Derek Abbott*

‘Worlds behind the legend of Charles Todd, the Overland Telegraph man’ (review of Cryle), Honest History, 19 September 2017

Derek Abbott reviews Denis Cryle’s Behind the Legend: the Many Worlds of Charles Todd

Denis Cryle is to be congratulated for bringing together the vast range of available sources on the life and work of Charles Todd to produce a comprehensive and readable biography. Todd has never disappeared from the historical memory; his name and aspects of his work appear in scholarly histories of exploration and communication and in popular works on the ‘outback’ and pioneers of Australia’s European settlement.

Todd is best remembered for the construction of the Overland Telegraph in the early 1870s. His origins in England and the range of his professional responsibilities in communications, astronomy, meteorology and public administration have been given proper recognition in this biography. Beyond Todd’s public career, his private life provides valuable insights into society and social mobility in both Britain and the Australian colonies.

Todd is best remembered for the construction of the Overland Telegraph in the early 1870s. His origins in England and the range of his professional responsibilities in communications, astronomy, meteorology and public administration have been given proper recognition in this biography. Beyond Todd’s public career, his private life provides valuable insights into society and social mobility in both Britain and the Australian colonies.

Todd was born in 1826 in Greenwich on the Thames into a nonconformist family with aspirations to gentility. He was fortunate to receive a sound basic education. His family was in very straitened circumstances when he went out to work and he learned very early that long hours and strict discipline were to be his lot if he was to contribute to his family’s upkeep and lay the foundations of a career.

Todd exemplified the truth of Mr Micawber’s characterisation of the very fine margin between misery and happiness in Victorian England; as a young man lacking social standing or powerful patrons he had to seize and make the best of every opportunity. This was to be reflected in his own career and also in his domestic life, where the futures of his own extended family were carefully nurtured and promoted. His son-in-law and grandson, WH and WL Bragg, were to win the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1915 – the only father-son winners of the Nobel.

At the age of 15, Todd was employed at the Royal Observatory as a ‘computer’, doing calculations based on the astronomical data collected by the Observatory. The Astronomer Royal, Sir George Airy, worked his staff very hard, demanded a lot from the boys he employed and rewarded those who met his high standards. Todd was one of those and, with Airy’s support, he moved to the Cambridge University Observatory, where he had greater freedom to develop his skills as an astronomer and became involved with the operation of a telegraphic link between the two observatories, a new technology of which he developed a thorough grasp.

It is important to understand that, at this time, the links between accurate time-keeping, astronomy and meteorology were very close, and that the electric telegraph was enabling degrees of accuracy and utility not previously possible. Time-keeping was central to comparing astronomical readings from different sources and to precise calculations of longitude.

Uniform national time systems also underpinned the rapidly expanding railway network. Meteorology was largely the function of astronomical observatories and its practical application in weather forecasting was vital both to maritime trade and to the extension of settlement within the Australian colonies. To be useful, weather forecasting required the ‘real time’ communication that the telegraph provided.

In Cambridge, Todd extended his range of friends and contacts and met his future wife, Alice. As a result of his work with the telegraph he was recalled to Greenwich to resolve problems with that observatory’s link to a coastal station at Deal in Kent. When the Colonial Office approached Airy to recommend a superintendent of telegraphs for the colony of South Australia, Todd was his second choice. Airy didn’t doubt Todd’s technical skill but questioned his ‘boldness’; those doubts were ameliorated by Todd’s successful resolution of the problems with the Deal Telegraph.

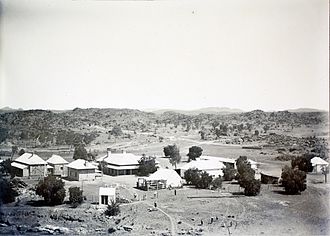

Alice Springs Telegraph Station buildings, 1905 (Wikipedia)

Alice Springs Telegraph Station buildings, 1905 (Wikipedia)

