‘“A material triumph and an aesthetic calamity”: the work of Australian architect Robin Boyd’, Honest History, 11 October 2016

‘A material triumph and an aesthetic calamity’ was how architect and cultural critic Robin Boyd summed up our domestic buildings in his Australia’s Home, published fifty years ago this month.[1] Home ownership, allied to the motor car and suburban sprawl, was the foundation to the Menzies years. The prime minister campaigned on ‘homes spiritual, homes temporal’. In 1952, the percentage of Australians who owned or were paying off their own homes stood at 54; by 1962, it had grown to 68. ‘Australia is the small house’. Boyd acknowledged. ‘Ownership of one in a fenced allotment is as inevitable and unquestionable a goal of the average Australian as marriage.’

Robin Boyd (Text Publishing)

Robin Boyd (Text Publishing)

Hence, to criticise ‘Emoh Ruo’ was like being against motherhood. [2] Boyd’s book was thus courageous, the more so in an era when Melbourne society had led his very right-wing uncle, the novelist Martin Boyd, to conclude that ‘anything with which they are unfamiliar must be Communist’. Robin Boyd recalled that his generation had been made to feel ‘subversive’ for even living in cities, let alone writing about how they should be improved. Their ‘elders and betters’ considered the young to be ‘frivolous, perhaps cowardly, certainly contemptible’ for not being ‘out there smashing down the bush with one’s own bare fists’. To be citified was to be sissified.

Equally suspect was Boyd’s call for an architecture that was as alert to European and US innovations as it was to Australian conditions. At that time, people who had never been outside Australia talked fondly of England as ‘home’. To criticise both senses of home put Boyd in double jeopardy.

Robin led the way in establishing ‘Boyd’ as a brand name for culture. Nine months after the appearance of Australia’s Home, Uncle Martin contributed to family legend with the first volume in his Langton Quartet, The Cardboard Crown, which the Age did not review. The notion of a Boyd cultural dynasty did not exist in 1952, though the family had been respected among a circle of artists. Robin’s father, Penleigh, had been a painter before being killed in an automobile smash in 1923, when Robin was four years old. His widow and two sons moved into a Toorak apartment for the next four years, giving Robin a remarkable childhood for an Australian. In 1941, he and his bride rented a Roy Grounds flat in Armadale. These experiences helped him to see such alternative housing as acceptable, when 85 percent of Australians were in unshared dwellings.

On being articled to a reactionary architectural firm in 1935, he helped form a Students Association, editing its magazine, which handed out ‘blots’ and ‘bouquets’ to new buildings. He avoided a libel suit by publishing an apology – in Gothic script.

Australia’s Home was remarkable simply for being a serious book about Australia. In those days, we were lucky if one such was published in a year. No less striking was that Boyd retold the story of European settlement from a single aspect, and that his theme was neither sheep, the labour movement nor war – the three topics for most learned writing about this country. Geoffrey Blainey took heart from Australia’s Home, glimpsing the possibility of writing a history of how, rather than what, thereby celebrating the progress of technology instead of chronicling parliamentary politics.

Even at full stretch, Boyd was an evangelist, though better researched than other popularisers. If his insights relied on intuitive leaps, those hunches were grounded in a lifetime of looking. Boyd wrote in his spare time, without photocopiers and before research assistants. The gaps in his knowledge have given academics grounds for superiority though none has matched his reach or readership.

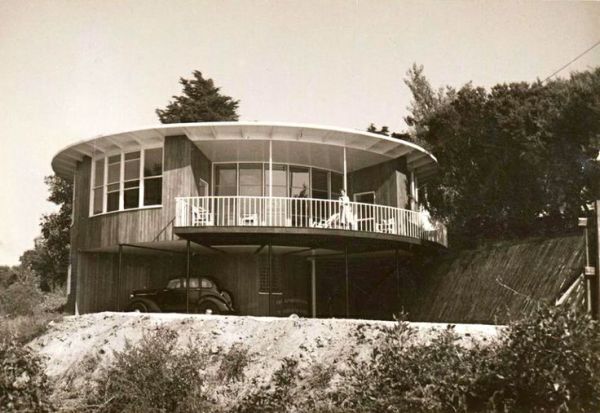

Roy Grounds house, 1953 (Misfits’ Architecture)

