‘Fighting against the tide?’ (review of Martin Woods on World War I maps), Honest History, 15 September 2016

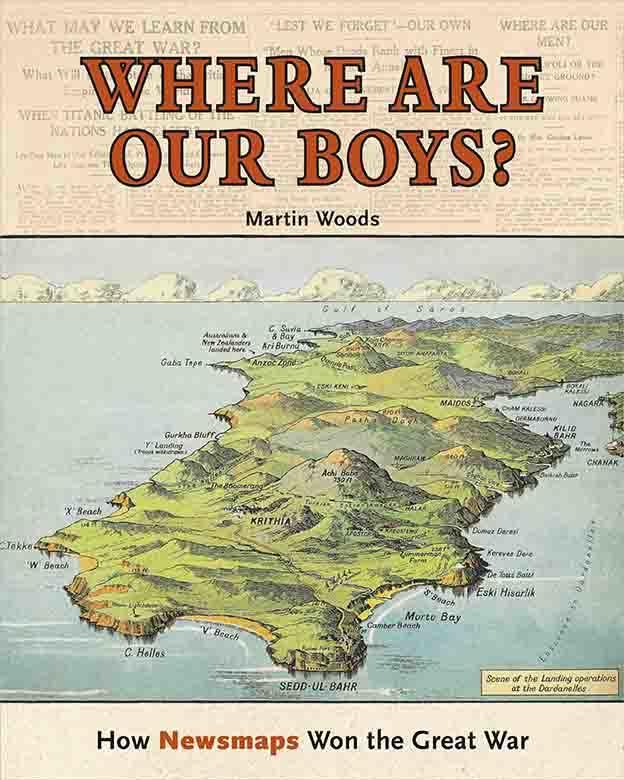

Peter Stanley reviews Martin Woods, Where are Our Boys? How Newsmaps Won the Great War

The National Library of Australia, uniquely now among national cultural institutions beleaguered by the affronts of federal governments intent on cutting their budgets and functions, continues to publish books based on the riches of its collections. The Library has a long and distinguished record of producing attractive and informative books of enduring value, and Where are Our Boys? continues that proud but possibly finite tradition. In publishing the book, the Library may well be fighting against the tide, just as the users of the maps in the book often felt they were.

Dr Martin Woods, the Library’s Curator of Maps, has selected a slew of colourful and revealing maps from the Library’s collections to demonstrate how Australians were informed about the progress of the fighting (or lack of it) in the Great War. Accompanying the images is a text that interprets the maps and explains how they were produced and for whom. The term ‘newsmap’ (new to this reviewer) makes sense and Dr Woods provides sufficient examples to establish that they represent a cartographic genus of their own.

Dr Martin Woods, the Library’s Curator of Maps, has selected a slew of colourful and revealing maps from the Library’s collections to demonstrate how Australians were informed about the progress of the fighting (or lack of it) in the Great War. Accompanying the images is a text that interprets the maps and explains how they were produced and for whom. The term ‘newsmap’ (new to this reviewer) makes sense and Dr Woods provides sufficient examples to establish that they represent a cartographic genus of their own.

One of the great strengths of this book is that it places the maps – reproduced in huge numbers in the newspapers of the day – in the context of the development of the use of maps to depict war (from the classical period on), the development of techniques of cartographic lithography, and the rise of the illustrated newspapers at the turn of the 19th century. The phenomenon of the ‘newsmap’ did not originate fully fledged in 1914 but governments’ need for vivid visual propaganda coincided with the emergence of a technology ably suited to informing and – all too often – misleading civilian readers.

So much were maps part of newspapers’ and readers’ experience of World War I that in 1916 the Bowen Independent, a Queensland newspaper, published a poem, ‘Following the war’, poking fun at those who earnestly tried to follow the war on half-a-dozen fronts:

The Terrible Turk joined the Hun fighting force,

Which meant maps of Turkey and Persia of course.

Then Italy, taking a hand in the game,

Obliged him to hang up a map of the same.

He had maps on four walls on the windows and door.

