. The Ataturk words are lovely, comforting words but they are essentially the stuff of myth and legend – and Sukru Kaya’s imagination.

Just to round the story off, Kaya had a bit of a track record: as a civil servant in 1915 he was a key organiser of the Armenian genocide – he was briefly gaoled by the British after the war as an alleged war criminal but he escaped – and he was also involved in some ethnic cleansing of Kurds in the 1930s. If he was a mouthpiece for Ataturk – and it’s always possible that evidence to that effect will turn up – he was a pretty unsavoury one. The details of all that are on our website.

Context and parochialism

Fifthly, Anzac, the ideal, has context. It should allow us to recognise the suffering of other nations in war. It is not just an Australian story. It recognises our common humanity. We’ve extended the circle a bit to include Turks in the Great War but we need to bring in Germans and Austrians and Bulgarians and Japanese and Russians and Jews and Palestinians and New Zealanders and all the other soldiers of the Empire, and so on.

And all of the civilians who were affected, which is a much, much larger number than the number who pulled on a uniform. An American called Milton Leitenberg has calculated that about 231 million people were killed in wars and conflicts during the twentieth century and about 80 per cent of those were civilians.

In another direction, the Anzac ideal would allow us to consider more explicitly the society that existed before wars and the very different society and community that existed after them. The changes that wars bring about, how wars affect us as individuals, as families and as a nation. The changes that are all but ignored in, for example, the way the Australian War Memorial presents the story of World War I.

Before the Great War, for example, we were in Australia in many respects a confident, socially innovative place. A social laboratory for the world, as someone said, in labour and social policy, votes for women, and so on. Afterwards, we were, as Joan Beaumont says, a ‘broken nation’. Far from being a newly-born nation after the war – born at Gallipoli and standing on our own feet – we were, as Billy Hughes was proud to say in 1926, ‘more British than the British’.

An ideal Anzac tradition would also allow for the possibility of forgetting and moving on. The mantra, ‘Lest We Forget’, should not bind us for ever. Sometimes it is better to forget. Many, many of the men and women who actually went to war desperately tried to forget.

The obsession about remembrance has grown stronger the further away we get from the reality. It has grown stronger as the number of people who actually remember the reality of total war has got fewer and fewer.

Launceston children, Anzac Day, 2012 (ABC News)

Launceston children, Anzac Day, 2012 (ABC News)

The future

I think it is a characteristic of Anzackery that it persists, that it tries not to change. It wants us not to change. I think Anzackery builds in the possibility – even the probability – of war in the future. Minister Ronaldson, whom I mentioned before, is fond of saying that today’s children have a responsibility to carry forward the torch of remembrance. He also said in a speech last year that today’s children ‘must understand’ that the freedom they enjoy today was ‘paid for in blood’.

Encouraging our children to carry forward the torch of remembrance – as we do – only makes sense if we expect them at some time in the future to have to lay down that torch and take up weapons. The sort of future that includes war is made more likely by the way we look at past wars.

Elizabeth Samet lectures to military cadets at West Point in the United States. She had an article published last year which says a lot of important things about the way we think – or rather, the way we don’t think – about war. She writes about the old-fashioned sentimentality of the way we (Americans and you can easily extend that to Australians) talk about war, how ‘emotion … short-circuits reason’, how people become ‘exhibitionists of sentiment’ in relation to war, and, most importantly, how sentiment stops us asking hard questions about war and thus how it effectively supports jingoism – the inclination to wrap ourselves in the flag and go cheerfully off to war again.

What Samet is basically saying is that we are afraid to ask hard questions about war – was it worth it? did they die in vain? – because it will look as if we are devaluing the deaths of the men and women who fought. And that wallowing in sentiment, that not asking questions, makes it more likely that we’ll do it all again in the future.

Anzac and Anzackery. I know that the Anzac I’ve described here today is an ideal. But I think that it is an ideal worth striving for. On the other hand, I think an Australia in which Anzackery is rampant is not an Australia I want to see. I don’t believe it is an Australia that the men and women of Anzac would have wanted to see either.

Well said David, couldn’t agree more.