John Shield*

‘A Vandemonian war story passionately told’, Honest History, 29 October 2017

John Shield reviews The Vandemonian War by Nick Brodie

If you were slightly unsure about this book and its subject matter before, Nick Brodie does everybody a favour by making his point fairly clear in the first four lines of the preface.

The Vandemonian War was the British Empire’s best-kept secret. Invasion was called settlement. Ethnic cleansing was called conciliation. Genocide was naturalised as extinction. Even Van Diemen’s Land was renamed Tasmania.

So it would appear that there aren’t too many shades of grey in the story Brodie sets out to tell us. Even the cover of his book kind of screams out at you – Governor George Arthur in a frockcoat looking through the letters V and W scratched out of the white cover.

So it would appear that there aren’t too many shades of grey in the story Brodie sets out to tell us. Even the cover of his book kind of screams out at you – Governor George Arthur in a frockcoat looking through the letters V and W scratched out of the white cover.

Brodie starts by describing the startling discovery of a ‘certain manuscript volume’ with the designation CSO1/1/320 (7878). This file comes from the British Colonial Secretary’s Office and, according to Brodie, has rarely been used by historians of the period. Bold statements are made about historians who either neglected or underappreciated the volume. Brodie says quite simply that the file is his key to his ‘discovery of the truth’.

So it is impossible to read Brodie’s book in a vacuum. The book fits within the whole discussion about the black-white conflict post 1788. Captain Cook statues aside, invasion and genocide – let alone the word ‘war’ – are unfortunately imprecise terms. And it is curious how we have got there. In 1966, Alan Moorehead subtitled his book The Fatal Impact, ‘The Invasion of the South Pacific, 1767-1840’. Fifteen years later, Henry Reynolds started talking about ‘the other side of the frontier’. Words matter – and they are the tip of an evidentiary iceberg.

Nick Brodie has put in his two cents’ worth and claims to have uncovered a secret. But the problem is that, as you read the book, it becomes clear that the secret is well hidden. Consider this moment discussing roving parties in 1828-29

Hoping that each mission could improve on the last, Anstey continued to send out roving parties. Other districts most likely followed suit, though no other left such a rich documentary trail. (p. 37)

Like Hansel and Gretel, you’re in trouble if the trail is made of breadcrumbs. And while Brodie tells a fine story it becomes obvious that the evidence is often circumstantial. He is adept, for example, at citing requests for arms and ammunition, and then creating a military strategy from that. Don’t we need more to go on to prove a strategy?

Similarly, the world of 1830s Tasmania is transformed into a battleground, with Western Fronts, Black Operations and Class War. All these terms come with assumptions and, unfortunately, Brodie’s central thesis struggles, because too often he can’t back his statements up. After discussing the use of mercenaries and citing a report from Gilbert Robertson (a District Constable) Brodie writes:

While this reveals some of the ways that traditional animosities continued into the period of active colonisation – and highlights that the Vandemonian War was fought between multiple polities, albeit much of it undocumented – it also illustrates something of Aboriginal desperation and strategy. (p. 61)

Brodie doesn’t leave room for manoeuvre in his statement of intent in the preface. However, we can readily question whether in the confusion, isolation and wilderness there were actually deliberate strategies in place. The interaction between white and black was a complex one, often reactive rather than proactive. There is no doubt that Governor Arthur did oversee a period of increased violence and the forced removal of Aborigines from their traditional lands and settlement. However, to see all this as a deliberate multi-faceted strategy actively orchestrated by the British Government in London, through Arthur, seems to ignore the isolation of, and difficulties of communication with, Tasmania in 1830.

As well as the famous Colonial Office file, Brodie cites the Hobart Courier as an active supporter of Arthur’s strategy. It is perhaps unsurprising that the newspaper actively reported Aboriginal ‘atrocities’ and the retribution visited upon the perpetrators by Arthur’s roving parties. Again, newspaper reports have to be read with an understanding of the environment in which they were produced – and of their audience, who were clearly feeling under siege. And why wouldn’t you feel besieged, living in arguably the most isolated corner of the earth, in a place inhabited by strange people, amid wild landscapes that undermined any certainties you might have brought across the oceans?

