Gareth Knapman*

‘The Batman Treaty’s feudal obligation to the Kulin and the unpaid debt of $68 million a year’, Honest History, 10 February 2022

[Dr Knapman is writing a book which addresses the question, how did British colonial figures understand sovereignty, possession and Indigenous ownership in Asia and Australia? In this article, Dr Knapman argues that, while previous authors have acknowledged that the Batman ‘treaty’ was a feudal document, they have not sufficiently examined the implications of this fact. HH]

The Batman Treaty began the colonisation of Victoria, but the treaty was not a land sale agreement. It was instead a feudal relationship bonding John Batman to the Kulin, the traditional owners of the Port Phillip region. The agreement stipulated up to $A68 million a year (in today’s money) in tribute to Kulin Elders.

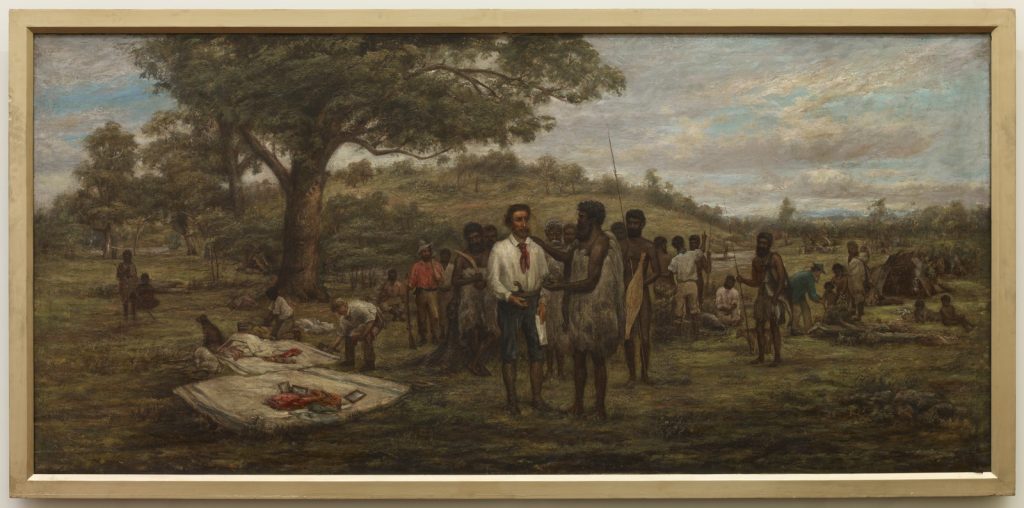

‘Batman’s treaty with the aborigines at Merri Creek, 6th June 1835’, John Wesley Burtt, c. 1888/State Library of Victoria

‘Batman’s treaty with the aborigines at Merri Creek, 6th June 1835’, John Wesley Burtt, c. 1888/State Library of Victoria

In Victoria today, there appears to be real commitment and progress to developing a modern treaty relationship between First Nations and the State government. The government is considering a permanent Indigenous voice in the state’s political and legislative framework. The Age reported this, in language redolent of the 1830s, as a ‘black parliament’.[1] In real terms, that voice may involve a separate body or new seats in the existing State parliament. Melbourne City Council is proposing a First Nations precinct, which could house the new parliament, as well as becoming a keeping place for repatriated artefacts and First Nations remains that cannot be returned to Country.

These important steps are at once practical and symbols of reconciliation, but it is well worth considering the original Batman Treaty that was rejected by the governments of both Britain and New South Wales in 1835. Batman was an opportunist bushman who had murdered Palawa Tasmanians during the Black War. His unsavoury past has led historians to interpret the Batman Treaty as a ‘land grab’. The idea that the land was ‘sold’ has been the basis of criticism from 1835 onwards.

