‘Monash interpretive centre (Immersion II of II): Public Works Committee dips toe in water’, Honest History, 4 August 2015 updated

We find it difficult to treat this project as anything other than a massively self-indulgent and boastful boondoggle*, replete with meaningless puffery and rash assumptions. The Public Works Committee (PWC) did its best, given its very limited writ, to examine the project, while recognising the die was well and truly cast by government decision, drawing its inspiration from a bright idea three administrations back. But the PWC couldn’t ask the key questions.

Architects’ drawing of Monash centre showing immersive experiences (ArchitectureAu)

Architects’ drawing of Monash centre showing immersive experiences (ArchitectureAu)

In our previous article, we analysed the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) submission to the PWC inquiry into the project. Since then, we have attended the PWC’s public hearing on 26 June and seen the proof Hansard (from which most of the quotes below are taken). (Final Hansard with page numbers as in proof.) Update 19 August: article on PWC’s report on the project.)

The PWC heard from DVA officials and consultants involved with the project. DVA’s senior official present, MAJ GEN Dave Chalmers, opened proceedings thus:

Between 1916 and 1918, 290,000 Australians served on the Western Front. Forty seven thousand of them died and another 130,000 were wounded. Despite the special place that Gallipoli holds in our nation’s story, Australia’s greatest achievements and greatest losses of the First World War were on the Western Front in France and Belgium. It is the Australian government’s view that these remarkable and little-known achievements deserve to be better known and recognised both in Australia and internationally. (p. 1)

Parsing the DVA submission last time, we noted that it included five polysyllabic adjectives in a short sentence describing the proposed centre. (One of those adjectives, ‘immersive’, appeared 14 times in the submission of 20 or so pages.) General Chalmers easily broke the record with this opening salvo at the PWC:

The design of the centre presented in this submission envisages an international-standard interpretive centre, with a leading-edge integrated multimedia experience that will provide an evocative, emotional, informative and educational experience for visitors. The centre’s design will, through the use of a range of interpretive multimedia technology, provide a compelling story of Australia’s service and sacrifice on the Western Front. (p. 1)

We’ll call that nine adjectives. ‘State-of-the-art’ pops up later in the hearing as a tenth adjective.

For the most part, the PWC did not poke further into this verbal flummery to try to find meaning. (There was a brief discussion of how the ‘leading-edge’ multimedia features would work.) Instead, the Committee dealt mostly with issues like car parking, disabled access, visitor figures, tourism impacts in the local area, management of technology, the tendering process, heritage listing technicalities, and whether half-burying the centre (to avoid detracting from sight-lines to the existing memorial) added significantly to costs.

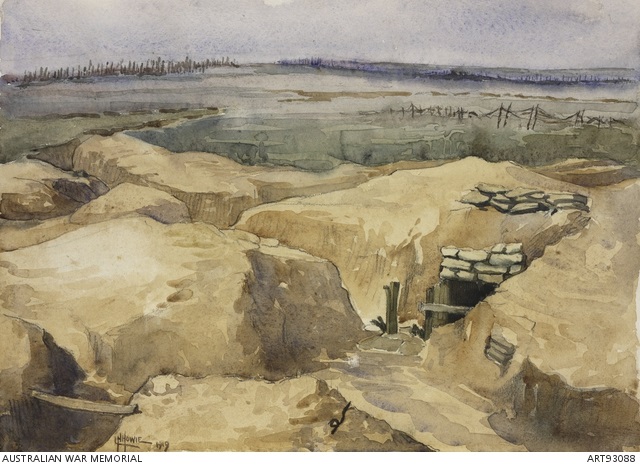

Valley regimental aid post, Villers-Bretonneux, Laurence Howie (Australian War Memorial ART 93088)

Valley regimental aid post, Villers-Bretonneux, Laurence Howie (Australian War Memorial ART 93088)

The answer to this last question was essentially that, while digging the centre into the ground made the project a bit more expensive, a more important driver was the desire to build a high-quality (insert one or all of ten adjectives listed above) centre and one that would attract visitors. As General Chalmers said at one point, in response to questions which noted that other countries’ commemorative projects on the Western Front had been cheaper, ‘you get what you pay for’.

This exchange took place:

Mr Appleton [DVA]: In the functional design brief which the Commonwealth devised, we spelt out that this building and its contents needed to be sufficiently compelling in character that they would change patterns of visitation to the battlefield, and there is a cost premium in that. The concept for interpretation you have heard outlined is without peer. That also comes at a significant cost but it is our belief that that very significant point of distinction is going to draw a new audience to this very important site.

