‘Honest History highlights reel: Nick Dyrenfurth’s Mateship: A Very Australian History’, Honest History, 11 October 2016 updated

Update 22 October 2021: A survey on mateship throws up some interesting results.

***

Nick Dyrenfurth’s book Mateship: A Very Australian History, was published by Scribe in 2015. This highlights reel picks out some key paragraphs. We used the Kindle version of the book. Our earlier post on the book with links to some reviews and other material. This highlights reel by agreement with the author. The book can be purchased here.

Mateship and egalitarianism

Lane’s venture [New Australia 1893] aimed to ‘practically demonstrate that men and women can live together in perfect peace and contentment if absolute equality and absolute mateship is taken as the basis of the movement’. (Kindle Locations 55-57).

But what does mateship actually mean? Most simply, it describes the bonds of loyalty and equality, and feelings of solidarity and fraternity that Australians, usually men, are typically alleged to exhibit. (Kindle Locations 78-79).

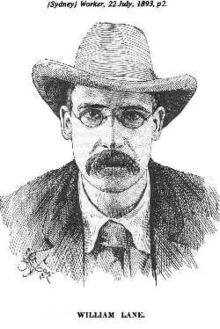

A left-wing or working-class ideal of mateship voiced by the likes of William Lane has long-existed; however, most Australian citizens would more likely associate mateship with wartime service — in particular, the Anzac tradition forged on the shores of faraway Gallipoli during April 1915. Public commentary on the Anzacs almost always contains a reference to Australians’ proclivity to all things matey. (Kindle Locations 80-83).

A left-wing or working-class ideal of mateship voiced by the likes of William Lane has long-existed; however, most Australian citizens would more likely associate mateship with wartime service — in particular, the Anzac tradition forged on the shores of faraway Gallipoli during April 1915. Public commentary on the Anzacs almost always contains a reference to Australians’ proclivity to all things matey. (Kindle Locations 80-83).

For better or worse, mateship is part of our cultural DNA. In a nation supposedly hostile towards spiritual or ideological dogma, mateship has acted the part of a de facto religion. Symbolically speaking, mateship is said to embody our secular egalitarian predilections. (Kindle Locations 91-92).

Russel Ward and bushmen and Tom Inglis Moore

Why did mateship become Australia’s pre-eminent national ideal? In his landmark cultural history, The Australian Legend (1958), Russel Ward argued that the origins of Australia’s national identity were to be found in the anti-authoritarian and egalitarian ethos of convict society. This rather vulgar collectivist philosophy was also exhibited by the labouring men who roamed Australia’s outback during the mid-19th century. (Kindle Locations 97-100).

As Tom Inglis Moore noted in 1965, Australian mateship simply ‘offers a new variation on one of the most ancient of themes — the friendship between man and man, keyed to equality, with loyalty as a refrain. It is a theme running through the literature of many lands and times.’ (Kindle Locations 114-115).

Rhetorical egalitarianism was further refined by emancipists and Australian-born currency lads, men prone to assert that Australia, as ‘the prisoners’ country’, ironically belonged to them rather than wealthy immigrants or ‘new chums’. The strength of this belief meant Australian egalitarianism henceforth became akin to an upside-down phenomenon, lamented by some critics as Australia’s tall-poppy syndrome. In journalist Craig McGregor’s words, wealthy citizens have always felt ‘under some pressure to be accepted by ordinary working Australians rather than the other way round’. Even today, billionaire mining magnates hailing from establishment families cloak themselves in the rhetorical garb of mateship, as much as they do the hi-vis vests of ordinary workers. (Kindle Locations 329-334).

It was no coincidence that, around this time [mid 19th century], the European population came to see itself as distinctively and proudly Australian. Henceforth, a brash egalitarianism stood at the heart of Australian identity. According to Russel Ward, that ethos grew most clearly among the semi-nomadic band of bush workers engaged in the burgeoning pastoral industry — drovers, shepherds, shearers, bullock drivers, stockmen, boundary riders, station hands, and assorted others. (Kindle Locations 346-349).

Ward’s bush creed of egalitarianism brushes reality aside, imagining mateship as the vehicle that carried the solidarity of the convict era into the tough labouring environment that was the lot of most bush workers. (Kindle Locations 355-357).

Gold

Henceforth, wrote Manning Clark, the ‘radicals and cultural chauvinists, all later-day believers in the uniqueness of Homo Australiensis, were fond of saying that the gold decade strengthened those two great articles in the creed of the bushman — equality and mateship.’ (Kindle Locations 519-521).

In the countless accounts of goldfields life that subsequently emerged, diggers were portrayed as romantic heroes who treasured democracy, equality, and, of course, mateship. None were more famously heralded than those men who defied the Victorian authorities during the December 1854 Eureka Stockade. (Kindle Locations 553-555).

