We first posted this in 2016 and have reposted it since but it is very apt again, speaking as it does to how characteristics are nurtured and passed on, mentors and governments brown-nosed and seduced – and sometimes perhaps controlled the latter.

Sir Keith (Arthur) Murdoch (1885-1952) seems to have been a piece of work (though not without redeeming features), fairly much cloned into (Keith) Rupert, the soon to be Emeritus Mogul. (Keith) Rupert’s mother, Dame Elisabeth Murdoch, was nicer and a philanthropist.

What can we expect from Lachlan (Keith) Murdoch and how much does it matter? (Keith) Rupert will be cracking the whip for a while yet, even if it falls on deaf ears. Dame Elisabeth lived to 103.

See also this post from former (early 1970s) Rupert senior manager, John Menadue. Not a fan now.

***

Lord Northcliffe (egged on by Keith Murdoch) talks up the Anzacs after Pozieres: Honest History document

‘“These young giants from the furthest corner of the earth”: Lord Northcliffe (egged on by Keith Murdoch) talks up the Anzacs after Pozières: Honest History document’, Honest History, 30 August 2016

The document below is taken from The Sun (Sydney) for Sunday, 6 August 1916. Honest History’s Steve Flora tidied up the transcription in the National Library’s Trove scan. We have added the illustrations and the following brief scene-setter.

A martial triangle: Billy Hughes, Northcliffe and Keith Murdoch 1916

Lord Northcliffe (1865-1922, born Alfred Harmsworth) was the Rupert Murdoch of his day and not just because, like Murdoch, he owned The Times and sought to make and unmake governments. (Northcliffe is credited with helping ease Asquith out of the British prime ministership and Lloyd George into it in 1915-16.) Northcliffe also used his papers and his networks to argue for an aggressive approach to fighting the war against the Central Powers. Articles of his like the one below were brought together in At the War (1916) and Lord Northcliffe’s War Book (1917).

Lord Northcliffe (Wikipedia)

Lord Northcliffe (Wikipedia)

Though encouraging and sanitised reports from the front were pretty much the norm in 1916 in the cause of boosting the war effort, it is interesting that Northcliffe’s article was published in The Sun just a few days after Prime Minister Hughes returned from Britain and Europe, on the verge of committing to conscription. (It appeared just as the Battle of Pozières was concluding.)

In Britain in the first half of 1916 Hughes had worked closely with Keith Murdoch, father of Rupert. A biographer of Keith Murdoch describes him as Hughes’ ‘personal publicist, guide-to-the-British mind, fixer, speech writer and errand boy’. [Desmond Zwar, In Search of Keith Murdoch, (1980), p. 50] Murdoch oversaw the publication at this time of three books lionising Hughes for his approach to the war. [Tom Roberts, Before Rupert: Keith Murdoch and the Birth of a Dynasty (2015), chapter 3]

Northcliffe formed the third side of the triangle. (Apart from anything else Hughes, Murdoch and Northcliffe had in common, they were all keen golfers.) Keith Murdoch had been a journalist with The Sun and by 1916 was the London head of the United Cable Service, which distributed Northcliffe’s articles to Australia and elsewhere.

Murdoch had come to know Northcliffe in 1915 when Murdoch was trying to get publicity for his ‘Gallipoli letter’. He then worked with Northcliffe to boost Hughes as an important player in prosecuting the war in the vigorous directions that Northcliffe supported. ‘Much of Hughes’ dizzying profile [in elite London and in France in 1916]’, says Joan Beaumont, ‘was managed by Keith Murdoch, who was now based in the building of The Times and in league with its owner, Lord Northcliffe, and its editor, Geoffrey Dawson’. [Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War (2013), Kindle Location 3032-33]

Geoffrey Serle wrote of the Murdoch-Northcliffe connection ‘As early as 1916 Murdoch called him [Northcliffe] “as good a friend as I have ever had”, but he recognized that if he became an employee their relationship would inevitably be destroyed. Murdoch once wrote to Northcliffe as “My dear Chief … the Chief of All Journalists (of all ages)”.’ Serle added that Keith Murdoch modelled himself closely on Northcliffe. Given the strong filial links in the Murdoch dynasty, the Rupert Murdoch-Northcliffe comparison suggested above is not far-fetched.