Modern historians argue that the Kulin Elders would never have agreed to the ‘sale’ if the matter had been explained to them correctly.[2] Yet, while observing that the Batman Treaty was about the sale of land, modern writers have merely repeated the contents of newspaper reports of the time, which refer to ‘sale’ and ‘purchase’ and not the wording of the actual document.[3]

Despite the frequent focus on sale of land, the words ‘sold’, ‘bought’, ‘purchased’ or even ‘own’ – words that would normally be used for a transfer of ownership of land – are not found in the Batman Treaty. Instead, the Kulin Elders were described as ‘possessed of the tract of Land’ and it was stated that a ‘tribute’ was to be ‘deliver[ed]’. The delivery of the tribute would enable Batman to ‘occupy and possess the said tract of Land and place thereon Sheep and Cattle Yielding and delivering to us and our heirs or successors the yearly Rent or Tribute’. [4]

The idea that the land was ‘sold’ reflects modern commercial interpretations of the words ‘occupy and possess’. The actual wording of the document suggests it refers, however, to a land use agreement with a yearly tribute assigned to it. Despite what was reported in the newspapers at the time and in subsequent interpretations, the ‘Deed’ says nothing about purchasing land.

The Batman Treaty was, instead, a ‘feoffment’, which was a feudal agreement of service in exchange for land use at the exclusion of other settlers. The treaty was not a modern land sale agreement. Yet, beyond acknowledging the feoffment as an idiosyncratic fact, and questioning if Batman fulfilled all aspects of the feoffment ritual, historians have not placed any meaningful importance on the feudal nature of the agreement.[5]

As a feoffment, however, the Batman Treaty was not primarily a deal about land but, like all feudal agreements, it was a pledge to a relationship. The key phrase in the document is that the ‘Tribe Do for ourselves our Heirs and Successors Give Grant Enfeoff and confirm unto the said John Batman his heirs and assigns’ (my emphasis).[6] ‘Grant Enfeoff’ meant that Batman (and his successors) were required to provide feudal services to the Elders and Tribe. Their access to the land was conditional on their maintaining a relationship of obligation to the Kulin.

The Batman Treaty (first page of two), State Library of Victoria MS 13484

The Batman Treaty has often been mocked for its payment of handkerchiefs, blankets, knives, tomahawks, suits of clothing, looking glasses, scissors, and flour. However, trade goods were not cheap in the 19th century. Adam Smith opened his The Wealth of Nations by examining how specialisation could reduce the cost of pin manufacture. Although pins are trifling objects nowadays, they were extremely expensive in the late 18th century and appeared as valuable items in wills and dowries. Similarly, providing handkerchiefs, tomahawks, blankets, and looking glasses to the Elders annually entailed considerable expense for Batman and the Port Phillip Association.

When Batman returned from Port Phillip to Van Diemen’s Land, the Launceston newspaper, the Cornwall Chronicle, reported that the annual cost of the treaty was £200.[7] This was not a trifling sum in 1835. For instance, in February 1835, the Crown sold ‘waste land’ (that is, land considered to be bush) in New South Wales at a cost of between five shillings and £33 per acre.[8] Using the five shillings per acre price, the 500 000 acres of land purchased by Batman would have entailed a one-off payment of £8300 if it had been purchased from the Crown in 1835.

In today’s values, the yearly ‘tribute’ of £200 could vary from $A300 000 to $A68 million, depending on our choice of measurement.[9] The $A300 000 is calculated by comparing the average income needed to buy a commodity, while the $A68 million is derived from an understanding of economic share, which is the worth of a commodity at a particular time, divided by Gross Domestic Product. Another comparison is the sale of the 376 000-hectare Kalala Station near Daly Waters in the Northern Territory, which sold for $A58 million in 2019. (The Port Phillip claim was just over 20 000 hectares.)[10] Batman and the Port Phillip Association clearly believed the expense was warranted by the profits they could generate.

