The ‘Divided sunburnt country’ series

On 31 July 1916, Prime Minister WM Hughes returned to Australia (Fremantle) after six months in Britain and Europe, where he had raised Australia’s profile in Allied war councils. He spoke at the Melbourne Town Hall on 8 August. In the speech (one of a number he gave after his return) can be seen hints of where Hughes took Australia in the next few months, although crucial details were still to be settled.

WM Hughes and family with Neville Chamberlain and family, Birmingham, May 1916 (NLA PIC P880/3 LOC Portrait Drawers A21)

WM Hughes and family with Neville Chamberlain and family, Birmingham, May 1916 (NLA PIC P880/3 LOC Portrait Drawers A21)

At Spencer Street

‘We are proud of you’, the Victorian Premier, Sir Alexander Peacock, had said to the prime minister, as Hughes’ wife and young daughter, Helen, many dignitaries and 50 Anzacs milled around the prime ministerial train at Spencer Street station. Most members of the federal Labor Cabinet were present, along with a collection of Victorian politicians. A crowd of 5000 people thronged the footpath outside the station. Three cheers rang out, Mrs Hughes was presented with a sprig of wattle and a basket of flowers and the prime minister with a model of the cruiser Australia, also constructed with flowers.

He [the PM] seemed as light-hearted as if he were coming home from a holiday instead of returning to take up the threads of grave problems in a great crisis. He was genuinely touched by the warmth of the greeting he received from young and old, but the Prime Minister does not wear his heart on his sleeve. He concealed his emotion, and became all the more jocular …

Baby Helen, in the arms of her nurse, had been regarding the flurry around her with the utmost indifference, but she became interested when the photographers got to work, and looked femininely proud when, with a sprig of wattle in her hand, she was held high in the air by her father to be “taken” for the moving pictures.

The Prime Minister then spoke briefly to the group of Anzacs, praising their citizenship as much as their fighting qualities:

It is a great thing when it can be said of men drunk with glory and exalted by the passion of war, as it is said, and can be said with truth of the Australian soldier in England, that he is the very pattern of what a citizen should be. (Cheers) As to what the Australian soldier has done in war, I can say that the men who set that high standard at Gallipoli have done for us a great thing. Not only have they uplifted Australia in the eyes of the world, and carved for themselves a name that will be immortal, but they have set a standard for those that follow them, and the men now in France are following their example nobly and well. (Cheers.)

The Town Hall

The Prime Minister began his speech by saying that he firmly believed he had ‘the warm and hearty approval of nine out of every ten of the people of Australia’. He expected there would be the occasional discordant note but he was determined ‘to go on to the end’. He warned sternly against a ‘dishonourable’ or ‘premature’ peace. Throughout the Empire, ‘all men are thinking the same things and are putting aside those things which before the war they thought important in order that they may achieve victory at all cost’. Instead, ‘”we must dare all things and endure all things till the goal of victory and security is reached”. (Loud applause.) … We must resolve to sacrifice all things that we may be victorious.’

Hughes avoided directly raising the possibility of conscription but one of the warm-up speakers, Peacock, made a point of recalling that Hughes, before the war, had strongly supported compulsory military training for boys and ‘we were grateful for the seeds he sowed then’. The Defence minister, Senator Pearce, who favoured conscription, spoke of Hughes’ ‘triumphal progress’ since his return to Australia. Hughes, Pearce said, ‘might rest assured that, whatever sacrifices he might ask of the people in the future, he would have the Commonwealth behind him’. Loud cheers followed.

Conscription had been a live issue at least since the War Census of September 1915. Meetings pro- and anti-conscription had been held in a number of places in Australia in the days before Hughes returned to Australia. Anti-conscription meetings were being broken up by the police under the provisions of the War Precautions Act. Returned soldiers demonstrated in favour of conscription. The pro-conscription Universal Service League was holding regular lunchtime meetings in Martin Place, Sydney.

When Hughes returned to Australia, the Labour newspaper, The Worker, greeted him with the hopeful words ‘Welcome Home to the Cause of Anti-Conscription’, though some anti-conscription people were convinced that Hughes had been successfully duchessed by pro-war forces at home and abroad. In the early days of August, Labour councils in a number of states had passed resolutions against conscription.

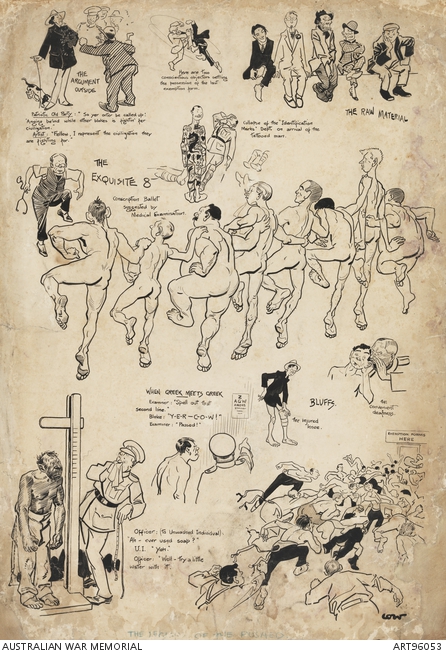

The legion of the pushed c. 1916 (AWM ART96053/David Low)

The legion of the pushed c. 1916 (AWM ART96053/David Low)

The watchers

‘During August, 1916 [wrote LC Jauncey 20 years later] the one question in Australia was “What will Mr. Hughes do?” He had been making speeches in different cities in the Commonwealth, but carefully refraining from committing himself to any set programme.’ In Adelaide, the day before Melbourne, he had hinted a referendum might be held, though the Adelaide paper, The Critic, referred to the ‘studied ambiguity’ of all Hughes’ speeches since his return to Australia.