Sir Keith Murdoch during World War I (Wikipedia)

Northcliffe went to Pozières at the urging of Keith Murdoch. ‘Foremost in Murdoch’s mind’, writes Peter Rees in his biography of Charles Bean, ‘was to present positive reports of Australian achievements on the Western Front. He persuaded Lord Northcliffe to visit Australian troops in France in 1916 and write about their achievements.’ [Bearing Witness (2015), Kindle Location 3616-18] It seems a reasonable hypothesis that Northcliffe’s rosy report of Australians in France – bronzed giants, cheerful, loyal and obedient, bloody but unbowed despite a tough time at Pozières – was then planted by Murdoch in The Sun and elsewhere not just to disseminate praise of the Anzacs but also to help Hughes prepare the ground for stepping up the war effort, probably through conscription, which Murdoch supported.

Like similar puff pieces from the front, Northcliffe’s may have placated some community misgivings about the war itself. (Apart from the article’s being featured in The Sun it seems to have appeared mainly in regional newspapers in Australia and New Zealand.) A few days before Northcliffe visited, Bean had also written a positive piece from Pozières for the Australian papers but changed his mind after seeing more of the effects of the battle. [Ross Coulthart, Charles Bean (2014), Kindle Locations 3270-90]

***

WITH BIRDWOOD AND THE ANZACS IN FRANCE

Bivouac Scenes and Trench Tales

OUR MEN RETURN FROM POZIERES

Specially Written for the Sun by Lord Northcliffe

LONDON, Saturday.

Lord Northcliffe has been spending a fortnight with the Australians in France, and has written some exclusive despatches for the United Service. He writes as follows:

Anzac Headquarters.

The high hopes of Australian peoples are centred round a bare room in one of the numberless French chateaus, where nowadays the air vibrates with the throbbing of the guns. In that small room, the principal furniture of which is the simplest possible bed, a telephone and a map marked with the latest moves on the battleline, is General Birdwood, the Idol of the Anzacs. Captain Chirnside received me at the gate, where stood guard two Australian giants, having before them their fluttering flag with the six stars. It was a muggy morning, reminding Captain Chirnside of an October in late shearing time. We passed through a hall where numbers of men of the clerical staff were busy at typewriting at the telephone— and so upstairs to General Birdwood’s room.

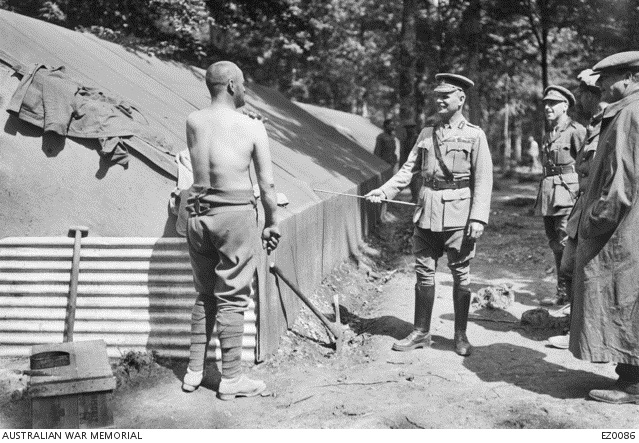

Birdwood, Northcliffe (flat cap) and soldiers, 28 July 1916 (AWM EZ0086)

Birdwood, Northcliffe (flat cap) and soldiers, 28 July 1916 (AWM EZ0086)

General Birdwood stands 5ft. 9in. in height. He has not an ounce of spare fat on him, and looks like a man in hard training. He has a strong but gentle voice, a firm mouth with a slight moustache, deep-set, pale-blue eyes, and a cropped head. He looks a fighter every inch of him. He has for 50 years been engaged in the business of war (most of his lifetime). He eats and drinks little, and is up and away at day-light in winter and before 6 o’clock in summer. He pushes his headquarters as near the front as possible, knows many of his boys, and calls them by their Christian names, and they believe in him as implicitly as he in them.

As Chief of Staff he has young White, a Queenslander, known throughout the British Army as quick of decision and able at once to grasp the minutest feature of any problem. With him, too, is Major Butler, the famous traveller, as Intelligence Officer, Col. Griffiths (of Victoria), and Major Smythe, D.S.O., of Christchurch, General Legge (Senior Australian Divisional Officer), and many other Imperial officers. General Birdwood, erect in a pale khaki coat, with some four rows of well-earned ribbons, cord breeches, and riding boots, is not the man to lose a moment. He was just off to meet the boys back for a rest from Pozieres.