When the Balkans broke loose he had maps on the floor …

Where are Our Boys? traces how Australian and overseas newspapers incorporated maps into their ‘news’ reporting (actually largely propaganda). It shows how large maps were erected in the streets (outside newspaper offices) and shown even in picture theatres, which included animated maps in newsreel propaganda. Contrary to the bulk of Australian publications about the Great War today – they are excessively Australia-centric – at the time much of the Australian reporting sought to explain battles and campaigns on fronts in which no Australians served. Australian readers became familiar with the military geography of the Carpathians and Poland, of the Tyrol and the Caucasus, and not just the few square miles of Gallipoli or Flanders in which the Australian Imperial Force served.

Dr Woods shows how newspapers, the willing accomplices of official propagandists, printed diagrams, ‘artists’ impressions’ and cartoons to reinforce and drive home the messages that governments wished civilians to receive and heed. The entire collection reinforces how hard it must have been for civilians distant from the war (as Australians were) to form independent, much less objective, views. That Australians became so ‘war weary’ (as it was called) in 1918 that a bare majority withstood popular calls for a negotiated peace and even withdrawal from the war, shows how important this material was in maintaining commitment to the war and to the Hughes government.

My only quibble with Where are our Boys? is that it represents that newsmaps ‘won the Great War’, a claim only sustainable if it is understood as meaning that the propaganda value of civilian maps helped to deter awkward questions and mounting doubts that could have eroded morale and commitment – even more than years of mismanagement and defeat actually did. The sub-title, I surmise, was chosen not by the author, who surely knows better, but by the marketers, all-powerful now in publishing, who seek to sell books, regardless of the facts they purvey.

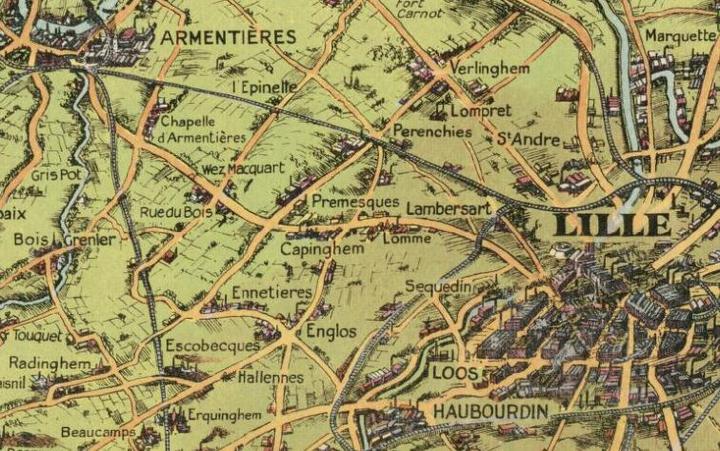

Detail of Daily Mail Bird’s Eye Map of the British Front 1916 (NLA 2179668)

Detail of Daily Mail Bird’s Eye Map of the British Front 1916 (NLA 2179668)

Martin Woods’s book is particularly relevant to those who share an interest in honest history because it demonstrates the lengths to which the authorities in the Great War went to disseminate a particular view of the conflict. A century ago, the events these maps depicted were still in contention, the subject not just of fighting overseas, but also of bitter contention at home. (This review is posted on the eve of the centenary of Prime Minister Hughes’ speech opening the pro-conscription case for what turned out to be the first of two unsuccessful referenda – or plebiscites, if you prefer.)

Though the guns of World War I fell silent nearly a century ago, the maps and graphics used to persuade civilians continue to do their work of misleading posterity: few of these maps can be trusted as sources. Only exposure and explanation can refute the assumptions and outright lies perpetrated a century ago and still liable to mislead. Governments, we infer, continue to behave with the same degree of amorality, expediency and outright dishonesty.

Given the Turnbull government’s unrestrained rapacity and Philistinism, whether the National Library can continue to publish books of this quality and value remains uncertain. I very much hope – and not just because I am an NLA Publishing author – that the Library can continue to contribute to historical understanding.

Professor Peter Stanley of the University of New South Wales Canberra is one of Australia’s foremost historians of the Great War and is President of Honest History.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.