‘Keeping up with the Anzac centenary: have we passed “Peak Anzac”? Honest History, 13 April 2016

The PHA seminar of 5 April

The Professional Historians Association (Victoria) held a seminar on 5 April ‘reflecting on the Anzac centenary and memorialisation’.

Twelve months into the centenary of World War I it is timely to reflect on what this enormous investment in resources, money and scholarship has done for the practice of history. A panel of practitioners will reflect on what has worked and what we still have time to address/redress for the rest of the centenary period. How have centenary initiatives furthered our understanding of this conflict? Is there a disconnect between academic discussion about military history and the community’s connection to Anzac commemoration? What role does commemoration play in people’s lives?

Deborah Tout-Smith (Museum Victoria)

Deborah Tout-Smith (Museum Victoria)

Two of the speakers were Carolyn Holbrook of Monash University (and Honest History committee member) and Deborah Tout-Smith of Museum Victoria. Dr Holbrook summarises themes in her award-winning Anzac: The Unauthorised Biography and notes points made by Anna Clark in her recent book, Private Lives, Public History. She argues that ‘Anzac has become so powerful that it feels personal, even when it’s not’ and that academic historians need to recognise this.

How do academic historians, armed with evidence and analysis, compete with the emotional power of Anzac? For starters, we need to recognise Anzac commemoration for what it is – an emotional ritual wrapped inside an historical event.

We need to understand that logical arguments are not the equal of emotional attachments. We need to strike at people’s hearts rather than their heads, because that is where arguments are won and lost. We need to use suggestion and gentle persuasion, always based upon the most rigorous evidence. We need to present our ideas within a readable narrative, rather than dry, jargon-riddled prose. These are massive challenges for the academy, but if we don’t take them up, then we risk being irrelevant.

Ms Tout-Smith discusses the World War I: Love & Sorrow exhibition, which she curated. (The exhibition was reviewed by Michael McKernan.) She argues that we need to be ‘more complete and open in our depictions of war’. She notes Professor Jay Winter’s insistence that depictions of weapons of war should be accompanied by evidence of what such weapons do to people.

I’ve become very conscious of what’s missing from depictions of war, particularly in leading institutions such as the Australian War Memorial’s new World War I galleries. There are still almost no dead, few maimed (although a little display acknowledges the facial wounds treated at Sidcup). There are no grotesque body parts, although some were “sampled” and are still preserved as specimens in public collections in Australia. There are no bone-collectors, no killing fields. But – what’s war about, if not this?

For me, the most powerful part of the AWM’s World War I exhibition is a small, dark space at the end where they acknowledge mourning, post-war struggles to cope with wounds and memories, and long-term impacts. If only there was more like it.

Ms Tout-Smith also noted that Love & Sorrow eschews references to nation-building, avoids quasi-religious language and the euphemisms ‘sacrifice’ and ‘fall’, and does not often use the word ‘Anzac’ or depict Gallipoli, or even give prominence to ‘mateship’. The exhibition tries to show both the strengths and the flaws of the people it portrays.

With war, we have to resist the temptation, I think, to make something positive out of it, to suggest that a nation is built, an honourable sacrifice is made, medical advances were remarkable, families make do, society holds together, we all move on. In fact, none of these things come close to making war justifiable … I hope we can contribute to breaking down the blanket of civility, respectability and comfort that is wrapped around the act of war.

Earlier events; future possibilities

The Victorian evening followed seminars in October (Brisbane) and November (Hobart). The Hobart meeting was notable for its breadth and conciseness. It took soundings on today’s commemoration, including its commercial aspects, the tendency to slip into the inappropriate term ‘celebration’, the Great War and its direct impacts (particularly in generating xenophobia and division on the home front) and its longer-term effects, the wartime role of Indigenous Australians, as well as patriotism and support for the war and early commemorative efforts.

The Brisbane seminar, by contrast, produced over six hours of video with speakers including Kate Aubusson, James Brown, Martin Crotty, Carolyn Holbrook and Francis Leach. One question they confronted was, ‘As we move further into the four year commemoration period it would be easy to think that we have reached “peak Anzac”‘. This seminar is a long haul without a transcript but it is worth the effort.

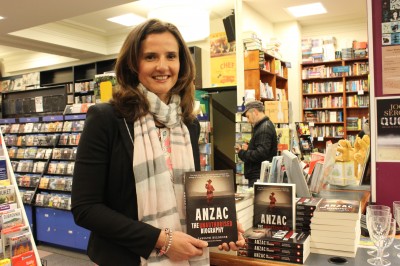

Carolyn Holbrook (Monash University)

Carolyn Holbrook (Monash University)

There was also a seminar in the ‘Defining Moments’ series at the National Museum of Australia on 29 October last. The speakers were Carolyn Holbrook again, Brad Manera from the Anzac Memorial in Sydney, and Peter Stanley from UNSW Canberra and president of Honest History. While the Museum has not yet posted the video, those who attended heard the speakers vigorously consider these questions:

Are people tired of remembering events from 100 years ago? Is Gallipoli still as symbolically potent as it was 100 years ago? What is the value of Australia’s largest and most public of commemorations since the Centenary of Federation?

These events are symptomatic of the soundings being taken in these centenary years. Beyond the seminar circuit, though, the jury is out about whether we have passed ‘Peak Anzac’. It will be interesting to see how many people attend Anzac services this year, in Canberra, the state capitals, Turkey and France.

A century ago, enthusiasm for war flagged as the months passed. Something similar seems to have occurred in 2015-16: the term ‘commemoration fatigue’ started to be used as early as March 2015; the number of visitors to Lone Pine in August 2015 was well below expectations; this year we have seen an attempt to wind back the intensity of commemoration at Anzac on 24-25 April; the current list of commemorative events is much shorter than the one attached to the original report to the then Australian government on how Australia should commemorate the centenary; the ‘story’ about commemoration 2016 seems to be more about terrorism keeping pilgrims away than reverence bringing them.

What next, a century on? Watch this space.

13 April 2016

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.