Roy Grounds house, 1953 (Misfits’ Architecture)

Good manners and personal charm spread to his views about design and distinguished his prose, marked by elegance and wit which flowed effortlessly throughout his life. Boyd’s manner and methods enlivened his chapter on how ‘Insects, Children, Animals’ had interacted with domestic design. Dogs were put outside. ‘The cat’s life, on the other hand, changed little or not at all from England to Australia. The cat saw to that.’

Robin Boyd gained an international reputation for his ideas, and did so without becoming an expatriate. In 1951, he made the first of numerous overseas sojourns but never uprooted. He was not without honour in his own country. Rather he was without profit, especially in his final days. To cure a protracted infection, barber surgeons removed his teeth. He died three days later, aged 52, on 16 October 1971.

Despite Boyd’s condemnation of an ‘aesthetic calamity’, Australia’s Home was mostly an account of how the ‘material triumph’ had been wrought. Boyd wrote about architects and construction firms as heroes or villains, but not in detail about the craftsmen, tradesmen or labourers.

Nor did he focus for long on the home from the viewpoint of its principal working occupant, the housewife and mother, few of whom then had paid jobs outside. He sounded more concerned for the look of suburbs than for their social fabric, paying scant attention to campaigns for slum renewal. Hence, he would welcome the Housing Commission towers when they went up around Melbourne in the early 1960s.

Between 1947 and 1954, Boyd directed the Small Homes Service for the Institute of Architects, with a weekly advice column in the Age. Architects provided plans which the self-builder could get in a booklet of twenty-four designs for sixpence, or as two sets of complete drawings for £5.

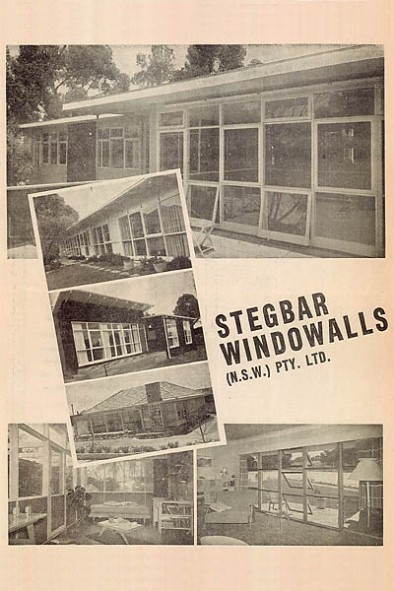

Boyd’s intention was not to give his fellow ex-Diggers and their wives what they wanted. He redrafted many of the patterns away from asymmetrical (‘Waterfall’) fronts and towards Windowalls from the Stegbar company, an example of the prefabrication in which he never lost hope. On the inside, he encouraged the removal of the walls between dining room and lounge, and then between the dining room and the kitchen. Rooms were being equalised as the kitchen became central and bathrooms decorated, making each more expensive to fit out than the living room. The refrigerator displaced the pianola as the pinnacle of civilised living.

Boyd’s tastes were elitist in as much as he did not accept that the jerry builder, any more than the advertiser, should have the last word on the good life. He commended the do-it-yourself home builder after the war for doing finer work than the speck firms. In explicating Australian architecture, Boyd held to the Functionalist precept of ‘a stark white flush box, flat-roofed, and slit by a few random windows’. He also retained a fondness for the minor revolution in domestic building that he had encountered in his youth, confirmed by his work with Roy Grounds.

Australia’s Home wove thematic chapters around an account of eleven successive styles, from Georgian Primitive in the 1810s, through Queen Anne at the turn of the 20th century, to L-shapes by the late 1940s. Boyd disparaged ‘Queen Anne’ style for its ornamentation which offended against the white box of Modernism. ‘Queen Anne’ also epitomised the national addiction to borrowing from England in defiance of building for the environment. In 1969, Bernard Smith would rename ‘Queen Anne’ as ‘Federation’, while architectural historians found in it many of the qualities of local fitness that Boyd valued.