Ms [Sharon] CLAYDON [ALP Member for Newcastle]: Thank you. My understanding, to wrap that, is that because this particular site has been chosen there are some significant costs in having to do a cut-in in order to comply with the French and trust requirements and there are additional significant costs because you do not currently at that site have the visitation rates that you would be wanting and in order to compete with other sites along the trail and other parts you need a monumental building of great significance. Is that a fair summary?

Mr Appleton: I would not say this is a monumental building.

Ms CLAYDON: I would.

Mr Appleton: We specifically did not seek a monumental building.

Ms CLAYDON: I do not mean that in a derogatory way. I think it is terribly monumental. It is very “Canberra-esque” actually.

Major Gen. Chalmers: The two points you made in summary there are correct but to me they are not really the most compelling reasons for developing a building and an interpretive fit-out which is at world standard and at least as good as, if not better than, any other on the Western Front because the Australian story of service and sacrifice on the Western Front deserves to be told and to be told in a way that reflects the story. (p. 9)

In summary, if you want to attract the modern tourist you need a ‘whizzo’ (20th century adjective), ‘OMG’ (21st century adjective) experience to do it. And the service and sacrifice of Australians a century ago merits such an experience.

The PWC’s ability to probe such arguments is, of course, formally limited by its terms of reference. The Committee’s role is set out in its legislation. Briefly, the Committee looks at the purpose of the work, its fitness for purpose, the need for it (‘the necessity for, or the advisability of, carrying out the work’), cost-effectiveness, revenue expected (if applicable) and the value of the work. As we noted in our previous article, the PWC’s consideration of ‘need’ is usually perfunctory. Effectively, the need question has been answered by the government decision to commit to the work – and that decision has been taken and announced before the PWC gets involved. (If the PWC receives submissions critical of a project then resolution of the need issue becomes a little more complex.)

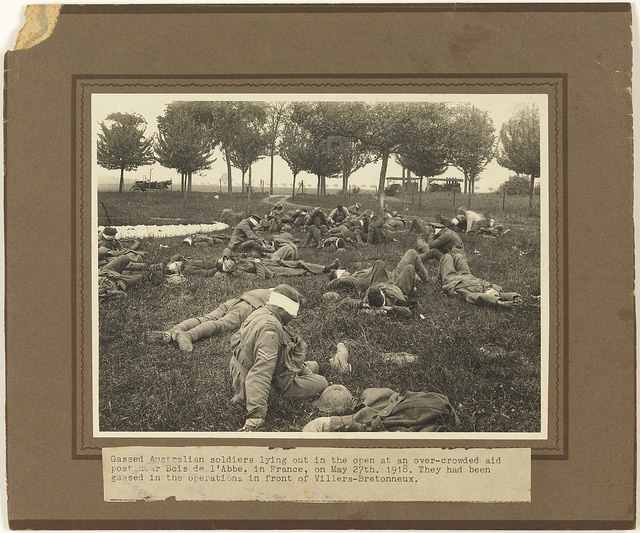

Gassed Australian soldiers near Villers-Bretonneux, 1918 (Flickr Commons/Tasmanian Archives and Heritage Office)

Gassed Australian soldiers near Villers-Bretonneux, 1918 (Flickr Commons/Tasmanian Archives and Heritage Office)

The capital cost of the Monash centre ($93 million) is coming from the Defence budget, rather than the Veterans’ Affairs budget. (DVA is covering operational costs.) The money, said General Chalmers, ‘is offset by the Department of Defence so it is not coming out of Veterans’ Affairs. It has no impact at all on Veterans’ Affairs programs or on veterans.’ (p. 4)

So, the capital cost impact is on Defence. Has the sensitivity of the Veterans’ Affairs portfolio about commemorative expenditure encouraged it to organise a deal with Defence? The Appendix to this article shows where the expenditure is found in the 2015 Budget papers. Meanwhile, Honest History is still counting the Monash centre as commemorative expenditure, regardless of which portfolio label it carries.

Honest History has tried to find precedents for such a large expenditure on a commemoration project coming from the Defence budget. We have been unsuccessful. We asked DVA, ‘are there any precedents for Defence money being used for commemorative works such as the Monash centre?’ The department’s response referred to the construction of ‘the Hellfire Pass Memorial Museum in Thailand and the Sandakan Memorial Park in Sabah. All costs [of these projects] were borne by the Commonwealth‘ (emphasis added). Yet both of these projects were relatively small by comparison with the Monash centre – the Hellfire Pass Museum cost $1.6 million in the 1990s – and they are hardly other than formal precedents. It is the amount of spending that is important here and one gets the impression that $93 million, pointed in the right direction, could buy quite a lot of defence.

