‘Investing our legacies’, Honest History, 16 April 2015

David Stephens reviews Griffith Review 48, ‘Enduring legacies’, edited by Julianne Schultz and Peter Cochrane

The title of this excellent collection is, at one level, obvious but, at another, full of possibilities. A legacy, in common parlance, is something left to you. It can pay for the renovations or for a trip to South America or it can stand in the corner and gather dust. In information technology, a legacy system is one that we would love to turn off but dare not in case it contains something useful. (Legacy, as a proper noun, is an organisation whose good works will benefit from receiving part of a $1 million donation from Carlton and United Breweries for its Raise a Glass campaign – that amount being a grand 0.004 per cent of the revenues of CUB’s parent company.)

The legacies in this volume are those flowing from the wars of the twentieth century, from the Second Boer War to Afghanistan, ‘the responses, realignments and decisions’ that came after them. Editor Schultz notes that 2015 is an anniversary of Gallipoli, VP Day 1945 and the end of the Vietnam War in 1975. ‘This is a good time’, she says, ‘to reflect not only on the actions of those wars, but on their consequences and enduring legacies’.

The legacies in this volume are those flowing from the wars of the twentieth century, from the Second Boer War to Afghanistan, ‘the responses, realignments and decisions’ that came after them. Editor Schultz notes that 2015 is an anniversary of Gallipoli, VP Day 1945 and the end of the Vietnam War in 1975. ‘This is a good time’, she says, ‘to reflect not only on the actions of those wars, but on their consequences and enduring legacies’.

The pieces in the volume are divided into 21 ‘essays’ and nine ‘memoirs’, though this distinction seems a little arbitrary. There is also a short story from New Zealander Craig Cliff, a haunting poem from Laura Jan Shore and a portfolio of art works from the prisoner-of-war days of the late Ray Parkin. The volume is well-produced on non-shiny paper (an advantage) and this reviewer found only one error. One of Ben Quilty’s paintings is on the cover.

Among the essays, Peter Cochrane notes that ‘never has the Anzac tradition been more popular and yet never have its defenders been more chauvinistic, bellicose and intolerant of other viewpoints’. Cochrane looks at the reasons for the Anzac resurgence and quotes Frank Bongiorno with approval:

There is a long history of contention over the significance and meaning of the Anzac legend. But once a tradition is defined in more inclusive terms, those who refuse to participate can readily be represented as beyond the pale. To question, to criticise – to doubt – can become un-Australian … Anzac’s inclusiveness has been achieved at the price of a dangerous chauvinism that increasingly equates national history with military history, and national belonging with a willingness to accept the Anzac legend as Australian patriotism’s very essence.

Marina Larsson makes the crucial point that the number of Australian families after the Great War ‘left to support those disabled by the conflict was markedly greater than those who mourned the “fallen”’. Larsson welcomes the opening of the repatriation files which will tell some of the stories of these families. Stephen Garton looks at the effects of this and other wars and addresses another key issue: ‘Can we find ways to criticise wars, while at the same time hold the valour and sacrifice of the soldiers themselves in high esteem (except when military atrocities have been proven)?’

Clare Wright takes the aftermath issue a step further, exploring what we choose to remember and choose to forget. She quotes Gary Foley’s remark about how ‘the politicisation of historical memory’ has blocked out much of the history of internal violence against the First Australians. ‘Democracy’, Wright concludes, ‘is not what you forget, it’s what you are brave enough to remember’. Working on the implications of how we choose to remember, Peter Stanley finds both that our obsession with Victoria Cross winners is anti-egalitarian and that the award can be an instrument of policy, as during 1918, when a lot of VCs were awarded to Australians pour encourager les autres.

Extremely disabled war veterans association badge, c. 2000 (Australian War Memorial REL38703)

Extremely disabled war veterans association badge, c. 2000 (Australian War Memorial REL38703)

The breadth of contributions in the book illustrates the complexity of war experience. Gerhard Fischer writes about the ill-treatment of German-Australians during World War I, noting how the Hughes government ‘fuelled a jingoistic atmosphere of demarcation and exclusion’, while Joy Damousi addresses the World War II memories of Greek families and how Australian assimilation policy after this conflict ‘failed to take into account the trauma and tragedy of so many of its migrants’. Ross McMullin, Frank Bongiorno and James Brown extend elements of their previous work on ‘Pompey’ Elliott, labour and Anzac, and current attitudes to the military role, respectively. Jeannine Baker explores the stories of female war reporters and Jill Brown looks at what women wore during the Great War. Going back further, Jim Davidson finds distinctive Australian soldiering qualities in the men who went to the Boer War. From Aotearoa New Zealand, Christopher Pugsley shows how his country memorialised its dead at Gallipoli