Stegbar Windowall advertising, c. 1958 (Secretagent)

Stegbar Windowall advertising, c. 1958 (Secretagent)

Writing in the early 1950s, Boyd had perceived no sign of the Featurism that would be the target of his sequel, The Australian Ugliness. Even the gee-gaws dripping from ‘Queen Anne’ had not aspired to be a style. At most, he noted the contemporary ‘idea of featuring a door in a different colour’.

In 1960, Boyd recorded a worsening of the ‘aesthetic calamity’ in The Australian Ugliness. No previous book title about Australia had been so confrontational. In 1964, Donald Horne would limit himself to the irony of ‘The Lucky Country’ for a society mismanaged ‘by second-rate people who share its luck’. The usual approach was optimistic, summoning up a vision splendid or a utopian dream. Boyd adapted that latter term for his most ferocious attack – The Great, Great Australian Dream, published posthumously in 1972. In 1958, John Kenneth Galbraith had exposed the Affluent Society for its private splendours and public squalor. Boyd’s point was that private affluence was equally squalid, ‘a prey to thoughtless habits, snobberies and fickle sentiment’.

Reaction against the depression, war-time rationing and post-war shortages spawned a madness of colour. In the inner cities, owners of terraces painted their walls in a rainbow of Mediterranean primaries before picking out the ‘cast-iron trimmings in a new feature colour’. The housing boom of the 1950s brought changes in techniques and materials, to design and décor. That ‘proud and prosperous’ decade began with the ‘Wild Colonial Boy selling used cars’ and then careered downhill as Surfers Paradise and the Barrier Reef resorts mimicked Miami Beach. British Australia became what Boyd branded ‘Austerica’.

The Australian Ugliness was two books. One strand continued Boyd’s story of architecture in Australia, extending his reflections on all architecture as a ‘puzzle’ – to use the title of his 1965 volume. The other part was a barrage against ‘Featurism’. Among its earliest manifestations had been in 1950 as plants on park benches in Prahran were repainted in alternating red, blue, green and yellow. This innovation invaded domestic gardens as pergola beams flowered in different pastels.

Boyd identified Featurism as more than

a decorative technique, it starts in concepts and extends upward through the parts of the numerous trimmings. It may be defined as the subordination of the essential whole and the accentuation of selected separate features. The Featurist is not prepared to consider the simple proposition that no object which is true to its own nature needs cosmetics.

Elsewhere, he saw Featurism as only ‘skin deep’. His ready phrase-making contributed to this want of precision.

Boyd found ‘Featurism’ easier to describe than define, as in this depiction of a suburban house with

the living room thrust forward as a feature of the façade, a wide picture window as a feature of the projecting wall, a pretty statuette as a feature in the picture window, a feature wall of vertical boards inside the featured living-room, a wrought-iron bracket holding a pink ceramic wall vase as a feature of the feature wall, a nice red flower as a feature in the vase.

Featurism differed from Bavarian Baroque, with its cream-cake layering of gilt and curlicues, because those excesses remained true to their inspiration, whereas Featurism had no consistency. Featurism was not the kitsch that New York critic Clement Greenberg had excoriated in 1939. Many of the items used as Features were kitsch, but it was their juxtaposition that created Featurism.

Wilson Hall, University of Melbourne (UniMelbadventures)

Wilson Hall, University of Melbourne (UniMelbadventures)

Nor did Featurism establish its own style. It could appear in Georgian or Functionalist setting. As an instance of the latter, the crowning jewel of Australian Featurism was Wilson Hall at the University of Melbourne, which opened in 1956. Its designers had elevated ‘features into the major emotional role’, jettisoning every element essential to modern architecture in order to secure popular acclaim. The sculptured mural above the stage was a mammoth piece of costume jewelry to vanquish the ‘frightening honesty of the blank wall’. Hence, the bright idea of a local councillor and the supineness of the city’s leading architects were of a piece.

