John Myrtle*

‘Ambivalent return: how Australia treated former prisoners of war after 1945’, Honest History, 6 March 2018

John Myrtle reviews The Battle Within: POWs in Postwar Australia, by Christina Twomey

Christina Twomey, Professor of History at Monash University, is probably best known for her research on the cultural history of war and with this background has now published a major work, The Battle Within: POWs in Postwar Australia. In the words of the publisher’s blurb, the book ‘follows the stories of 15 000 prisoners of war (POWs) from the moment they were released by the Japanese at the end of the Second World War’.

Christina Twomey, Professor of History at Monash University, is probably best known for her research on the cultural history of war and with this background has now published a major work, The Battle Within: POWs in Postwar Australia. In the words of the publisher’s blurb, the book ‘follows the stories of 15 000 prisoners of war (POWs) from the moment they were released by the Japanese at the end of the Second World War’.

The author’s introduction to the book suggests that a holiday episode from her childhood may well have influenced her subsequent research and writing as an historian. In 1979, her family lived at the Royal Australian Air Force Butterworth base in Malaysia and as an 11-year-old she went on a family holiday excursion to the western province of Kanchanaburi in Thailand.

It was at Kanchanaburi that tourists were introduced to Hellfire Pass, part of the notorious Thai-Burma railway built for the Japanese in deplorable conditions by thousands of allied prisoners and romusha (slave labourers). Kanchanaburi was not then a magnet for tourists and the Australian government was not yet sanctioning official memorial activity in relation to POWs, other than honouring those buried in Commonwealth War Graves cemeteries. The young Christina Twomey visited the JEATH War Museum.[1] ‘Thai monks had established [a] slightly gruesome collection of material in the grounds of a temple. A well-meaning and small-scale affair [on POWs] … The images of beheadings and emaciated men in loin clothes were terrifying to a child …’[2]

In Australia by the 1980s, there was a revival of interest in the POWs, focussing on their stories and the impact of their imprisonment. In Twomey’s words, ‘The 1980s and 1990s were pivotal decades in the rediscovery and discovery of POW history in Australia …’[3] Part of that discovery came through publications such as the acclaimed prison diaries of Edward ‘Weary’ Dunlop[4] and Stan Arneil[5]. This was timely for Christina Twomey, because it was in the 1990s that her career as a cultural historian developed, exploiting a range of archival resources in her research. Her doctoral thesis from the University of Melbourne on the culture of colonial marriages and wife desertion in Victoria used 19th century archives that included the papers of numerous charitable institutions, as well as police records. The thesis was eventually published as Deserted and Destitute: Motherhood, Wife Desertion and Colonial Welfare.

Sister Vivien Bullwinkel and returned POWs, Gunnedah NSW, 1963 (AWM)

Sister Vivien Bullwinkel and returned POWs, Gunnedah NSW, 1963 (AWM)

Twomey then researched a history of Australian civilians who had been interned by the Japanese in World War II, leading to the publication of Australia’s Forgotten Prisoners: Civilians Interned by the Japanese in World War Two. This again had a strong archival background and was based on the papers of the Civilian Internees’ Trust Fund, a fund that provided small cash grants to civilians who had been interned by the Japanese. The archived forms submitted to the Fund by applicants presented testimony of the circumstances of the internees and their post-war struggles.

Twomey became aware that a similar trust fund for former POWs, the Prisoners of War Trust Fund, had been established by the Menzies government. This discretionary fund, initially endowed with a grant of £250 000, was intended to deal with those whose imprisonment might lead to ‘cases of special disability or hardship … not common to other members of the services’.[6]

During the Fund’s operation about one in three former prisoners made applications for assistance, with vigorous vetting, assessing of ongoing disadvantage and hardship, and the application of a means test. Twomey used records of the Prisoners of War Trust Fund that covered 7000 applications for funding over 25 years. In her words, ‘applications to the Fund now provide astonishing insight into the lives, experiences and perceptions of people not usually given to recording or in any event keeping such records of their feelings about the impact of imprisonment’.[7] (A Google search for ‘Prisoners of War Trust Fund’ throws up some examples from the National Archives of applications to the Fund.)

