‘Brooding malevolence in Rabaul 1942’, Honest History, 7 March 2017

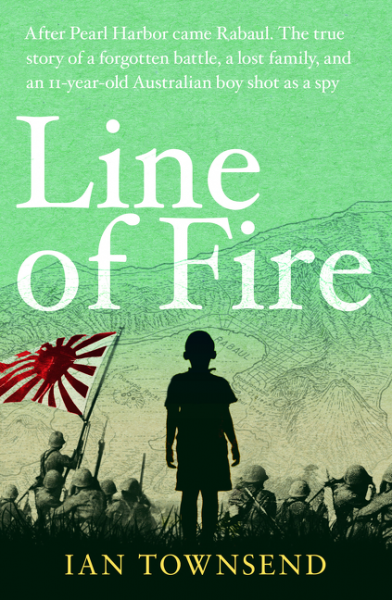

Margaret Pender* reviews Ian Townsend’s book, Line of Fire

This is a book about an atrocity, a war crime that occurred in Rabaul, New Guinea, in the early days of World War II. It’s a detective story, a crime novel, a thriller. It’s also a record of a largely overlooked part of the war in the Pacific, as well as a social history of the period in Australia leading up to that war, with lessons in geology, vulcanology and geopolitics thrown in for good measure.

Like all good detective stories, this one starts with a death – the death of an 11-year-old boy, Richard Manson, his mother Marjorie and her lover, Ted Harvey, plus two other men, one of them Richard’s uncle. The Japanese shot all of them as spies in Rabaul on 28 May 1942. It’s dramatic, it’s cruel and it’s dreadful. It’s meant to shock, and it does. And it is based on fact.

Like all good detective stories, this one starts with a death – the death of an 11-year-old boy, Richard Manson, his mother Marjorie and her lover, Ted Harvey, plus two other men, one of them Richard’s uncle. The Japanese shot all of them as spies in Rabaul on 28 May 1942. It’s dramatic, it’s cruel and it’s dreadful. It’s meant to shock, and it does. And it is based on fact.

Rabaul in 1941 was the capital of New Guinea (excluding Papua), the territory administered by Australia under the Mandate of the League of Nations since 1921. Following Pearl Harbor, the Japanese decided to seize Rabaul: ringed by active volcanoes, it offered a natural harbour for a large fleet and was a strategic point in Japan’s artery of communications extending down to Australia.

Rabaul itself, like Chandler’s mean streets of Chicago, is a character in the story. Its lush beauty and plantation society – likened by Townsend to the musical South Pacific – are, on the surface, idyllic. Its volcanic activity and shifting tectonic plates are a source of riches. Its fertile soil grows coconuts for the copra industry and there is gold and iron beneath the ground. Townsend uses the volcanoes and their constant subterranean activity, the ground heating up beneath the town, as a metaphor for the brewing global war.

Since early 1941 there had been a small Australian garrison at Rabaul, the 2/22nd Battalion (Lark Force) and 24 RAAF Squadron. Both were poorly equipped. After Pearl Harbor, America declared war on Japan on 8 December and four days later the Australian Government ordered the evacuation of all women and children from the territories of Papua and New Guinea. On 20 January, the Japanese bombed Rabaul and they invaded by sea two days later.

Line of Fire is the story of a family caught up in that invasion. The author’s stated aim is to make us more aware of our own history by telling us the story of an ordinary working class family from Adelaide, civilians caught up in a largely forgotten battle in the Pacific. They were among the 1500 soldiers and civilians in Rabaul abandoned by the Australian government as ‘hostages to fortune’.

One of the main feature of stories is that they fuse the ordinary with the extraordinary. The story of Marjorie Manson, a young dressmaker, and her son Dickie is both ordinary and extraordinary. In 1937, they left suburban Adelaide where they lived with her parents and brothers, George, Graham and Jimmy, to follow her husband to Brisbane, where he had found work. Here Marjorie took up with con man and serial bigamist, Ted Harvey, and went to live with him on his plantation, Lassal, on the Bainings coast, west of Rabaul. Two years later, in 1939, Dickie joined her again, along with her brothers Jimmy and George.

Then there is the story of Ted Harvey himself, con man extraordinaire, who volunteered to spy on the Japanese for the Australian government, plus the stories of geologist Norman Fisher and George Manson and their escape from Rabaul to Tol on the Gazelle Pennisula.

The overarching story is Townsend’s account of his quest to find out what really happened. He imagines what it might have been like for the central characters – Marjorie, Dickie, Ted Harvey, her brother Jimmy. He builds on first-hand accounts left by others, like George Manson and Norman Fisher.

Townsend’s research is diligent. The facts accord with those in the official Australian war history, and with regimental records of the time, like those of Lark Force. He has also used a range of witness accounts. Most significantly, he has used the resources of modern genealogical research to search for records of births, deaths, marriages and wills, as well as censuses, electoral rolls and, of course, the National Library’s Trove.

These sources tell us about events that were central to people’s lives but they don’t tell us what these people were like. So Townsend, like many modern writers of non-fiction, has used the techniques of fiction to provide imaginative reconstructions of what happened between people, and what caused them to act in a certain way.

Townsend worked for ABC Radio National, winning four national Eureka Prizes for science and medical journalism. His descriptions of mining towns and conditions during the Great Depression and his explanations of the geology and vulcanology of Rabaul are impressive. But when it comes to fiction – or faction? – he falls down. For me, these imaginative reconstructions of his characters’ lives fail to tell us what first motivated them – what, for example, drove Marjorie Manson to throw in her lot, twice, with unscrupulous men, the man she ultimately married and later Ted Harvey? Surely there must have been more to it than boredom and a desire to escape poverty, which is all that the author seems to suggest.

Townsend’s style is journalistic: short chapters, sometimes with minor cliff hangers, emphasise changes in pace and heighten the sense of danger. There’s a sense of brooding malevolence – the volcanoes again! And reading the book drove me to read the official history and other histories of the time. I want to read more – but not a factional version.

* Margaret Pender is a retired Commonwealth public servant who now does voluntary work at the National Library of Australia.

2/22 Battalion Regimental Band, c. 1941. Only one survived the war, most being killed when the Montevideo Maru, carrying more than 1000 POWs and Rabaul civilians, was torpedoed by the Americans on 1 July 1942 (AWM P04138.002)

2/22 Battalion Regimental Band, c. 1941. Only one survived the war, most being killed when the Montevideo Maru, carrying more than 1000 POWs and Rabaul civilians, was torpedoed by the Americans on 1 July 1942 (AWM P04138.002)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.