At Batman’s and the Association’s urging, the British and colonial governments rejected the basis of the treaty. But Batman and the Association continued to pay the tribute until 1838.[11] More than likely, the Batman Treaty, if it had been honoured, would not have been updated to modern prices. Looking at comparable agreements for land that the British signed with Asian rulers, such as the 10 000 Spanish dollars annually that the East India Company paid to the Sultan of Kedah for Penang in 1791, or the 300 Spanish dollars paid to the Sultan of Sulu for North Borneo (now Sabah) in 1878, the Malaysian government (as the successor government) still pays annual fees of 10 000 Malaysian Ringgit (RM) – about $A3300 – and RM5300 ($A1700) for the two territories.

We could go back, however, to the spirit of Batman’s treaty, that of a relationship, in which the settlers are bonded to the Kulin. What does that word ‘relationship’ mean? Explaining the relationship to his peers in Van Diemen’s Land, Batman wrote he had promised,

to protect them [the Kulin] in every way, to employ them, the same as my own natives, and also to clothe and feed them, and I also proposed to pay them an annual Tribute in necessaries as compensation for the enjoyment of the Land … live amongst them … [and pay a] reservation of the annual tribute to those who are real owners of the soil.[12]

Possible site of the Batman Treaty, Merri Creek, Northcote (Port Phillip Pioneers Group)

As a successor community to Batman, we have not lived up to that promise of his. If Batman and the Association believed that the equivalent of $68 million per year was a just cost for a treaty – before taking into account, any accumulated historical debt of colonial abuse — what is the cost of a just treaty now?

*Gareth Knapman is a Research Fellow in the Centre for Heritage and Museum Studies within the College of Arts and Sciences (CASS), Australian National University, Canberra. In 2021 he published an article ‘Settler colonialism and usurping Malay sovereignty in Singapore’ in the Journal of Southeast Asian Studies (vol. 52, no. 3). For Honest History, he reviewed Armenia, Australia and the Great War, by Vicken Babkenian and Peter Stanley, and wrote an article about the work of Bain Attwood on ‘terra nullius’.

[1]Paul Sakkal & Jack Latimore, ‘A “Black Parliament”? Victorian government discusses Indigenous voice’, The Age, 23 October 2021.

[2] Bain Attwood, Empire and the Making of Native Title: Sovereignty, Property and Indigenous People, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2020; Bain Attwood, Possession: Batman’s Treaty and the Matter of History, Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2009; James Boyce, 1835: The Founding of Melbourne and the Conquest of Australia, Black Inc., Melbourne, 2011; Alastair Campbell, John Batman and the Aborigines, Kibble Books, Melbourne, 1987; AGL Shaw, History of the Port Phillip District: Victoria before Separation, Melbourne University Publishing, Melbourne, 2013 (first published 1996).

[3] For example: ‘Miscellaneous News’, Hobart Town Courier, 26 June 1835, p. 4; ‘The Tasmanian Penn.: Launceston, V.D. Land, Saturday, June 13, 1835’, Cornwall Chronicle, 13 June 1835, p. 2.

[4] ‘The Batman deed Melbourne 1835 June 6’, State Library of Victoria MS 13484.

[5] Attwood, Possession, p. 44; Boyce, pp. 67-8; Shaw, pp. 46-7.

[6] The Batman deed.

[7] ‘The Tasmanian Penn.’

[8] ‘Domestic intelligence: recent sales of Crown Land’, The Colonist (Sydney), 19 February 1835, p. 4.

[9] Diane Hutchinson & Florian Ploeckl, ‘Five ways to compute the relative value of Australian amounts, 1828 to the present’, Measuring Worth.com, 2022.

[10] Kristy O’Brien, ‘For many, the dream of owning a NT cattle station is becoming increasingly harder to achieve’, ABC News, 17 October 2020.

[11] Boyce, pp. 70-1.

[12] John Batman, Report to Governor Arthur, 25 June 1835, republished, James Bonwick (ed). Port Phillip Settlement, Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington, London, 1883, pp. 204-5.