The establishment of the Fund in 1952 had been a grudging government response to campaigns by former prisoners for some form of compensation. A broader revival of interest in Australia’s POWs began in the 1980s but The Battle Within shows that in the early postwar years the POWs were not readily memorialised, feted or praised.

In a revealing case study, the book compares two returned prisoners. ‘Robert’ (pseudonym), an applicant to the Trust Fund, had worked as a bricklayer in the pre-war years and had enlisted as ‘other ranks’. His health had been broken by his imprisonment and he suffered considerable personal and financial problems after the war.

Contrast Robert with Brigadier Arthur Blackburn, a Victoria Cross winner from World War I, who had also been imprisoned in the next war and whose skeleton-like appearance at the time of his return to Australia in 1945 showed his precarious health.[8] Blackburn was a pillar of Adelaide society and served as a conciliation commissioner in the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration from 1947. He was appointed foundation chairman of the Trust Fund and remained in this position until his death in 1960.

Following establishment of the Fund, the trustees told former prisoners that only applications of ‘genuine cases of hardship and distress’ would be considered. Robert had initially received a grant of £100 from the Fund, but a later application in 1958 was rejected. In Blackburn’s words, ‘I don’t think we can get him out of his jam’.[9] The Battle Within highlights the fact that the differences of education, opportunity and wealth that divided former POWs were of longer-term consequence than the experience of captivity that had originally united them, suggesting that, in Twomey’s words, ‘it … allows for consideration of the dynamic of class in the post-war POW community’.[10]

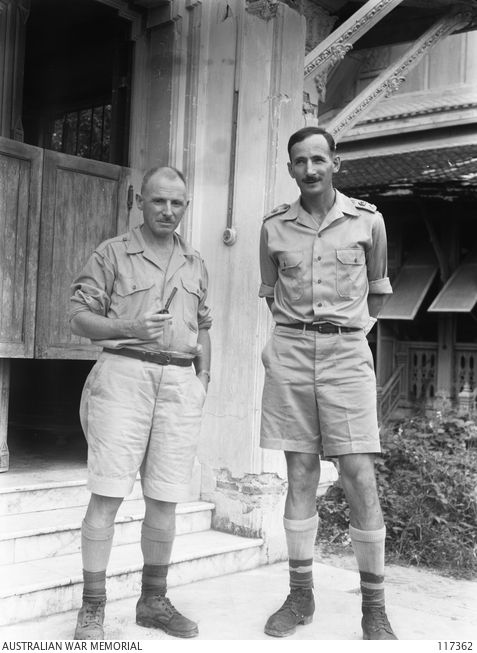

Albert Coates and Ernest ‘Weary’ Dunlop, September 1945 (AWM)

Albert Coates and Ernest ‘Weary’ Dunlop, September 1945 (AWM)

Immediately after the war, the army showed an ambivalent attitude to soldiers who had been taken captive. During the war, there had been a groundswell of support for the POWs. This contrasted, however, with the view of the army chief, General Blamey, who in 1943 had written to his minister that ‘[i]t must be held foremost in mind, that surrender to the enemy on the part of the soldier in preference to death is dishonourable’.[11]

Many former prisoners rejected this attitude and kicked back against the army’s ambivalence. One notable critic of the army was Stan Arneil, who had volunteered as a private in May 1940 and whose diary (first published 1982) had been studied and read throughout Australia. The effect on its readers had been profound.[12] After the war, Arneil worked as an accountant for the ABC and was a pioneer in the establishment of the credit union movement and other co-operative initiatives in Australia. On his return home in 1945, he had been appalled at the army’s maladministration and its indifference to the needs of POWs.