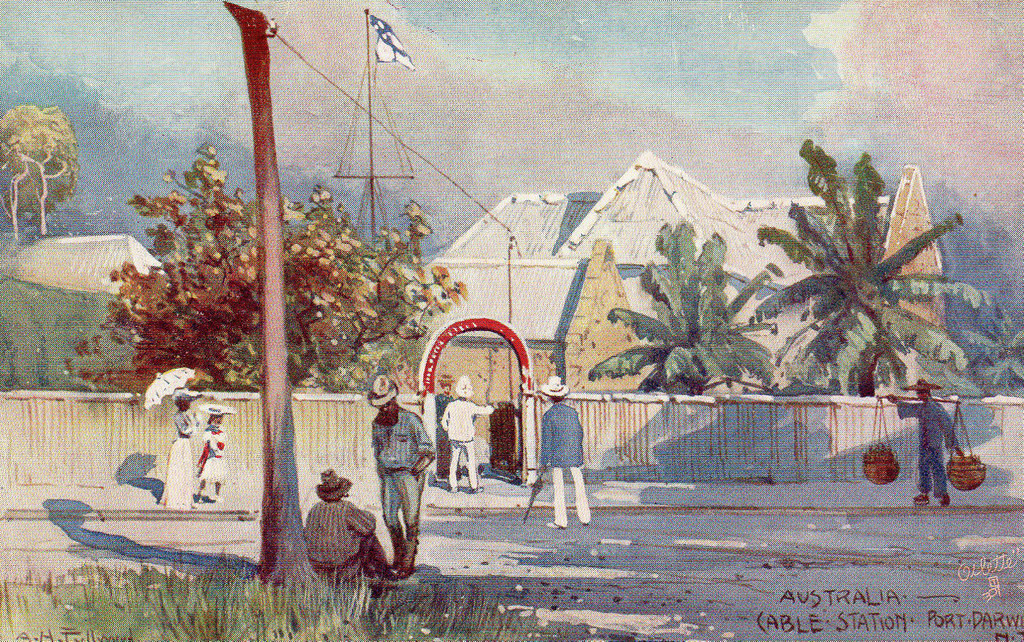

When Todd arrived in South Australia in 1855 the colony was barely 20 years old, the continent had not been crossed north to south and communication depended on sailing ships and on men on horseback. Though Todd had never actually constructed a telegraph line he quickly demonstrated his abilities, completing a line to Port Adelaide and extending the network to settlements beyond Adelaide. The creation of a link to Melbourne – no small undertaking itself – followed.

At this relatively early stage Todd had demonstrated two characteristics that were to be a feature of his career. On the Deal Telegraph and in his dealings with his more experienced Victorian counterpart he showed a willingness to defer to and learn from the greater experience of others – much of his training had been learning by doing – while he also had the ability to retain the good opinion of those with whom he was in competition. For example, a privately run telegraph to the Port already existed and when Todd’s line put it out of business he ‘tactfully’ bought the assets of the business and recruited some of its staff, thus smoothing over any potential hostility from the Adelaide community which could have blighted his prospects in the colony at an early stage.

The Overland Telegraph is the achievement for which Todd is justifiably most famous, combining the drama of a race to meet the very tight contractual deadline (imposed by hubristic politicians) and a pioneering epic of construction. Teams building the 3200 kilometre line carried all their equipment and supplies by camel and horse through harsh, barely mapped country, hot, dry and rocky in the southern and central sections, subject to the monsoonal wet in the north. It had taken John McDouall Stuart six attempts before he succeeded in crossing this country less than a decade earlier. Todd demonstrated his capacity as a planner and organiser of this major project and, having been forced to intervene in the northern section of the project, further showed his ability to lead men and manage the project directly.

The author deals with this part of Todd’s career thoroughly but does not allow it to dominate his narrative. Todd had another 30 years of active public service ahead of him once the telegraph was completed and, while his subsequent career lacked the drama of this period, it was nonetheless significant in the development of South Australia.

Todd sought resources to develop the postal system and the Adelaide Observatory and extend his meteorological observations. His disputes with contemporaries less concerned with what would now be described as evidence-based policy making may be all too familiar to modern readers. His contributions to science and public administration are attested to by his knighthood and, what gave him more pleasure, his Fellowship of the Royal Society.

The man who emerges from this narrative was a self-confessed conservative in the sense that he required evidence that innovations would actually deliver on their promises. Thus, in disputes over weather forecasting, for example, he resisted pressure to compete with contemporaries making heroic predictions or developing theories of cyclical weather patterns on scant evidence.

Todd preferred instead to produce limited but more accurate forecasts, often to the frustration of farmers and ship owners. When faced with the federation of the colonies he accepted the need for a unified posts and telegraph system but favoured building on the strengths of the existing colonial services rather than adopting a centralised system.

This restraint did not blind him to the real potential of innovations; he was an early and enthusiastic promoter of electric lighting, wireless telegraphy and telephony. Nor did this conservatism blind him to the needs of others. He was a progressive employer, particularly where the employment of women was concerned. Todd was to struggle hard in his later years to ensure that his staff were not disadvantaged by the creation of a national post and telegraph system at Federation.

Cable Station, Port Darwin, c. 1900 (Flickr/Aussie Mobs)

Cable Station, Port Darwin, c. 1900 (Flickr/Aussie Mobs)

Todd, like George Goyder the surveyor and McDouall Stuart, was keen to avoid conflict with Indigenous Australians and appreciated that competition for water – and fraternisation, particularly with women – were potential sources of trouble. While his work parties were armed they were under strict instructions to avoid trouble.

The author provides an example of Todd, while he was working on the northern section of the line, declining to take the side of workers who tried to blame the loss of equipment on theft by Aboriginals; he concluded this ploy was a cover for the workers’ own negligence. However, he was a man of his time; violence towards his workers was dealt with harshly.

It requires a considerable effort of the imagination to place oneself into the Australia in which Charles Todd made his name. Today, swishing up the Stuart Highway towards Alice Springs (named for Todd’s wife) a GPS system will tell you where you are within metres; a smart phone with the appropriate apps will give you a weather forecast for anywhere in the world; the same phone pointed at the heavens will name planets, stars and galaxies; and your radio will bring you news from everywhere. Charles Todd would have been fascinated and delighted by it all.

* Derek Abbott is a retired parliamentary officer. He has previously reviewed books for Honest History on Australian home defence in World War II, The Silk Roads, Victor Trumper, sport, Australian foreign policy, World War I at home, Duchene/Hargraves and the discovery of gold, and other subjects.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.