Hughes’ biographer, LF Fitzhardinge, summed up the position:

Almost all his associates, including his defence minister (Sir) George Pearce pressed the need for conscription, and he was not fully aware of the strength of opposition within the trades unions and the Labor Party. He had returned half convinced of the need for compulsion and wholly determined to give the troops at the front whatever reinforcements they needed.

Donald Horne had a similar view:

Hughes had come back to Australia already knowing that he wanted to introduce conscription but he walked softly. Over the four weeks in which he was deciding he would go about it, he made loud speeches to patriotic audiences and said – nothing.*

The Australian Worker‘s editor, Henry Boote, was watching closely. Under the headline, ‘The old Hughes, or a new’, Boote had written on 3 August:

It is a curious circumstance, and a significant one, that while the capitalistic papers [like The Argus] are slobbering over William Hughes, and hailing him on his return from England as though he were a bright god stepping from a star, in the very same issues they are assailing with a poisonous malignity the Movement that brought him into being.

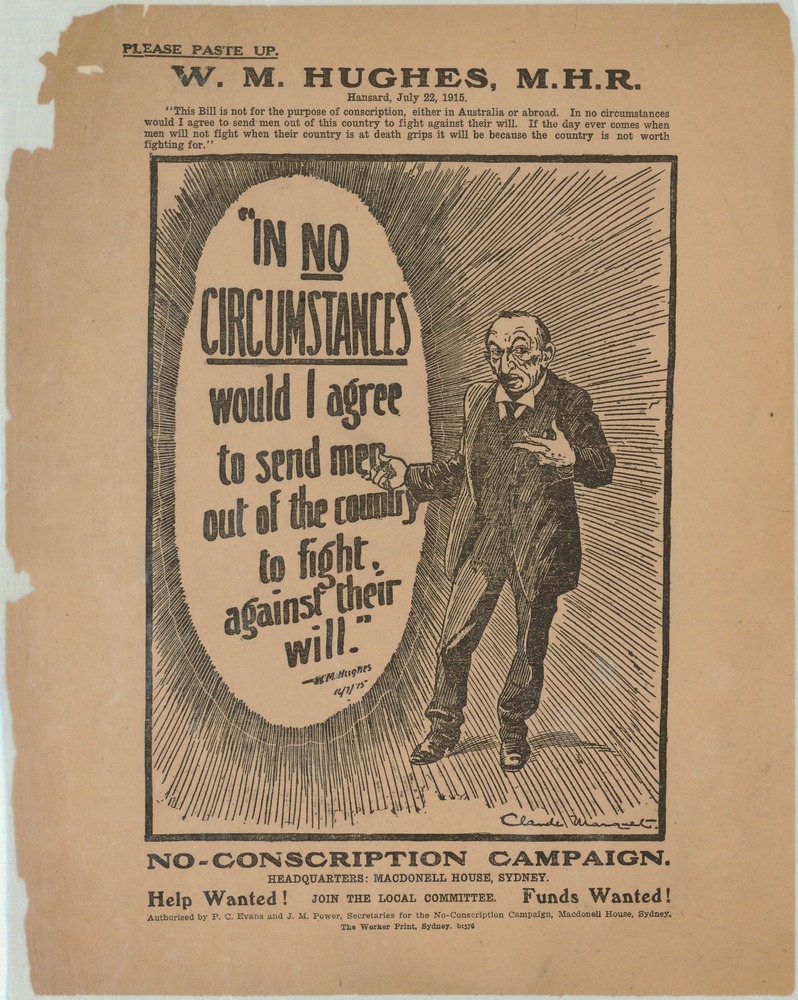

These interests knew they could not pervert the Labour movement, said Boote, but they reckoned they could seduce Hughes. Boote quoted Hughes in July 1915 denying any intention to conscript men to serve overseas and concluded: ‘We do not believe that the William Hughes of to-day intends to scab upon the William Hughes who gave that definite pledge to Australia only a few months ago’.

Others were on the case, as well. Hughes’ parliamentary colleague, WM Higgs, wrote to the prime minister on 12 August, saying that ‘Conscription will, in my opinion, split the political labor party into fragments’. In New South Wales, however, Premier WA Holman was strongly pro-conscription. Higgs and Holman represented what was becoming a deeply divided party and movement.

While Hughes may have been unsure of where he stood in relation to his party and the country, The Argus, speaking for the conservative forces, had no doubt, reporting on the rapturous applause of the Town Hall audience and averring that ‘Mr. Hughes never enjoyed greater popularity than he does at present’. To The Argus, conscription was the inevitable (and popular) implication of Hughes’ talk of the need for sacrifice; Hughes may not have been quite at that point but there were plenty of people pushing him towards it. As the prime minister’s car swept away up Collins Street, the packed crowd shouted, ‘Good boy, Billy Hughes’, and cheered lustily.

21 August 2016

* Donald Horne, The Little Digger: A Biography of Billy Hughes, Macmillan, Melbourne, 1983, p. 76. The other material here is taken mostly from the 9 August edition of the conservative Melbourne newspaper, The Argus, and from Joan Beaumont, Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2013, ch. 3, and LC Jauncey, The Story of Conscription in Australia, Macmillan, South Melbourne, 1968; first published 1935, ch. V.

Anti-conscription poster 1916, quoting Hughes 1915 (SLV Riley Collection/NLA/Claude Marquet)

Anti-conscription poster 1916, quoting Hughes 1915 (SLV Riley Collection/NLA/Claude Marquet)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.