So the black wars have now become the Vandemonian War. Name changes seem to be all the rage when discussing Trowunna, the ‘heart-shaped homeland’, which we know as Tasmania. In 1842, the Anglican Church created the Bishopric of Tasmania – acknowledging the gradual replacement of the Van Diemen’s Land moniker which was too often associated with the ‘Vandemonians’, a term linked to the convict past we so casually visit today at Port Arthur. By 1856, the process was complete and Tasmania officially became Tasmania, gazetted and celebrated with a Grand Tasmanian Regatta on the Derwent.

But we still think they in Tasmania are different. Truganini was the story I was taught at school (‘the last of her race’), and that tale, together with the Thylacine, makes Tasmanian history a different thing entirely to those of us from the northern island. Louis Nowra’s The Golden Age and the current wonderful ABC TV series Rosehaven simply continue to confirm our cultural preconceptions about the world across Bass Strait.

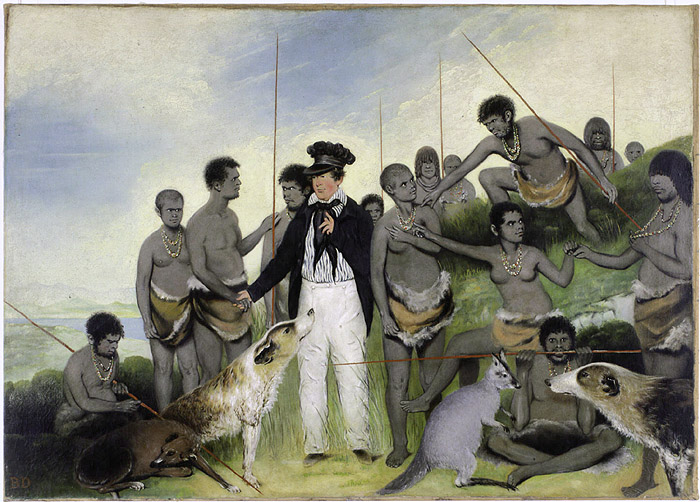

‘The Conciliation’: GA Robinson and Tasmanians by Benjamin Duterrau, 1840 (Documenting a Democracy)

‘The Conciliation’: GA Robinson and Tasmanians by Benjamin Duterrau, 1840 (Documenting a Democracy)

I’m not sure this event or events – the Vandemonian Wars – was the British Empire’s best kept secret. What I am sure about is that to make definitive statements about this most troubling aspect of Australia’s history is probably not helpful, particularly in the absence of mutually reinforcing evidence – and lots of it.

In Western Australia, specifically at Sturt’s Creek, there is an investigation of a massacre alleged to have taken place in 1922. Aboriginal people have been working together with archaeologists and forensic scientists to attempt to uncover the truth of what happened there. The final paragraph of the investigators’ 2016 report indicates both the breadth of the evidence base and the direction of travel:

Based on all of the information presented in the report it was concluded that the forensic soil analysis, pathologist’s report, archaeologists’ reports, the archaeological survey and historical research support the oral history of the Custodians, that is, an unknown number of people were killed at old Denison Downs Station on Sturt Creek, south-east Kimberley Region. In addition, all evidence, or lack of it, in the police report provides compelling evidence of police involvement in both massacres. They were at the right place at the right time and had both the motive and the means to shoot those killed.

I saw a short item about Sturt’s Creek on the ABC News one night when I was in the middle of reading The Vandemonian War. Black armbands, the history wars, invasions and frontiers are all part of Brodie’s story. And he is right in challenging our beliefs about what took place in Trowunna-Van Diemen’s Land-Tasmania. Yet, received views are difficult to topple, particularly when they are comfortable and comforting. Passion, like Nick Brodie’s, helps in this task, but evidence is the clincher. I think I preferred the image of black and white people standing in the remote North Western desert, working together, with that broad spread of evidence, to understand our common history.

*John Shield teaches history at Darwin High School. He has written previously for Honest History: Dylan Voller, Kinchela and the silence about the treatment of children in institutions; how to teach and commemorate Anzac; review of a biography of Chester Wilmot; Top End Anzackery; review of the edited diaries of William Baker Ashton; review of Leigh Straw’s book on the aftermath of the Great War in Western Australia.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.