We do not know officially why the PWC did not pursue the Defence budget question. We put these questions to the Chair, Senator Dean Smith:

(1) Are there any precedents for commemorative works of the Monash centre’s value ($93 million capital cost) being funded from the Defence budget?

(2) Why did the Committee not probe the issue of why the Monash centre is being funded from the Defence budget?

The Senator’s office advised that they were unable to provide any advice additional to that provided by the PWC secretariat. The secretariat did not know of precedents (citing limited corporate knowledge and limited time to research) and could not discuss the second issue because it was beyond the PWC’s role to ask which portfolio’s bucket of money was being used.

Meanwhile, there are a couple of hints in the PWC hearing transcript that some informal constraints that were evident in the earlier Senate Estimates inquiry still apply. (See our article ‘Commemoration wedging?‘ which looked at Minister Ronaldson’s claims that Labor did not support the project.) Labor Senator Alex Gallacher, who had tangled with the Minister in Senate Estimates, began his PWC questions thus: ‘No amount of money or commemorative works can equal the sacrifice that was made. There is no suggestion in any of my questions that this is not a good proposal.’ The Senator then went on to ask some cautious questions about costs.

The project which will doubtless sail through the PWC has a long history, as the DVA submission noted. There was a feasibility study underway as early as 2005 but the project slipped from sight during the Rudd-Gillard era, despite the interest of those governments in ensuring that the Anzac centenary was appropriately marked.

The current prime minister fervently believes the Australian role on the Western Front needs a higher profile, both generally and compared with the Gallipoli defeat. (Whether DVA officials believe this is beside the point; they are public servants.) The prime minister spelled out his approach most clearly in his speech at Villers-Bretonneux in April this year, when he spoke about the Monash centre. But one wonders whether an earlier prime minister, John Howard, whose father and grandfather were both in battalions that fought at Villers-Bretonneux in 1918 (as he records in chapter 1 of Lazarus Rising), might be the national leader most pleased by the impending Monash project. We asked Mr Howard for a comment but nothing had been received by deadline.

The Monash centre will not be all bells and whistles and tributes to giants of the past, however. An admirable feature of the proposed centre is its planned use of primary sources generated by ordinary folk.

One of the key focuses of the centre and one of the unique approaches we are taking here [according to project consultant, Russell Magee] is that we are not … having text written by historians; all of the text will be first person sourced. They are the people who experienced it and they are the people who can best explain the impact of that terrible event to us. (p. 5)

Sir John Monash on the Australian hundred dollar note. It will take a million of these to build the Monash centre.

Sir John Monash on the Australian hundred dollar note. It will take a million of these to build the Monash centre.

There will still be historians involved in the project – we are told there will be a team of them – and they will doubtless do their professional best to make the centre’s content robust and soundly-based in evidence. They must, however, have in the back of their minds that their work will be subordinated to glittering technology laid on to attract the burghers and teenagers of Northern Europe, who will make up most of the interpretive centre’s clientele (see our previous article). Whether these clients will complete their brief visits with a better idea of the Australian contribution on the Western Front is a moot point. They may wonder, instead, why a sunburnt country on the other side of the world is still trying to come to terms with battles fought a century ago in the mud of France.

It is good also that the centre will not be simply a shrine to the eponymous Monash. DVA’s Chris Appleton told the PWC:

General Monash will stand out in here, but I would like to make it clear for the record that, while this is the story of Monash, Monash was one of more than 290,000 Australians. He was a great Australian; but, as I spelt out earlier, in the great Australian tradition the central character of the Australian story of war is the ordinary man and woman who we throw into extraordinary circumstances. You spoke about what might live forever or live still in 100 years time: their words will live forever. (p. 11)

The plain words of men and women of the time will be a pointed contrast to the hyped-up Anzackery that characterises much of the current centenary commemoration. It is a pity that plain words are not more evident in the justification for this project. Who, for example, made the judgement that $93 million of Defence money spent on commemorating dead soldiers was better value than $93 million spent on live members of today’s Australian Defence Force or on their equipment or their accommodation or their families? What was the reasoning? Where is the evidence that Australia’s ‘remarkable contribution’ on the Western Front is not well enough known? How will we measure when we have made it well enough known? Will we just keep building whizzo/OMG interpretive centres until the visitors begin to flow – or, rather, until ‘visitation’** figures reach a satisfactory level?