William Lane (Wikipedia)

William Lane (Wikipedia)

Federation era

Yet some in the land were still considered less equal than others. Another significant act of the new federal parliament was the bipartisan policy of White Australia, which closed the doors to non-white immigrants, and repatriated Melanesian labourers. Likewise, Indigenous Australians were excluded from the benefits of citizenship. (Kindle Locations 1112-1114).

Great War including Bean and Lawson

As Charles Bean wrote before the outbreak of World War I, the miners of outback Australia voted Labor not because they had anything in particular to get from a Labor government, ‘but chiefly because it is a necessity to the miner to be what he considers loyal to his mates elsewhere’: You cannot talk about that sort of loyalty — the more it is bragged about the shallower it becomes. But one may just say this, that although the Australian will never be an effusive ‘imperialist’ or, probably, favourable to any hard and fast parliamentary constitution binding his country to the Motherland, still, if ever a certain ancient country, the old friend and protector of a younger land, finds herself in difficulties, there is in the younger land, existing in quite unsuspected quarters, a thousand times deeper and more effective than the more showy protestations which sometimes appropriate the title of ‘imperialism’, the quality of sticking — whatever may come and whatever may be the end of it — to an old mate. (Kindle Locations 1283-1291)

Mateship was quickly linked with male war service; ‘mate’ became synonymous with the soldier shorthands for friend, ‘cobber’ and ‘digger’. Bill Gammage, in his study of soldiers who served in the AIF, concluded that his subjects believed ‘mateship was a particular Australian virtue, a creed, almost a religion’. (Kindle Locations 1336-1338).

The wartime environment led many a conservative Australian to convert to the creed of mateship. And yet there’s a sense in which Anzac mateship complemented the freedom-fighting male heroism of the unionist bush legend of the 1890s, which itself drew on the spirit of the gold rush– era diggers. Ironically, this merging of traditions sat awkwardly with the fact that the Anzacs were a largely urban force. (Kindle Locations 1346-1348).

Henry Lawson’s 1915 poem ‘A Mate Can Do No Wrong’ insisted that Anzac mateship originated from Australia’s bush unions:

We learnt the creed at Hungerford, We learnt the creed at Bourke; We learnt it in the good times And learnt it out of work. We learnt it by the harbour-side And on the billabong: No matter what a mate may do, A mate can do no wrong!

Digger mates at the pyramids, 1914 (11 btnwags)

Digger mates at the pyramids, 1914 (11 btnwags)

Lawson’s ‘Song of the Dardanelles’ severely criticised those critics who had doubted the spirit of the native-born: The wireless tells and the cable tells How our boys behaved by the Dardanelles. Some thought in their hearts ‘will our boys make good?’ We knew them of old and we knew they would! Knew they would — Knew they would; We were mates of old and we knew they would … They’ll win for the South as we knew they would. (Kindle Locations 1353-1370).

[S]oldiers didn’t generally mount the pulpit preaching military mateship; rather, this task fell to self-appointed custodians of Anzac such as the official war correspondents Charles Bean and Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett. (Kindle Locations 1374-1375).

‘The typical Australian’, wrote Bean in The Story of Anzac, ‘was seldom religious in the sense in which the word was generally used. So far as he held a prevailing creed, it was a romantic one inherited from the gold-miner and the bushman, of which the chief article was that a man should at all times and at any cost stand by his mate.’ (Kindle Locations 1383-1385).

Post Great War

Over the course of the 1930s, labour-movement types vigorously sought to reclaim the egalitarian dimensions of mateship. Henry Boote claimed that the Depression had exposed the conservative ‘capitalist class’ for what they were — cynical exploiters of the Anzacs, ‘wallow[ ing] in cant and humbug’:

Look at these hypocrites, and listen to them, at patriotic functions. They speak of the soldiers with pumped-up tears in their eyes and mechanical emotion in their voices. On Anzac Day they dilate with an inflated eloquence upon the sacred duty we owe to those who fought for their country. And even while they do so returned soldiers in their midst are suffering more cruelly than they did in the worst days of the war, and the capitalist class hold out no hand to help them. (Kindle Locations 1732-1738).

Curtin

Curtin argued that this harnessing of the Anzac creed produced an equality of sacrifice not achieved in the Great War. ‘Business interests [are] submitting with good grace to iron control to drastic elimination of profits. Our great labour unions are accepting the suspension of rights and privileges which have been sacred for two generations … It is now “work or fight” for everyone in Australia.’ In other words, Labor-style mateship had won the day. (Kindle Locations 1862-1865).

