Margaret Pender*

‘Refuting the War Memorial view of Australia’s World War II – or, at least Sydney’s’, Honest History, 5 May 2019

Margaret Pender reviews World War Noir: Sydney’s Unpatriotic War, by Michael Duffy and Nick Hordern

World War Noir: Sydney’s Unpatriotic War, is described by its authors as a prequel to their earlier history of Sydney’s underworld, Sydney Noir: The Golden Years, which covered the 1960s. ‘Between them’, the authors say, ‘the two books form a sort of alternative history of the city, not just the story of the underworld but of its symbiotic relationship with the rest of society’.

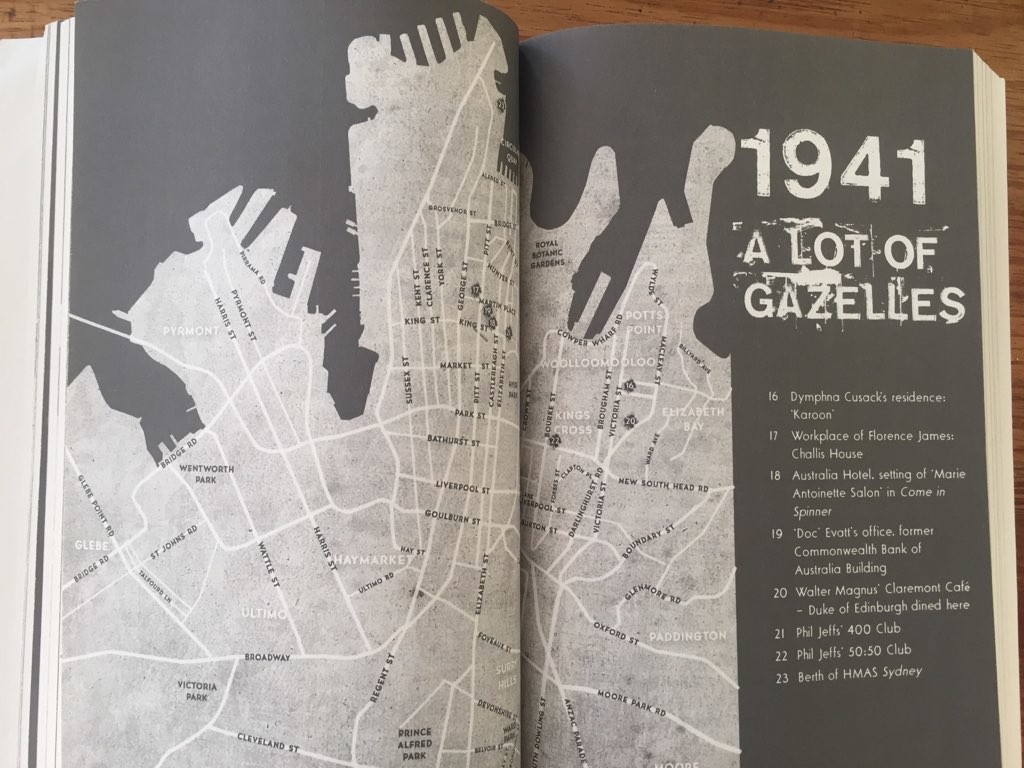

This book’s geographical compass is small, largely confined to Sydney’s inner suburbs – Glebe, Chippendale, Redfern, Surry Hills, Darlinghurst, Wooloomooloo. It’s a poverty- stricken and crime ridden world of its own, where Sydney Noir lived and where it died.

This book’s geographical compass is small, largely confined to Sydney’s inner suburbs – Glebe, Chippendale, Redfern, Surry Hills, Darlinghurst, Wooloomooloo. It’s a poverty- stricken and crime ridden world of its own, where Sydney Noir lived and where it died.

The book is organised along chronological lines, with one chapter for each year of World War II. Each chapter opens with a white on black street map of these inner suburbs, a street directory, in fact, of the main streets of this inner Sydney area, with keys to significant places like the Central Police Courts, Tilly Devine’s brothel and residence. It’s an arresting design feature. (The book’s designer is Josephine Pajor-Markus.)