Are projects like this too easily characterised as arising from an Australian desire to memorialise every place where an Australian took a piss during the Great War? (These are the words of an un-named British historian reported, with relish, in New Zealand.) Put more politely, in the terms that historian Graeme Davison used in his Menzies Lecture in 2009, is this project yet another example of our yearning to see ourselves writ large in the eyes of others?

General Chalmers told the PWC that the centre ‘provides a once-in-a-generation opportunity to recognise Australia’s remarkable contribution on the Western Front’. All the adjectives being tumbled out to justify this project may be indicative of something deeper than a need to impress the PWC. Is this project just another massive Aussie skite*** to First World countries? ‘The Little Boy from Manly‘ has become the Boxing Kangaroo, Rule Britannia has translated into ‘Aussie, Aussie, Aussie, Oi, Oi, Oi!’, but still the cry from Terra Australis is ‘Look at me! Look at me!’

* A boondoggle, according to Wikipedia, is ‘a project that is considered a useless waste of both time and money, yet is often continued due to extraneous policy or political motivations’. Wikipedia says its article needs improvement but that definition seems spot on to us. A classic boondoggle, according to the Washington Post, is the F-35 joint strike fighter to which Australia has signed up at a cost of $12.4 billion.

** Promoters of the project use the word ‘visitation’ rather than ‘visits’ or ‘visitors’. DVA’s Chris Appleton, for example, talks about changing ‘patterns of visitation’. While some dictionaries give ‘visitation’ as a synonym for ‘visit’ the longer word is more commonly applied to forms of official visits, as by a bishop to his diocese. Using the word for battlefield tourism could be seen as adding a layer of solemnity.

*** Skite (verb) meaning to big-note, brag, boast.

Appendix: Sir John Monash returns to the Defence portfolio

This appendix shows where the Monash Centre features in the Budget papers 2015-16. At page 18 of the Defence Portfolio Budget Statements 2015-16 ‘Sir John Monash Centre – Villers-Bretonneux, France’ appears as a ‘Budget Measure’. The Monash Centre entry at page 18 carries this footnote: ‘The cost of this measure will be met from within existing resourcing of the Department of Defence’. In the consolidated Budget Measures paper (Budget Paper No. 2), however, the Monash Centre appears not under the Department of Defence but under the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, although the note there (page 184) says:

The capital cost of this measure will be met from within the existing resources of the Department of Defence. The operational costs of this measure will be met by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs. Funding for this measure has already been provided for by the Government.

(It is not clear when this provision was made, of which more below.) The project also features in the DVA budget glossy brochure, which notes that capital funding is from Defence and operational funding from DVA.

Program (or Programme) budgeting requires that projects achieve outcomes, aim at objectives and deliver deliverables. Progress is measured against key performance indicators. The Defence budget information shows the Monash Centre under ‘Programme 1.9 Chief Operating Officer – Defence Support and Reform’. The Objective, Deliverables and Key Performance Indicators for that Programme (pp. 59-60) are given below. The statements rendered in bold are Honest History’s guesses as to those which are relevant to the Monash Centre.

Outcome 1

The protection and advancement of Australia’s national interests through the provision of military capabilities and the promotion of security and stability.

Programme 1.9 Objective

This programme contributes to the achievement of outcome through:

- developing and delivering a strategically aligned, affordable, safe and sustainable estate that enables Defence capability and operations.

- efficient and responsive delivery of an agreed range of services that enable the Australian Defence Organisation, and are fundamental to generating Defence capability and preparedness.

- developing and delivering corporate services that best support Defence’s ability to effect necessary reforms.

Programme 1.9 Deliverables

- Manage and sustain the Defence estate to meet Government and Defence requirements by developing and delivering major infrastructure, property, base security improvement, and environment programmes. The approved 2015-16 Major Capital Facilities Programme is outlined at Appendix C.

- Maintain single service, joint, combined and coalition capability by providing training area and range management, estate development services, and coordinating support to major domestic operations and exercises.

- Deliver agreed base support services and other services to Defence.

- Provide accurate, timely, high quality advice and support to the Defence Ministers, CDF, Secretary and the Government to enable effective decision making and policy engagement.

- Increase public awareness of Defence activities and achievements and strengthen Defence capabilities in media-related activities to promote Defence’s reputation.