Anzacs in Camp

They were camping in the Home Woods, to which we drove in his open car which flies the Australian flag. Some had already arrived. The sun, which had been absent for some days, came out at this moment. Never had I seen a more delightful sylvan scene than that presented by these battle-worn but merry soldiers, with their booty of German helmets, caps, and, here and there, German drums and field-glasses, riding and walking to their huts and tents.

Some were boiling tea and making dampers, or cooking beef in cookers extemporised from kerosene tins, or eating heartily after their long, long vigil in the heavily-shelled trenches at Pozieres. They instantly recognised General Birdwood. Most of them were from New South Wales, and had been engaged, most probably, in their hardest fight since Gallipoli. They had dug themselves in deeply on the other side of Pozieres, and had not left the trenches for days.

“My boys are good diggers,” remarked the General. “They dug deeply and quickly, and so cleanly that you could eat off the trench-floors at dinner-time.”

Northcliffe, CEW Bean, soldiers and kerosene tins, 30 July 1916 (AWM E00794)

Northcliffe, CEW Bean, soldiers and kerosene tins, 30 July 1916 (AWM E00794)

General Birdwood addressed his soldiers simply and truly, drawing first from one and then from another stories of the fierce fighting just experienced. Some were so tired that they had fallen asleep immediately they arrived, others were full of life and gaiety. As Captain Mackenzie, of the Salvation Army (known throughout the Peninsula and France as “Mac”), said, many were anxious to get back to the firing-line and show the Germans that if they were looking for more trouble they could have it. I looked with interest at these already hardened warriors, for whom death, wounds, and the German guns had no terrors.

Australian Discipline

A good deal has been said about Australian discipline. The Anglo-Australians amongst them assured me that when fighting their discipline is as rigid as the most adamantine commander could wish. They obey their officers implicitly from the moment serious business begins, and their relations with the Imperial officers are perfect.

The fact that young English schoolboys and the slightly older lads who man the aeroplanes had driven the spying Germans from the sky, rejoices the Anzacs. Gallipoli has made them excellent trench-fighters. I accompanied General Birdwood from one portion to another of the scattered forest scene. In some of the huts the men were all asleep. General Birdwood would on no account allow them to be disturbed. In other huts they were merry with mouth organs, flutes, and captured drums. General Birdwood peered in, and would not allow them to desist. Here and there they formed a temporary line and saluted. He has a simple speech for every group:

“You have suffered, but you’ve done splendidly, are you ready for more when the time comes?” he asks.

There always comes the great shout “Yes!”

In Single Combat

Many were the stories told. One was of a mere lad (for some are extremely young) who chased a huge German into the open, and finally settled the terrified Hun after a hand-to-hand bomb duel. Another tale was that of a German machine-gunner, who fired at the Anzacs until he had used up the whole of his cartridge-belt, when he threw his arms round the nearest Australian and cried, “Pardon, Kamerad!” All the time the men were talking the clashing and booming of the great guns were reminders of the proximity of the terrific struggle. Men came into the wood in a constant stream. Having seen their General, they went at once to wash, eat, and sleep.

10th Battalion memorial cross, Pozières, May 1917 (AWM E00493)

10th Battalion memorial cross, Pozières, May 1917 (AWM E00493)

General Birdwood had always one piece of parting advice to the boys. “Write home! Let your mothers know what you are doing, and how you are, for if you don’t she will write to me. I get dozens of letters every mail asking about sons.”

The sharp rattle of machine-guns high in the sky told of a prolonged fight. Afterwards, through the leaves, a German aeroplane was seen to fall. It was a raw spectacle, for the Hun is not often seen across our lines these days. I left this simple forest scene regretfully, but glad in heart that I had seen these lads.

Something was in preparation. General Birdwood took me into his car, and we passed more and more Anzacs on their way into and out of the battle. Some were asleep on top of highly-packed general service transport waggons. Some in German helmets were singing. All smiled affectionately as they saw the general, and saluted with a quick eyes right, or raising of the hand, while the mounted men dropped their hands sharply to the side. It was a long and interesting cavalcade on its way home from battle.

All were in good spirits despite their heavy losses. They had done well.

Passing through the mined towns and villages we reached a divisional headquarters, where, in a small house, some new movement requiring General Birdwood’s attention was being planned. It was a ruined building, with a mass of telephone wires pouring in at the windows. There was a busy click of typewriters, and the voices of men working in the heat in their shirt-sleeves.