The book paints a portrait of Sydney in wartime, some 80-odd years ago, and the interaction between police, security authorities, and criminals who flouted the law – and their victims. The authors aver that much crime in Sydney was integral to society and the result of various prohibitions that were a major influence on society, policing and sometimes politics. The demand for prohibited goods and services, principally gambling, in the form of SP or ‘off course’ betting, out-of-hours drinking (pubs closed at 6pm) and prostitution increased significantly with the presence of large numbers of troops on leave in Sydney.

World War II would prove to be Sydney’s closest approach to the actual experience of war. Both the government and the general populace feared invasion by the Japanese. Sydney was the most valuable military target in Australia, its biggest population centre, its region the most important industrial area in Australia, producing the bulk of Australia’s coal supply, its main naval base and dockyards, and one of the chief links in the country’s sea and air communications.

The role of the police was just not to prevent crime and apprehend criminals. Together with the military, the police were responsible for intelligence and security, and protection against threats to infrastructure important to the war effort. The New South Wales Police Commissioner, William John Mackay, an authoritarian Scot (personal telegram address: Nemesis) also became head of the newly formed Commonwealth Security Service (CSS).

Threats to Australia’s wartime security took a number of forms. The fear of a Fifth Column proved baseless; the threat of espionage carried out by foreign agents and Australians under their control proved a concern. Despite anxiety in the CSS, threats of sabotage to industries essential to the war effort did not eventuate. But industrial action by coal miners and on the waterfront was a problem that affected the running of the war and forced the Government to take a hard line against the Waterside Workers Federation and to bring in troops.

The role of the Communist Party of Australia (CPA) in encouraging strike action (at least before Russia joined the Allies in 1941) – and the issue of whether this was treasonable or not – is sidestepped by the authors. They are convinced, however, of the treasonous role played by some CPA members in passing information to the KLOD espionage network and so on to Soviet Russia. Their condemnation seems to extend, beyond the actual CPA members involved, to the wartime Foreign Minister, Dr HV Evatt, whose sympathy towards socialist causes was well known. But equating socialist sympathies with communism seems to me suspect.

The authors claim their book refutes the widely held view that during the war Australians – men and women, military and civilians – put aside self-interest and rallied wholeheartedly to the war effort. They call this view ‘the War Memorial view’ and say it overlooks the diversity of reactions to the war; not everyone believed their highest duty was to the country; some thought their duty was due to their partner or their family or the international working class. Or themselves.

The authors draw on a number of sources for their account of the effect of the war on Australian society. As well as the newspapers of the time – the Sydney Morning Herald, the Daily Telegraph and Ezra Norton’s Truth, they include the works of a number of Australian writers, including novelists Jon Cleary and Eric Lambert, as well as Dymphna Cusack and Florence James, famous for their novel, Come in Spinner, and extracts from the diaries of journalist Gavin Long and artist Donald Friend. Compared with received opinion, these all offer a much more nuanced view of the impact of the war on Australian society.

Overall, this book is a popular history of crime in Sydney during World War II. It’s journalistic in style, with information conveyed in short, one page accounts, without any apparent connection to each other. Accounts of serious criminals and their criminal activity predominate, so much so that at least half the people listed in the book’s dramatis personae, entitled ‘Important People in our Story’ in the front of the book, are convicted criminals. The style of these descriptions is very much of the ‘this happened, then that happened’ without any hints about why it might have happened. Perhaps that’s what the late lamented Pauline Kael described as ‘Kiss Kiss Bang Bang’.

* Margaret Pender is a retired Commonwealth public servant who now does voluntary work at the National Library of Australia. She reviewed Peter Phelps’s The Bulldog Track, Ian Townsend’s Line of Fire and Carol Baxter’s The Fabulous Flying Mrs Miller for Honest History.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.