‘Anzac still a powerful brand after all these years’, Honest History, 6 January 2019 updated

Michael Piggott reviews Consuming Anzac: The History of Australia’s Most Powerful Brand by Jo Hawkins

How doctoral students, still recovering from the physical and emotional effort of producing their 100 000 words, find the strength to face the whole thing again, rewriting it for publication, and often so soon, I do not know. Jo Hawkins earned her qualification at the University of Western Australia in mid 2016 for ‘Anzac for sale: the Gallipoli campaign and Anzac legend in Australian consumer culture 1915-2015’. By the end of 2018, though working full time as a senior project officer, then manager, in UWA’s innovation program, she had produced a major refereed article in Australian Historical Studies, and the title under notice.

War and capitalism: where do you start?  Australia’s experience and prosecution of war, and the interplay of profiteering, industry and commerce, all seem limitless. Then there are the many forms of public and private commemoration, community memory practice and history-making, enabled and exploited by a whole array of interested parties, media companies, merchandisers and sundry rent-seekers, not to mention veterans’ administrators, the RSL, the AFL, and even McDonalds.

Australia’s experience and prosecution of war, and the interplay of profiteering, industry and commerce, all seem limitless. Then there are the many forms of public and private commemoration, community memory practice and history-making, enabled and exploited by a whole array of interested parties, media companies, merchandisers and sundry rent-seekers, not to mention veterans’ administrators, the RSL, the AFL, and even McDonalds.

Many writers have analysed and commented on single aspects of commerce and commemoration within this latter, post-war domain, particularly in relation to Australia and World War I. Here Consuming Anzac stakes its claim. It acknowledges the work of Margaret Anderson, Kylie Andrews, Michelle Arrow, Ruth Balint, and Graeme Davison on the commercial production of history in general, but argues that ‘historians tend to overlook the impact of the marketplace on the collective memory of the Great War’.

So, Hawkins offers ‘a more nuanced understanding of the ways in which various agents have facilitated, sanctioned or contested the production of representations of the Great War in consumer culture since 1915’. She surveys what she calls the ‘correlation between state-sanctioned commemorative events and the private sector production of war memory’, from Gallipoli to planning and funding announcements by Rudd, Gillard and Abbott.

Hawkins’ case study chapters cover the themes of publishing, tourism, advertising and professional sport; doubtless her PhD thesis extended to others. The book chapters are adequate to illustrate the points the author wishes to make. Necessarily, some of these points will depress the reader; Anzac marketing has often had its grubby side.

It is perhaps not obvious from such themes, but the approach is historical. Still, there are echoes of the author’s previous involvement in the advertising and marketing industries, which included work for Sony Music and TBWA Worldwide. For instance, she makes good use of 1920s Attorney-General’s department files to examine the use of the regulation controlling the use of the word ‘Anzac’, and of TNT Magazine, a free London publication with a large antipodean backpacker readership, when she looks at the Gallipoli Dawn Service phenomenon.

The book begins with the almost immediate regulation – in May 1916 – of the term ‘Anzac’, then explains how minimal exceptions regarding it, and about what would be permitted on Anzac Day, were gradually introduced down the decades. It seems anything is allowed, that nothing is ‘sacred’, provided the veterans and their families (aka the RSL and Legacy) get some of the takings. Even the mass production of Anzac biscuits became acceptable, under the 1994 ‘Anzac Biscuit policy’, thanks to lobbying by the RSL’s Victorian President Bruce Ruxton – provided the original recipe was used.