Turning to more recent wars, Jenny Hocking writes of how Gough Whitlam’s wartime experience as an enthusiastic supporter of the 1944 referendum (to increase federal government powers) influenced his later political life while Tim Rowse explores the stories of Indigenous servicemen in World War II, noting the fears of some White Australians in the North that Indigenous people might side with the Japanese – ‘frontier memories were fresh on both sides’. Paul Ham ventures into the shallow depths of the Australian-American alliance during the Vietnam War and Greg Lockhart sees the minefield as a metaphor for mistaken Australian strategy in that war. Meredith McKinney considers the tension between Japan’s use of nuclear energy and the legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki while Rosetta Allan finds poetry in the stories of Japanese kamikaze pilots. Finally, David McKnight ventures some possibly unfashionable views on action against terrorism.

Among the memoirs, Cory Taylor goes to Cowra for a ceremony at the Japanese war cemetery and finds flag-carrying local war veterans effectively hijacking proceedings, ‘reminding us that on a scale of honourable deaths, those of uniformed Australian servicemen killed in the line of duty are at the very top’. Focusing on Asian deaths also, David Walker makes a case for our taking more notice of the Second Sino-Japanese War 1937-45 (12 million Chinese dead and millions more as refugees) as an integral part of World War II. War in Asia is also the focus for Gerard Windsor, who discusses the ethics of describing Australian soldiers coming apart under fire in Vietnam.

Closer to home, Ben Stubbs writes about Christmas Island during World War II. Intimate histories are the subject for David Carlin (Italian prisoners of war in Western Australia), Tom Bamforth (Great War letters from home front to war front) and Tim Bonyhady (how Kristallnacht affected his family). Barry Hill weaves a meditation from Tagore, Churchill and peace activists trespassing on an SAS base, while John Clarke remembers his friend, Ray Parkin.

Julianne Schultz’s introduction looks a trifle rushed (understandable given the exigencies of herding over thirty contributors) but she makes the telling point that Australians tend to ‘shy away’ from learning lessons from wars. Rather than this essentially intellectual exercise, we prefer ‘celebration, commemoration and consumption’ – the last involving battlefield travel, books, film, TV and memorabilia. Hugh White, Carolyn Holbrook and others have made similar points.

The articles presented show much thought and deserve wide dissemination. Perhaps travel agents specialising in war could offer copies of this book; it will be interesting to see if the Australian War Memorial Shop takes a consignment.

The book is a solid alternative to Anzackery, the overblown and jingoistic – and money-making – celebration of our military exploits. ‘Anniversaries’, says Tim Bonyhady, ‘can be more than occasions for remembrance; they may transform our understanding of what is being commemorated’. Legacies can be invested and produce something rather different from the events that generated them.

David Stephens is secretary and senior website writer of Honest History

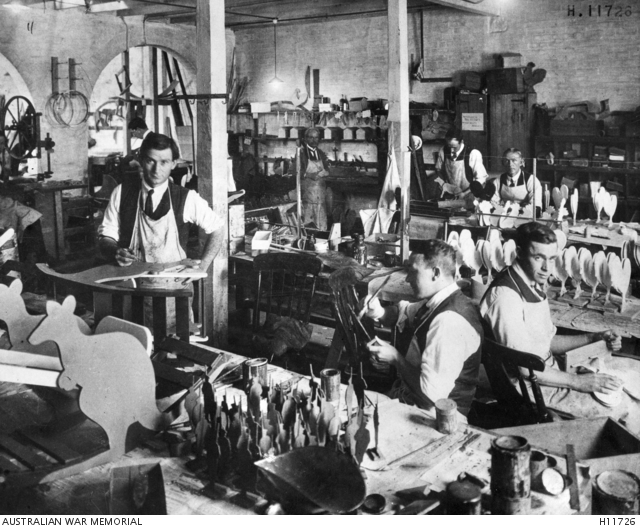

Disabled soldiers making toys in the Red Cross toy industry, Sydney, c. 1918 (Australian War Memorial H11726)

Disabled soldiers making toys in the Red Cross toy industry, Sydney, c. 1918 (Australian War Memorial H11726)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.