Manning Clark

In [Manning] Clark’s view, mateship was both a romantic distortion of Australian history and emblematic of its uglier elements. Clark outlined these flaws in his 1954 essay, ‘Rewriting Australian History’. ‘The idea of Australia as a country with a great radical tradition inspired by the ideal of mateship, and as a laboratory or social experiment, should … be revised’, Clark asserted. Mocking the idea that democracy in Australia was born at Eureka, Clark alleged that ‘Mateship was very reactionary in its application to all outsiders, particularly non-Whites’. And where in the matey radical-nationalist story, he asked, was recognition of the nation-building role of the urban middle class, or the importance of religion? ‘The rewriting of Australian history’, Clark intoned, ‘will not come from the radicals of this generation because they are tethered to an erstwhile great but now excessively rigid creed’. (Kindle Locations 2163-2169).

Anzac revival from 1980s

Mateship reached its peak during this era in the early-to-mid-1980s. The Anzac myth was re-mined to establish a particular version of Australian national identity that centred around independent, anti-authoritarian men. This trend owed much to Patsy Adam-Smith’s book The Anzacs, which viewed the Great War as ‘the blood sacrifice of a nation’ — but the appearance of Peter Weir’s film Gallipoli (written by David Williamson) towered over all. (Kindle Locations 2389-2392).

Hawke

At Gallipoli in 1990, Hawke delivered a speech on the 75th anniversary of the landings. He lauded mateship as the Australian people’s ‘self-recognition of their dependence upon one another’, and noted that the men at Gallipoli had been drawn from every walk of life and different backgrounds before being ‘cast upon these hostile shores, 12,000 miles from home’. Hawke argued that ‘there lay the genesis of the Anzac tradition’. It was a simple but deep commitment to one another, each to his fellow Australian … It is that commitment, now as much as ever — now, with all the vast changes occurring in our nation, more than ever — it is that commitment to Australia, which defines, and alone defines, what is to be an Australian. The commitment is all.’ On his return to Australia, Hawke again pointed to the centrality of mateship to the national story: what defined the Anzacs was their ‘sense of mateship — in a word … sheer Australianness’. Hawke’s message was clear: we were all multicultural mates now. (Kindle Locations 2478-2487).

Howard

In a 1995 headland speech, Howard claimed that, under Keating, ‘the great egalitarian innocence, that egalitarian spirit … the birthright of most Australians only a short time ago, had significantly disappeared … [I]t will be his political epitaph that the Labor man from Bankstown did … betray the battlers of Australian society.’ (Kindle Locations 2607-2610).

In a 1995 headland speech, Howard claimed that, under Keating, ‘the great egalitarian innocence, that egalitarian spirit … the birthright of most Australians only a short time ago, had significantly disappeared … [I]t will be his political epitaph that the Labor man from Bankstown did … betray the battlers of Australian society.’ (Kindle Locations 2607-2610).

Modern mates (milkbarmag)

Howard interpreted his victory as one for his own true believers. As he claimed on the night of his re-election, ‘I want to dedicate my government to the maintenance of traditional Australian values. And they include those great values of mateship and egalitarianism.’ (Kindle Locations 2681-2683).

Speaking at a media conference following the release of the proposed [constitutional] preamble, Howard stressed that mateship had a ‘hallowed place in the Australian lexicon’, defining it as ‘the spirit of helping people in adversity’. Howard’s mateship was, as always, bedevilled by contradiction. If mateship was a product of Australia’s egalitarian DNA, so too was the tall-poppy syndrome. (Kindle Locations 2694-2697).

Military men recently

Australian troops stationed in Afghanistan from 2001 onwards were lauded for carrying on the proud traditions of Anzac. That conflict’s second Australian Victoria Cross winner, corporal Ben Roberts-Smith, reportedly said it was mateship that allowed him to brave a storm of gunfire to take out a Taliban machine-gun post that was firing on his squad. Reflecting on 100 years of army tradition, the Interfet commander, general Peter Cosgrove, asserted that the army embodied the best of Australia’s values: ‘A fair go, mateship, teamwork, a bit of self-sacrifice and volunteerism — the army is the essence of volunteerism.’ (Kindle Locations 2747-2752).

Mateship and egalitarianism summed up

This historian [Dyrenfurth] must also make a choice. I like mateship. I admire the mateship of ordinary Australians — male and female — especially in the workings of unionism and the humble rhythm of community life. I admire the mateship of the kind we glimpsed at Gallipoli, on the Western Front, at Changi, and on the Thai–Burma Railway. Mateship speaks not only to my intellectual concerns, but also the egalitarian values I think make for a good Australian life: solidarity, mutuality, and a humane form of patriotism. (Kindle Locations 2953-2956).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.