Hawkins also examines the boom in war book publishing and tourist pilgrimages, setting them in the context of the post-1980s war memory boom. Finally, there is Anzac-related advertising, including failures (Woolworths’ 2015 ‘Fresh in Our Memories’, Tiger Airways’ 2009 Anzac Day Sale) and successes (VB’s 2009 ‘Raise a Glass Appeal’, News Corp’s commemorative medallion acknowledging the last surviving Gallipoli campaign Digger, and from 1995 the AFL Anzac Day Clash). (This post refers to a later iteration of ‘Raise a Glass’ but has links to much relevant material. HH)

(ABC)

My only worry about the book was its treatment of its two main underpinning concepts, ‘consumer culture’ and ‘commodification’. They are deployed repeatedly throughout but minimally discussed. The assumption seems to be that we know what they are, particularly commodification – again, most likely extensively covered in the doctoral thesis. We are left to wonder whether the conflation of commemoration and commerce is a worldwide phenomenon, beyond the local peculiarities, including our bizarrely disproportionate Anzac centenary budget and fixation on the Anzac legend, Australia’s most bankable brand.

In fact, there are also a couple of irritations triggered by a glance at the author’s generous acknowledgments. Here she describes Trove as a government-funded resource that provides free access to an extensive archive of digitised Australian newspapers. It is, and it does; but it is also so much more than that, offering ‘books … music, images, maps, archives and more’.

Equally innocent is the author’s casual observation, very widely held and often self-serving, that ‘Humans are hardwired to tell stories’. No, we’re not, but for some reason so many of us so want to believe we are. Read Maria Tumarkin’s ‘This narrated life’ in Griffith Review, or, for a longer rebuttal, Galen Strawson’s book, Things that Bother Me: Death, Freedom, the Self, etc. Tumarkin has this telling conclusion:

“I am just telling a story” – the platitude du jour of our times – is … not a strong enough construction to speak of the essence of what happens, of what gets passed on between humans, in the act of communication. And it is certainly not strong enough, not even close, to fully convey what it is that writers, filmmakers, artists, performers do, that whole doomed Flaubertian enterprise of “longing to move the stars to pity”.

Ultimately, Consuming Anzac leaves us wishing there were more to the book, which is to its credit. Because it (understandably) ends in 2015, as the centenary programs began, a second volume now could easily be sustained. My wish list for such a book would include a chapter on the use of Victoria Cross winners in advertising. (It started in 1917: Hawkins reproduces an advert titled ‘A Gallant Anzac V.C. endorses Rexona’.)

The actual centenary is worth examining, too. We know well over five hundred million dollars was spent, but how much income was generated, who benefitted and how much did they make?

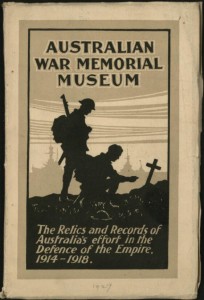

And a chapter, please, on the surprisingly long history of the Australian War Memorial’s own merchandising, which began with the mid-1920s souvenir recycled German helmets and ordnance, and today includes an online shop with its own little version of Bradford Exchange. Scanning the choices available there, one marvels at the subtle insight of Don Watson’s observation made ten years ago that Anzac Day was becoming like a kitsch religion. Hawkins shows us that huckster’s Anzac is, in fact, an old time religion; it was good enough for them in 1916, and it seems we are lumbered with it still.

* Michael Piggott AM is Treasurer of the Honest History association and an archivist with many years’ experience. He has a chapter in The Honest History Book. Michael is currently based at the National Library of Australia as a Senior Research Fellow, Deakin University (ARC Linkage project LP 170100222). He has written book reviews and other pieces for Honest History, most recently on Doug Morrissey on Ned Kelly.

A 1927 booklet, published by the Government Printer (National Library of Australia: NL 355.00740994 A938-2). The full text is here, but see especially pp. 52-54 for the souvenirs, including items made from German helmets. In 1927, the predecessor of the Australian War Memorial was located in Sydney.

A 1927 booklet, published by the Government Printer (National Library of Australia: NL 355.00740994 A938-2). The full text is here, but see especially pp. 52-54 for the souvenirs, including items made from German helmets. In 1927, the predecessor of the Australian War Memorial was located in Sydney.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.