Paint and plastic supplied the media for a do-it-yourself Featurism built on colour, and more colours. The value of paint production increased fivefold in the decade to 1956. Manufacturers expanded their paint charts from six to sixty hues, advising hardware stores: ‘Don’t sell paint, sell colour’. Boyd recognised that ‘Multi-colouring ensured the opening of a profitable number of partly-required tins’. Women’s magazines sold faith in paint; the family that paints together, sticks together.

The other factor was plastic. From the late 1930s, the chemical giants could make plastics with an even spread of colour, unlike the marbled effects associated with Bakelite. By the early Fifties a simpler and cheaper method produced practically all known colours. ‘Plastics are Paint and Paint is Plastics’, proclaimed the hardware industry. Kitchen utensils were cheap enough to throw out for a quick colour change. ‘Pretty Polly’ became sales talk for Polystyrene. Laminex made its first sheets of decorative board in 1946 to revolutionise furniture trade, even before doubling its colour range in 1955.

In trying to deduce why Featurism was more rampant in Australia than in the other booming economies, Boyd fell back on the immigrants’ hatred of the landscape, the settlers’ need to block out its dead heart and to escape its vastness. ‘The greater and fiercer the natural background, the prettier and pettier the artificial foreground.’ He himself enjoyed Australia’s natural barrenness more than its built environments, though he had a soft spot for the coherence that galvanised iron roofs gave to Alice Springs.

Laminex table with chairs (Origeon)

Laminex table with chairs (Origeon)

Boyd concentrated his fusillade against domestic architecture because office blocks were only getting underway, though they provided horrors enough. He favoured the brutalism of rough concrete finishes as an antidote to Featurism. Indeed, cityscapes were blighted by allowing anyone to build anything anywhere. ‘A modernistic folly in multi-colored brickwork may sit next door to a prim Georgian mansionette on one side and a sensitive work of architectural exploration the other’, he bemoaned. Allans new music store in 1956 was clean-lined but its position by the Block Arcade turned ‘the heart of Collins Street’ into a Featurist shocker.

Boyd wanted civic coordination but not the kind that had given the leafy suburbs their orderliness in the 1920s when Berger Paints advised home-builders ‘to avoid the choice of colours that will conflict with neighboring homes’. Boyd would mock this approach as the Cream Australia Policy.

In reporting the victory that Harry Seidler had had over the building regulations of the Warringah Shire Council in 1949 as a triumph for contemporary architecture, Boyd never paused to ask whether this defeat for conformity had opened the sluice gates to Featurism. Similarly, he approved of a pyramidal house in Kew, because it ‘declared war on conservatism’, excusing its ‘harlequin of red or yellow’ on the grounds that that Feature was ‘an inherent part of the total design’.

This sophism was not his self-defence in 1971 when he stuck a green bubble dome on top of a fish-shop in Toorak Rd. That adornment, he replied, was fun, not Featurist. To be Featurist each triangular section would have been a different colour beneath iridescent sea creatures. The Fishbowl provided an opportunity for Yarraside to get its own back on Boyd for having shown that Malvern and Moonee Ponds were sisters under their Featurist skin.

Australians preferred to equate ‘ugliness’ with the outrage of overhead wires and street signs. That tangle could be blamed on the government. Boyd’s ‘ugliness’ was not only inside the home, it was in the heart. Those who welcomed Boyd’s assault were in thrall to the Scandinavian, for example, Arzberg and Arabia crockery. Others shared his fondness for everything that’s Japanese, oblivious to the vulgarity of boom-time Japan.