Shell Reaches Headquarters

Hard by a great shell fell, wounding several men, and cruelly mutilating a young English officer, whom, during the evening, I saw being wheeled from the operating theatre at a neighboring hospital.

General Birdwood is one of those soldiers who believe it their duty to be in the firing-line whenever possible. His staff disagree, because two years acquaintance has so endeared him to them that they would feel lost without him. He has often been far too close to Pozieres for their happiness. They urged him not to go further, but he took me to the nearest field ambulance (No. 2), under Lieutenant-Colonel Horne. The slightly-wounded Australian at the gate, replying cheerily to the General, said: “Oh, we’re filling up nicely, General.”

Advanced Dressing Station, Middle Harbour, France, Arthur Streeton, 1918 (AWM ART93095)

Advanced Dressing Station, Middle Harbour, France, Arthur Streeton, 1918 (AWM ART93095)

As the ambulances arrived at the gate the stretchers were carried in in less time than it takes to write, Major Wright and Major Jolly (of Melbourne) classifying the cases, seeing that they were fed, and arranging those who were fit to get the anti-tetanus serum injected. This is done with great speed and care, and the letter marked on each forehead in indelible pencil, whereupon the cases are conveyed to the casualty clearing station, whence they go to one of the beautiful base hospitals, probably overlooking the Atlantic – hospitals which are the pride of the Empire.

We went thence to the first Australian field ambulance, under Col. Shaw, of Melbourne. Sir Anthony Bowlby, one of England’s greatest surgeons, was inspecting it. I spent the time talking to the wounded lads. Some were sleeping, others lying awake in pain, but most of them were ready for a joke, a chat, or a cigarette.

Boys Like France

“How do, you like France?” I asked a young Victorian.

“I like it fine,” he replied.

“They can teach us something in farming,” said another.

“There’s not an inch of land wasted. They work, wet or fine,” a young Bathhurst giant said. “The girls are all right, too.”

“Yes, I would like to take a couple back,” chipped in a wounded Adelaide boy.

I was duly shocked, but the compliment to France was sincere. It expressed admiration for the French, just as the French love the Australians for their kindness to children.

When not fighting they have delightful resting camps, well fitted with canteens and comforts for the men. Herein one finds all types, clerks, blacksmiths, men from the station and the farm. Many of the officers are of the same class, and so they understand each other and obey each other without question. They have exactly the same rations as the British, and draw only a portion of their handsome pay.

CEW Bean, John Masefield, Will Dyson and Alexis Aladin, Pozières battlefield, May 1917 (AWM E00509)

CEW Bean, John Masefield, Will Dyson and Alexis Aladin, Pozières battlefield, May 1917 (AWM E00509)

General Godley commands another portion of the line containing Australians and New Zealanders. Here the trenches, unlike those at Pozieres, are made behind breastworks of sandbags, and are very different to the Somme trenches, which are not unlike the deep excavations at Anzac. It is in General Godley’s part of the line that the young Australians are watching interestedly the wonderful French cultivation of all kinds of crops.

“We have had no lunch,” said a staff officer. “General Birdwood eats nothing and expects us to do likewise.”

The Cumbered Roads

We drove away from the wounded lads along the cumbered roads, past miles of waggons with the emblem of Australia, the rising sun, or the New Zealand fern upon them, to the chateau. During the ride General Birdwood told me something of Australia’s generosity to its forces, the promptness of the Australian Government in responding to his requests, and the great help given by the Australian Red Cross. These fine soldiers are making Australia’s history, building up the traditions of her future armies. There is hardly one of them who has not patriotism burnt into his soul – and burnt into his body, too, for many of them as a pledge have tattooed on their arms the Australian and Allied flags, with the words “Gallipoli, 1915,” underneath this device.

After a long drive through the dust I shared a simple meal (tea duly predominating) with the alert and agile chief and staff. As I drove away for many miles along the lines I could not but marvel at the turn in the world’s conditions which had brought these young giants from the furthest corner of the earth to shed their blood to aid the Powers which were gallantly fighting for the greatest cause in the world – freedom as opposed to tyranny.

Main street, Pozières town, December 1916 (AWM A05776/T. Yeomans)

Main street, Pozières town, December 1916 (AWM A05776/T. Yeomans)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.