‘Here we go again: complaints about history curricula, this time tertiary’, Honest History, 25 October 2017 updated

There’s been another sprouting of what commentators with a horticultural background once used to call ‘a hardy perennial’ – complaints about how and what history is presented to young people. Two articles in The Conversation link to the most recent evidence of these complaints – growing from a survey by the Institute of Public Affairs of university history courses – and give some reasons why this perennial really doesn’t deserve much watering, except to the extent that continually examining one’s assumptions is a good thing – and that should happen on all ‘sides’ of the debate.

The main findings of The Rise of Identity Politics: An Audit of History Teaching at Australian Universities in 2017 reveals [says the IPA] that history has shifted away from the study of significant historical events and periods to a view of the past seen through the narrow lens of class, gender and race. This major piece of research demonstrates what we have long known; that in general, the substance of Western Civilisation, which is essential to understanding our present and shaping our future is not being taught to Australian undergraduates studying history.

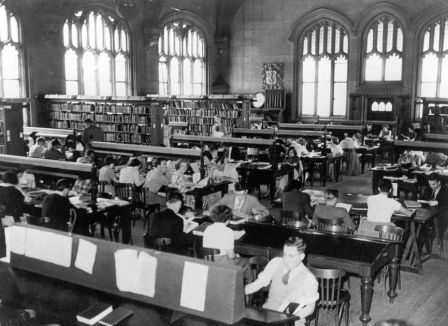

University of Sydney, 1950s (University of Sydney)

University of Sydney, 1950s (University of Sydney)

In the first Conversation piece, Professor Trevor Burnard of the University of Melbourne reminds us that university history departments are driven to a considerable extent by student demands and preferences.

The realities of our parlous funding, however, mean that we have to be responsive to student interest and student demand. The reason British history is less taught now than it once was has little to do with politics, and everything to do with student preferences …

Australians are not as interested in the history of western civilisation as the IPA thinks they are. The practice of history is not, of course, just about giving the public what they want. It is, however, a house of many rooms. The history of western civilisation is just one of those rooms.

The second Conversation piece, by Associate Professor Paul Sendziuk of the University of Adelaide and Associate Professor Martin Crotty of the University of Queensland, denies that identity politics has taken over university history faculties. ‘Counting the number of courses based on “identity politics” is not a realistic way of identifying what most students are studying or how they are being taught about the past’, the authors say. They present, instead, results from a recent study commissioned by the Australian Historical Association:

This shows the most commonly taught and most popular content areas align with the traditional historical “canon”. They consist of broad-scope courses, often centred on the nation state or traditional themes such as “war/conflict”, “the Renaissance”, or the “history of ideas”. Courses that focus primarily on histories of race, imperialism/post-colonialism, sexuality, and popular culture [‘identity politics’ courses, roughly defined] do not make the cut.

There is lots more on the Honest History site about these issues. Try scrolling through the tagged list ‘Using and abusing history‘, looking out particularly for historical novelist Hilary Mantel on history, David Faber on an activist sense of history, Diane Bell’s review of Tom Griffiths’ The Art of Time Travel, Anna Clark on national storytellers, James Loewen on lies my teacher told me, David Rieff on when history does more harm than good, Andrew Kahn and Rebecca Onion on whether history is written by and about men, Matt Houlbrook on not being a one-trick historian, Laura Sangha on what is history for, Michael Conway on the problem with history classes, Eric Foner on knowing and teaching history, and our analysis of the Donnelly-Wiltshire review of the secondary curriculum. (You should be able to track these down also by author name, using our Search engine.)

Then there are some speeches by former prime minister Howard, who has always been interested in history. In 2006, for example, he said:

Too often history has fallen victim in an ever more crowded curriculum to subjects deemed more “relevant” to today. Too often, it is taught without any sense of structured narrative, replaced by a fragmented stew of “themes” and “issues” …

Part of preparing young Australians to be informed and active citizens is to teach them the central currents of our nation’s development. The subject matter should include indigenous history as part of the whole national inheritance. It should also cover the great and enduring heritage of Western civilisation, those nations that became the major tributaries of European settlement and in turn a sense of the original ways in which Australians from diverse backgrounds have created our own distinct history. It is impossible, for example, to understand the history of this country without an understanding of the evolution of parliamentary democracy or the ideas that galvanised the Enlightenment.

Not surprisingly, given his previous remarks, Mr Howard (on 18 October in The Australian but behind a paywall) thought the IPA was on the right track. Janet Albrechtsen weighed in. So did Gideon Rozner in The Spectator.

We’ll keep an eye out for the future work of the Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation (which has former prime ministers Howard and Abbott on board, and whose Facebook page currently has 15 likes). ‘The foundation’, said Paul Kelly in The Australian, ‘will bring a wide perspective to the study of the Western canon in its various dimensions of religion, literature, history and ideas’.

We’ll keep an eye out for the future work of the Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation (which has former prime ministers Howard and Abbott on board, and whose Facebook page currently has 15 likes). ‘The foundation’, said Paul Kelly in The Australian, ‘will bring a wide perspective to the study of the Western canon in its various dimensions of religion, literature, history and ideas’.

On the other hand, we’ll keep in mind the remarks of historians Larissa Behrendt, Peter Cochrane, and the late Inga Clendinnen, which pin down the essential slipperiness – and thus the abiding interest – of the discipline of history.

Clendinnen said [and Alison Broinowski and I quoted her in The Honest History Book] it was the job of historians like her to be “the permanent spoilsports of imaginative games played with the past”; Clendinnen’s fellow historian Peter Cochrane reckoned history is “a cautious, ever-questioning discipline”. “History is not a single story”, Larissa Behrendt writes in her chapter in this book. “It is competing narratives, brought to life by different groups whose experiences are diverse and often challenge the dominant story a country seeks to tell itself. There are no absolute truths in history. It is a process, a conversation, a constantly altering story.”

Those remarks are more compatible with the unruly collection of subject matter available in our tertiary history faculties than with a history course built around ‘Western Civilisation’, or indeed any single big, hairy theme. As Professor Burnard said, ‘Western Civilisation’ claims only one of the many rooms of the history house.

In 2016, Kwame Anthony Appiah talked about Western civilisation in a Reith Lecture. In Australia, the University of Newcastle’s Catharine Coleborne reckoned the concept is outdated as a basis for tertiary courses.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.