Programme 1.9 Key Performance Indicators

- The Defence estate is managed and maintained to meet current and future Defence capability and Government priorities.

- Approved Major Capital Facilities Projects are delivered within budget and schedule, compliant with legislative and other statutory requirements, standards and policies.

- Agreed base support and other corporate services are prioritised and delivered to enable Defence capability requirements.

- Timeliness and quality of advice, including Cabinet documentation, provided by the Department meets requirements.

It will be seen that only one statement above has been bolded and the relevance of that one to the Monash Centre is marginal, given that Defence today can only take limited credit for the achievements of Australians a century ago.

Although work on the Monash Centre is expected to commence early in 2016, Appendix C referred to above does not include the Centre in the Approved Major Capital Facilities Programme 2015-16. The second KPI above is thus not relevant. In any case, it is difficult to see the Monash Centre as part of the ‘Defence estate‘, to which Appendix C relates. (Why, for example, would DVA be administering the construction of an addition to the Defence estate?) The list at Appendix C does include works like barracks, hangars, training facilities, communications networks, site security systems and various big sheds – but not the Monash Centre.

The mention of sheds reminds us that we noted above that it was not clear at what date the funding provision for the Centre was made. Was $93 million sloshed into the Programme 1.9 bucket some time during the Centre’s long gestation, on the understanding that it would be spent on the Centre? Or will Defence be pouring out of the bucket $93 million that was originally intended for something quite different, perhaps a barrack or a very big shed for housing amounts of bulky kit? If the latter is the case, then the ‘immersive’ Centre is (appropriately) being paid for out of a slush fund.

By contrast with the Defence budget papers, with their lack of relevant information, we have the Veterans’ Affairs budget papers, which seem very accommodating to the Monash Centre project. Indeed, this is where the operational spending on the project is found, under Programme 3.1 War Graves and Commemorations. Prima facie, the capital spending might have found a home there also. The hierarchy reads thus (at pp. 66-69 of the above-linked document):

Outcome 3

Acknowledgement and commemoration of those who served Australia and its allies in wars, conflicts and peace operations through promoting recognition of service and sacrifice, preservation of Australia’s wartime heritage, and official commemorations.

Programme 3.1 Objective

Acknowledge and commemorate the service and sacrifice of the men and women who served Australia and its allies in wars, conflicts and peace operations.

Programme 3.1 Deliverable

Provide new Post War Commemorations.

Programme 3.1 Key Performance Indicator

Commemorations are provided within published timeframes to meet Australian standards of production/construction.

The problem seems to be that DVA, unlike Defence, has no program for building big things; it has nothing like Defence’s ‘Approved Major Capital Facilities Programme’. So someone else had to do it.

Bottom line: someone conjured up a lazy $93 million in this Defence ‘shed-building and other big things’ bucket to fund a fancy museum on the other side of the world. Like spending on many boondoggles the spending on the Monash Centre was ‘snuck in’ under a heading where it does not fit.

If our analysis is wrong, our website is always open to correction. As usual, we will reprint responses unedited. Or readers can simply use the comments function.

I think that you are victims of your own lofty self importance and victims of ‘long distance isolation’ over this and are looking at this project from too far away. Whilst I am not sure about the price ticket I am sure about the purity of purpose of this project.

Many thousands of Australians visit the WW1 battlefield of France and Belgium ever year, in rapidly and ever increasing numbers. Their first and ‘holiest’ port of call is Villers-Bretonneux. VB is to Australians as the magnificent Vimy memorial is to Canadians. As it should be. We do not have anything near to Vimy and we should/must have. Abbot is correct. The Western Front has suffered for far too long as the second cousin to Gallipoli. We also know what we are talking about as a leading n Australian Battlefield Tour company based in the UK. An interesting article on this was published back in 2012: https://tinyurl.com/nu3pfrm

“However, our existing Western Front memorials, despite their impact, are obsolete. What is required on the Western Front is the idea of a living and permanent Australian presence.

“A model exists for this: it is what the Canadians have achieved at their magnificent national memorial at Vimy Ridge, just 15 minutes’ drive from the French provincial city of Arras.”

“Any Australian who visits the Western Front should include Vimy Ridge in their itinerary to grasp how superior, sophisticated and sensitive is Canada’s model and how inferior is the Australian counterpart.”

Sincerly

Graeme Archer

Director

Spirit of Remembrance

http://www.Battlefield-Tours.com.au