With no support from the army and no clear direction from government, ex-service organisations realised that there was a general lack of understanding of the suffering endured by POWs. Repatriation, the government body responsible for dealing with the welfare and entitlements of veterans, had a view that POWs should not be treated as a ‘race apart’.[13]

By the late 1940s, there was considerable controversy about Repatriation’s response to cases of war-related neurosis, exacerbated by the pressure on repatriation hospitals from cases of psychosis, depression and debilitating anxiety. Prominent medical advisers to Repatriation such as Walter Edward ‘Ted’ Fisher and Albert Ernest Coates, both former POWs, maintained that the psychological impact of captivity had been exaggerated and the incidence of neurosis in returned POWs was no greater than with other returned service personnel. Indeed, Fisher had expressed the view that gastrointestinal infections caused by parasites might account for many of Repatriation’s neurosis cases.

In spite of the indifference of government to the variety of issues affecting POWs, a campaign for a subsistence allowance for POWs began in 1946. The essence of the campaign was that POWs should receive a payment of three shillings for each day of their captivity. The payment would be an allowance in addition to the normal pay accrued during their captivity. The claim was rejected by the Chifley Labor government and, in a bizarre twist, a government minister, probably primed by the army, suggested in parliament that the offering of compensation might provide an incentive for services personnel to surrender to the enemy in future conflicts.[14]

Another issue that annoyed ‘other ranks’ campaigning for compensation was that all officer POWs had received a ‘field allowance’ of three shillings, an extra payment that applied to any officers serving outside Australia during the war, whether or not they were prisoners. The newly elected Menzies government promised to revisit the subsistence allowance issue, this time supported by Ted Fisher and ‘Weary’ Dunlop. The government appointed a committee of three under Mr Justice William Owen to consider the issue, but the committee voted against payment of any subsistence allowance and the government reverted to the more limited option of establishing the Prisoners of War Trust Fund.

The Battle Within covers much more than the campaigns by returned POWs for compensation and for an acknowledgement of their special circumstances. Repatriation entitlements for former POWs improved in the 1970s. In 2001, the Australian Parliament passed the Compensation (Japanese Internment) Act, which granted former POWs of the Japanese a $25 000 one-off payment.[15] By then, of course, the great majority of these POWs were no longer alive and could not benefit from the payments.

Beyond compensation, the book also deals with the personal issues of POWs as they struggled to cope in postwar Australia; for many, this meant rebuilding their marriages and coping with fragile family relationships. Also the postwar period was an era in which POWs – indeed, all former service personnel – needed to come to terms with a change in Australia’s regional alignments and a government seeking to establish closer relations with Asian countries and achieve reconciliation with Japan as a former enemy.

The book is the product of an extended period of research and writing and we are richly rewarded by the final publication which includes detailed, accessible endnotes and a valuable bibliography. Professor Joan Beaumont, a friend and former colleague of Christina Twomey, has described The Battle Within as ‘a compelling and important book’.[16] I certainly agree with this assessment.

* John Myrtle was principal librarian at the Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra. He produces Online Gems for Honest History, drawing upon his extensive database of references, and has written a number of book reviews for us (see our Search engine). He has also explored the history of the Arthur Norman Smith lectures in journalism.

Notes

[1] JEATH: Japan, England, Australia, Thailand, Holland; a reference to the nationality of those who worked on Thai-Burma railway.

[2] Twomey, The Battle Within, p. xii.

[3] Twomey, p. xiv.

[4] EE Dunlop, The War Diaries of Weary Dunlop: Java and the Burma-Thailand Railway 1942-1945, Penguin, Ringwood, Vic., 1990.

[5] S. Arneil, One Man’s War, Sun, South Melbourne, 1982

[6] Twomey, p. 76.

[7] Twomey, p. xvi.

[8] Twomey, pp. 6-10.

[9] Twomey, p. 10.

[10] Twomey, p. 11

[11] Minute to the Minister for the Army, Frank Forde (cited Twomey, p. 16).

[12] Clare Pettigrew, ‘The spirituality of Stan Arneil’, Australasian Catholic Record, vol.78, no.1, Jan. 2001, p. 88 (an article by Arneil’s daughter with useful biographical details).

[13] See Twomey, p. 253, footnote 4, for a description of Repatriation’s administrative arrangements; originally established in 1920 as the Department of Repatriation, thence the Repatriation Commission, and now the Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

[14] Twomey, pp. 60-61.

[15] Twomey, p. 238.

[16] Front cover of The Battle Within.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.