‘Review note: Penleigh Boyd’s Salvage – sketching and writing on the Western Front’, Honest History, 7 July 2015

Theodore Penleigh Boyd (1890-1923) was a landscape artist and member of the multi-talented Boyd family. The Wikipedia entry is also useful.

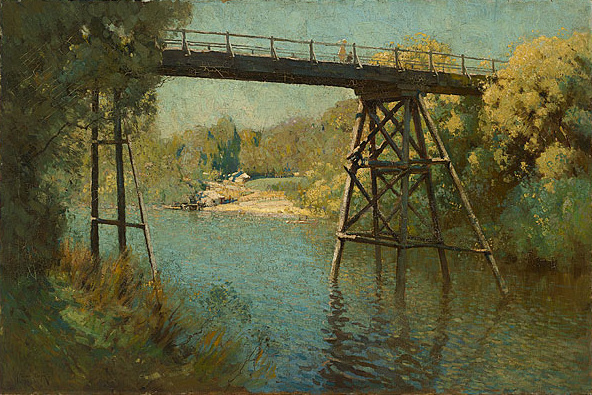

Bridge and wattle at Warrandyte, Penleigh Boyd, oil on canvas, 1914 (Wikimedia Commons)

Bridge and wattle at Warrandyte, Penleigh Boyd, oil on canvas, 1914 (Wikimedia Commons)

Penleigh Boyd served in France from 1915 and was gassed at Ypres in 1917, suffering permanent physical and psychological damage. While his promising career as a landscape painter was cut short by his death in a car accident, he also left Salvage, a ‘souvenir’ of his service, published in London in 1918. Less than 50 pages long, it is a set of pen pictures and sketches done in 1917. The writing is spare and honest, the sketches well-observed and economical. (There is a problem with the link but cutting and pasting this should work: https://digital.slv.vic.gov.au/view/action/singleViewer.do?dvs=1435744847865~946&locale=en_US&metadata_object_ratio=10&show_metadata=true&VIEWER_URL=/view/action/singleViewer.do?&preferred_usage_type=VIEW_MAIN&DELIVERY_RULE_ID=10&frameId=1&usePid1=true&usePid2=true .)

A dugout has been generally my studio [Boyd wrote] and I drew chiefly to occupy my time and distract my thoughts, during the long hours of rumbling bombardment overhead, hoping at the same time, that perhaps in the future the sketches might be found interesting by those who are not lucky, or unlucky, enough to have witnessed some of the incidents of the Great War.

Highlights among the writing are ‘The despatch rider’ and ‘Church ruins at Ypres’, for their descriptions of the landscape, ‘German trenches after an advance’ (‘a rigid arm or leg sticking out of the earth, or a body lying half submerged in the stagnant water of a shell hole, dyed by the gases in unwholesome shades of red or green’) for its matter-of-fact description of horror, and ‘Supper time’ and ‘The communication trench’ which present the incongruous domesticity of trench life. The sketches titled ‘The Menin Road’, ‘After the rain’, and ‘Among the poppies’ are particularly affecting.

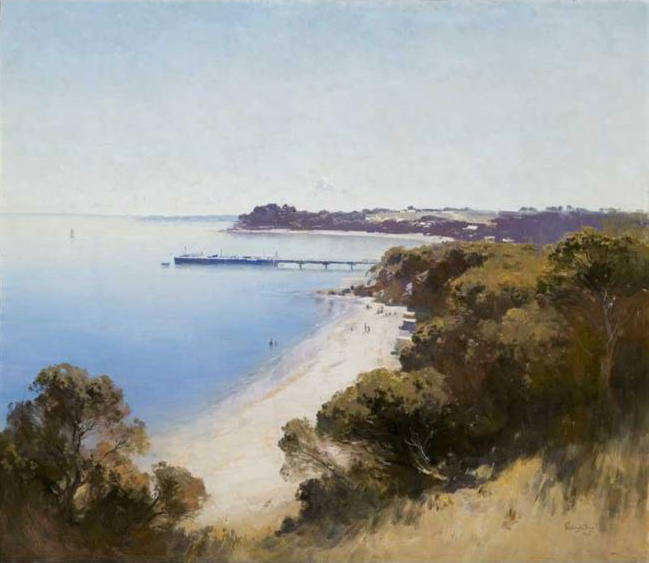

Portsea, 1921, Penleigh Boyd, oil on canvas (Wikimedia Commons)

Portsea, 1921, Penleigh Boyd, oil on canvas (Wikimedia Commons)

Yet in a period (today) when Aussie puffery is particularly prevalent, it is Boyd’s note on ‘The Anzac’ which deserves quoting at length. It shows the comfortable ambivalence that ‘Australian Britons’ felt at the time about their status and encourages us to exercise care about making rash assumptions based on ‘presentism’ – the inclination to project modern views and standards onto our forebears.

Much has been written of the Australian soldier. He is generally credited with exceptional bravery and dash in battle, and a greater or less amount of wild lawlessness while on leave or in barracks. The truth of the matter is that he varies but little from his English brothers, either in dash or lawlessness, and he is the first and most anxious to assure you of this fact. His fighting spirit is fine and deserves the recognition that is so generously meted out, but there should be no distinction drawn between this and the magnificent dogged determination manifested by all the British troops. As to the freedom of his behaviour whilst in England or elsewhere, please remember that he is away from his home and all tender associations, and for that reason may show to some disadvantage compared with the Englishman who is returning to wife or mother. Is it not excusable under the circumstances if in his search for diversion he should tend towards riotousness? In the line he displays the same qualities of stolid pluck, kindliness and generous sympathy for a “cobber” in distress that distinguishes the British race throughout the world.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.