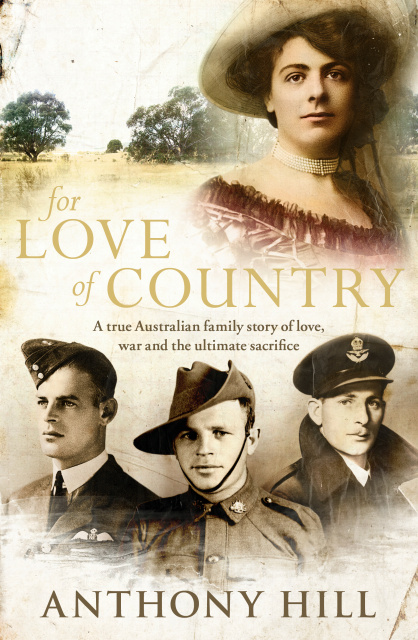

‘For love of country in war and peace’ (review of Anthony Hill), Honest History, 7 June 2016

Gentle Reader reviews Anthony Hill’s For Love of Country.

This book is described on the cover as ‘a true Australian family story of love, war and the ultimate sacrifice’ and the contents are exactly what the blurb says. The book is in three parts: World War I; the inter-war period in the Canberra area; World War II and afterwards. It is a deft combination of family story, local history and war memoir, well-written by the experienced, Canberra-based, Anthony Hill (author of The Story of Billy Young and a number of books for children and young adults).

Walter Eddison arrives in Australia just before World War I as an immigrant from England, newly married, though his wife, Marion, remains in England with the intention of emigrating, too. But war breaks out and Walter heads back to the Northern Hemisphere with the 56th Battalion, where he serves at Gallipoli, on the Western Front and in the Middle East. Whatever illusions he held about the glories of war service fall quickly away. Hill brings out this change particularly well. ‘This is a terrible war & I pray it will soon be over’, writes Walter to the mother of a dead comrade.

Walter Eddison arrives in Australia just before World War I as an immigrant from England, newly married, though his wife, Marion, remains in England with the intention of emigrating, too. But war breaks out and Walter heads back to the Northern Hemisphere with the 56th Battalion, where he serves at Gallipoli, on the Western Front and in the Middle East. Whatever illusions he held about the glories of war service fall quickly away. Hill brings out this change particularly well. ‘This is a terrible war & I pray it will soon be over’, writes Walter to the mother of a dead comrade.

Hill paints a picture of the awfulness of war, the terrible loss of life, the pointlessness. He makes no attempt to dress up something that should never be dressed up. He repeats a point that others have made – the experience was so awful that men could only speak of it to other men who had been through it, because only they could understand – but adds an additional, thought-provoking gloss: soldiers’ inability or unwillingness to talk protected their families from even a second-hand glimpse of war.

Except, one feels that the families must have wondered at their fathers’ and brothers’ moods and melancholy and, often, their violence. Still, the failure in so many families to pass on stories of horrors may have helped perpetuate the sanitised legacy of war, encapsulated in the platitudes about passing on instead ‘the torch of remembrance’ to new generations: don’t know, just remember. Such families are particularly susceptible to gloopy Anzackery.

After the Great War, the Eddisons, Walter and Marion, and soon three boys and three girls, struggle to make a go of a soldier settler block where Canberra’s Woden Valley suburbs sit today. They try different types of farming, they struggle in the Depression, they see neighbours walk off their blocks and they extend themselves to take up new leases, even though the costs are high, because the lease rates were set in good times. They see the commencement of the Australian War Memorial in Canberra in 1929, then the delays in building it as the economic slump hits. (The Memorial is finally opened in November 1941, with another war well under way.)