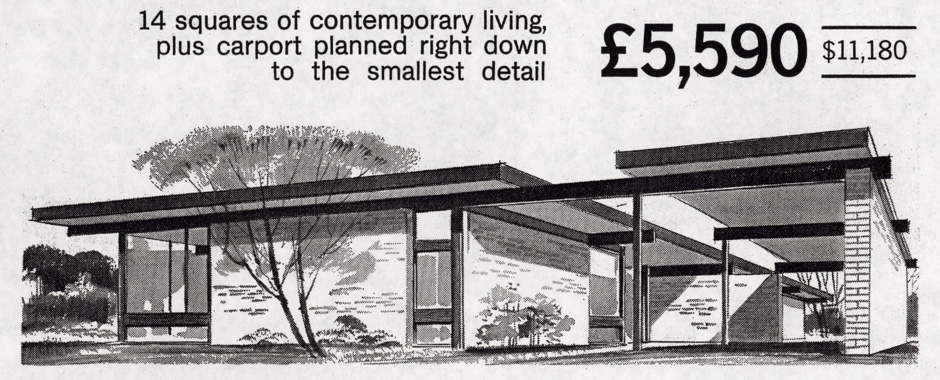

Pettit & Sevitt marketing, c. 1968 (Canberra House)

Pettit & Sevitt marketing, c. 1968 (Canberra House)

In an epilogue to a 1968 reprint of Australia’s Home, Boyd tried to sound optimistic: ‘The violent primary coloured “contemporary” was giving way to a debased Japanese character.’ The improvement around Sydney had begun in 1962 when the project builders Pettit & Sevitt offered white-painted brick walls, rugged textures and brown stained timbers. Before long, these elements achieved a Featurism of stones, bricks, rocks and wood grains, with Colour Field canvases to block out that white wall.

Also in that epilogue, Boyd hoped ‘the Australian ideal of a five-roomed detached villa for every family will recede further during the remaining years of the century’. The five-roomed villa has indeed disappeared. In its place is the five-bedroomed mansion. Australia is no longer the small house. Monstrosities abound on clear-felled hilltops and along waterways, natural or built. Australians with spare cash are more likely to renovate than invest. He rightly foresaw that the detached house ‘will be threatened by more flats, perhaps a revival of terraces, by cluster housing and other multiple dwelling types yet to be invented’. Despite inner-city refits and suburban in-fills, the sprawl advances on Bacchus Marsh.

Boyd concluded The Australian Ugliness with the declaration that Featurism had had its beginning ‘with fear of reality, denial of the need for every day environment to reflect the heart of the human problem, satisfaction with veneer and cosmetic effects. It ends in betrayal of the element of love and a chill near the root of national self-respect.’

While slipping loose from English taste, Australians had thrown themselves into constructing ‘Austerica’. Boyd alleged that most Australian brains were trading in second-hand ideas. ‘I would rather a first-hand Australian failure than another second-hand success.’ He hoped that the revolt against Australia’s being a sponge of society would come no later than the early 1980s. He did not see that it was burgeoning in 1967, to burst forth with plays, films and books throughout the 1970s.

In his 1967 Boyer Lectures, ambiguously titled Artificial Australia, Boyd spoke of what he called his impatient love for Australia, a love ‘that keeps the rebel here’, but a love that provokes a passion ‘to shake Australia till its false teeth rattle’. Like Xavier Herbert and Patrick White, Robin Boyd lurched into despair about Australia because his love for its possibilities was so intense. In The Great, Great Australian Dream, he rejected the cliché that Australians were still searching for our national identity. Far from it – our identity comes at us with ‘a protruding beer belly and a receding brain’.

The targets of Boyd’s critique overlapped with those of Barry Humphries. Edna’s dress sense epitomised Featurism. The difference was that Boyd became angry because Australians would not change quickly enough. Humphries turned nasty as Sandy Stone’s Cream Australia policy fell beneath the plastic fifties. One voiced frustrated hope, the other resentful nostalgia.

Featherston house, designed by Robin Boyd (Domain)

Featherston house, designed by Robin Boyd (Domain)

Notes

[1] This article was originally published in 2002. It appears on Humphrey McQueen’s Surplus Value website.

[2] ‘Emoh Ruo’ is ‘Our Home’ spelt backwards. An example of a 1950s house name. See also ‘Dun Roamin’ and various combinations of the names of husband and wife occupants e.g. ‘Ronjoanne’. HH

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.