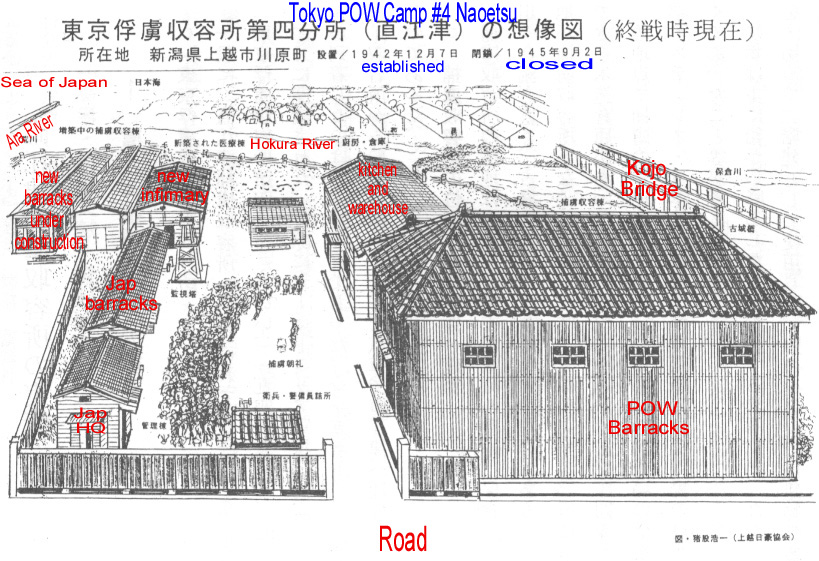

The Eddisons’ eldest son, Tom, is smitten by the flypast of Avro planes at the opening of Parliament House in 1927 and hatches a long-term plan to become a flyer. When war breaks out, he tries for the RAAF, misses out, makes it into RAF Bomber Command, is shot down over the Netherlands and it is some time before his family knows of his death. The second son, Jack, is turned down by his beloved, fudges his eyesight test, gets into the army, is captured in New Guinea, and dies in a prison camp in Japan. It is two years before his family knows his fate. Third son, Keith, starts off training others to fly in the RAAF but then is accepted for operations, despite a TB scar on a lung, and flies Beauforts. He is listed as ‘missing believed killed’ and his family never hears from him again.

In May 1943 Walter and Marion heard that Tom’s grave had been found in Holland. Keith died later in May and Jack died on 7 June. Three Eddison sons, three dead. The Eddison parents had clung to their property, despite difficulties, so they could pass the farm on to their sons. There was no hope of that now. The parents and daughters Diana, young Marion and Pamela, did their best to get on with their lives. Many years later, a park next to the Woden Cemetery (where Walter is buried), near the location of the family property ‘Yamba’, is named Eddison Park. It contains a skate park for children. Yamba Drive sweeps past, down towards Tuggeranong. On the other side of Canberra there is an Eddison Place.

Naoetsu POW camp (North China Marines)

Naoetsu POW camp (North China Marines)

After the war Walter and Marion travel overseas and visit Tom’s grave. The last surviving Eddison daughter, Pamela Yonge, helps Anthony Hill with material for the book. Among her papers is the poem written by a fellow soldier for the men who died with Jack Eddison in Naoetsu camp in Japan:

When days were gray, their tired yet steadfast eyes

Would turn to gleaming sands and rolling plains,

To wheat fields kissed by gentle southern rains,

And gum trees nodding under azure skies.

The armchair strategists and urgers, uniformed or elected, who weigh the odds for and against future military adventures should consider whether they are prepared to run the risk of such lines having to be recited over the victims of their new wars.

This book emphasises yet again the importance of individual and family stories as an antidote to the thoughtless mass-produced and mass-targeted hype that has characterised much of Australia’s commemoration in recent years. Hill’s book leaves us not with ‘a warm fuzzy feeling’ (as the commemoration industry seems to prefer) or surges of patriotic fervour, but with other feelings altogether.[1]

Gentle Reader is a Canberra lawyer.

[1] Bruce Scates writes in his World War One: A History in 100 Stories (2015) of a senior public servant saying that what the public wanted from the Anzac centenary was ‘a warm fuzzy feeling’, not stories of horror but ‘a positive nation-building narrative’.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.